By Jacqueline Gaybor and Wendy Harcourt

How can we reframe the current planetary crisis to find ways for decisive and life-changing collective action? The Amazon region of Ecuador, at the center of two crises –Covid-19 and a major oil spill–, but also home to a long history of indigenous resistance, offers some answers.

Navigating two crises

In Ecuador, the intensification of resource extraction and pollution, floods and weather disturbances have hit hardest marginalized populations. Indigenous peoples and people living in the Amazon have continuously suffered an enormous political and economic disadvantage when confronting extractive industries and allied state bodies. The vulnerability of the peoples and territory of the Ecuadorian Amazon region has been even more severely exposed during the Covid-19 lockdown period which began 16 March 2020.

On 7 April 2020, the Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System and the Heavy Crude Oil Pipeline, which transport Ecuador’s oil production, collapsed. The pipelines were built along the banks of the Coca River and the collapse resulted in the spillage of an enormous quantity of crude oil into its waters. The Coca river is a key artery in the regional Amazon system. It runs through three national parks that form one of the richest biodiverse areas on Earth, which has been historically preserved by the ways of life of the indigenous peoples who inhabit it.

The breakage of the pipelines impacted kilometers of rainforest riverways and tens of thousands of people. Indigenous populations living in surrounding areas are more at risk than non-indigenous populations because they rely on locally harvested food and water which can become contaminated. Indigenous peoples find it difficult to comply with lock down mobility restrictions since their subsistence depends on agriculture, hunting and fishing, which in turn have been severely impacted by the oil spills. The exposure to the virus due to the entry of technicians to repair the pipelines is another threat. These conditions have led the Confederation of indigenous nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) to warn of an impending genocide.

The Coca river valley before the erosion. Photo credit: Luisa Andrade

Despite the constitutional mandate to provide free and high-quality public healthcare for all citizens, the Ecuadorian national health system is fraught with problems. Health coverage in the Amazon region is precarious with a lack of medical facilities, doctors, and not enough Covid-19 tests and ventilators required to treat an outbreak. While elderly and people with comorbidities have been identified globally as most vulnerable from infection, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights identifies indigenous people as a risk group indeed, historically, pathogens have been one of the most powerful factors in decimating indigenous peoples in South America.

Depending on how an issue is framed, different responses can be expected, including why something is considered or not a problem, who is responsible, and what needs to be done about it. Environmental problems derived from the extraction of natural resources such as oil are mainly framed as localized problems. Thus, the burden is placed onto affected communities and local and national governments, while their global and systematic character is disowned. What we aim to say with this is that while there are directly responsible companies and governmental entities, their actions respond to a global system that is based and sustained on extractivism.

As the Covid-19 pandemic shows, it is only when a crisis is understood as part of a global web of relations derived from complex power dynamics, that we can imagine possibilities of globally coordinated and integrated efforts required for effective resolution. We are now living under global restrictions, which were once unimaginable, politically and economically. The rapid adaptation of quarantine and travel restrictions reveals that when the message of ‘human life is in danger’ is embraced, societies as a whole are able to perform in a short period of time the collective drastic changes required.

For Ecuadorian grassroots organizations and scholars, the Covid-19 pandemic is a reminder of our interconnectedness, our collective vulnerability, and therefore our mutual obligations with our planet. The pandemic is just one aspect of the human-made planetary crisis along with biodiversity loss and climate change. We are interested in how to reframe the current planetary crisis that encompasses increasingly visible global diseases in order to find ways for decisive and life-changing collective action. We ask these questions by looking at the Amazon region of Ecuador, which is bearing the brunt of two crises: Covid-19 and environmental destruction through a major oil spill.

“In the name of development”

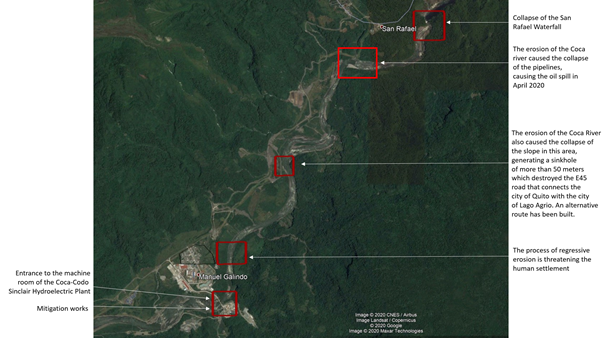

To understand the complexity of this human and ecological disaster, it is necessary to retrace some historical steps. On February 2, 2020, the San Rafael waterfall, the highest in Ecuador, collapsed. At that time, hydrologists warned that a phenomenon known as ‘regressive erosion’ could affect upstream infrastructure. On April 7, 2020 the Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources announced that the pipelines broke due to landslides that occurred in the San Rafael sector. Hydrologists associate the landslides with the construction and operation of the Coca-Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam (CCSHD).

Location of the most relevant events generated by the regressive erosion phenomenon of the Coca River. Infographic credit: Luisa Andrade

According to Carolina Bernal, PhD in Geomorphology and Hydrosedimentology, the CCSHD caused a serious imbalance in the transport of sediments and water through the river flow which produced a regressive erosion phenomenon which was responsible for causing sinkholes along the banks of the river. One of these sinkholes broke the oil pipelines. This risk had been mentioned in the earlier preliminary environmental impact study of the hydroelectric project.

CCSHD was inaugurated as part of Ecuador’s hydraulic mission during the presidency of Rafael Correa. The dam, like other hydroelectric projects carried out during his mandate, was politically legitimatized as “provider of clean energy and ‘good living’ for Ecuadorians and the world“. The rhetoric concerning the sustainable energy transition to renewable sources in the national energy matrix has been notably inconsistent with the dam’s high impacts on people and the environment.

The socio-environmental impacts associated with CCSHD and the oil spill were foreseen by the scientific community and civil society who were dismissed as “antidevelopmentalists” by Correa´s government. Some anticipated that the dam would a be major disruption of downstream sediment for the Napo River and would require extensive road-building and line construction in the primary forest. Others have questioned the true purpose of the dam, arguing that it was not about sustainable development for local people but rather to provide electricity to the oil fields.

One of several sinkholes caused by the regressive erosion of the Coca River. The sinkhole captured in this picture is close to the town of San Luis. Photo credit: Carlos Sanchez (August 2020)

Going beyond business as usual

Even if the world is still embroiled in the Covid-19 pandemic, the responses to this crisis have revealed stark unequal, racial, and geopolitical differences. The indigenous populations affected by the spill and the pandemic have denounced the abandonment of the state to attend to these two emergencies. The many commentators on the current changes in the social and economic constellation of the world are urging for the re-evaluation of our way of life and the possibility of a radical change. For Ecuadorian indigenous organizations and the environmental justice movement, the pandemic and the environmental crises call for a radical rethinking of economic growth and our current model of development.

Scholars like Maurie Cohen see Covid-19 as “a public health emergency and a real-time experiment in downsizing the consumer economy”. Accordingly, the outbreak could potentially contribute to a sustainable consumption transition. For Phoebe Everingham and Natasha Chassagne the crisis is an opportunity to challenge the atomized individualism that underlies overconsumption. For them, Buen Vivir, a central concept to Ecuador’s development planning, drawn from the historical experience of indigenous communities that have lived in harmony with nature, is a post-pandemic alternative for moving away from capitalist growth and re-imagining a new form of traveling and tourism.

We cannot return to ‘a normal’ that ignores the global environmental crisis which led to the inequitable and polluted societies that enabled the spread of Covid-19. The extractive vision of the living world is endangering humanity’s very existence. Is there space for a greater appreciation of the complexity of these intertwined crises? When will we see, as Bayo Akomalafe states, “Earth’s interconnected geological and political processes”?.

The extractive environmental activities that underpin capitalist development and a planetary-mass consumption culture are jeopardizing the very existence of humanity. Though environmental disasters have decimated and violated the rights of indigenous peoples in the Ecuadorian Amazon for years, they continue to resist. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, groups of Amazonian indigenous organizations promoted a model of autonomous governance of the Amazon region of Ecuador and Peru, through the “Sacred Basins Territories of Life” initiative.

The proposal has been developed by an alliance of indigenous peoples and nationalities of Ecuador and Peru to forge a new post-carbon, post-extractive model by leaving fossil fuels and mineral resources underground, retaining around 3.8 billion metric tons of carbon, to protect our planet and the well-being of future generations. The proposal would cover around 30 million hectares of land between Ecuador and Peru, home to almost 500,000 indigenous people of 20 different nationalities. Can these counter-hegemonic proposals which claim the interconnectivity of all species in this world be critically re-visited in the times of the pandemic?

Covid-19 brought the world to a halt. This ‘portal to a new era’, as Arundhati Roy proclaimed, offers us a chance to question deeply our social and economic relations. Perhaps this could be the moment in history where we also can finally reframe localized environmental disasters as global concerns, and act accordingly. This is the opportunity to re-think politically and socially how to transition to a different kind of development that acknowledges and changes the damaging way global lifestyles directly impact the indigenous peoples and natures of the world.

—

Jacqueline Gaybor is a Research Associate at the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University, in The Hague and lecturer at Erasmus University College in Rotterdam. Email: [email protected].

Wendy Harcourt is a Professor of Gender, Diversity and Sustainable Development at the International Institute of Social Studies of the Erasmus University, in The Hague. She is a member of the Editorial Collective of Undisciplined Environments. Email: [email protected].

—

Cover image: The Kichwa and Shuar indigenous nations launched a lawsuit against the state-owned oil company Petroecuador in April after the oil spills, to demand that the courts shut down the Trans-Ecuador and Heavy Crude pipelines. Source: Sophie Pinchetti/Amazon Frontlines.

One Comment