By António Carvalho and Irina Velicu

The current pandemic may be seen as another confirmation that industrialization, globalization, and the rapid consumption of all resources maximize the kinetic capacity of dangerous pathogens. The war machine against ‘virulent others’ – from nature’s rebels to pathogens – has never really taken a break. Ironically, such destruction of homes or habitats forces many of us now into a privileged ‘stay at home’, an emergent ontology of isolation which reinvents biopolitics and immunopolitics. What is the human political meaning of this ontology of isolation, a passive version of the ‘for the good of mankind’?

Taking the North by surprise, no longer confined to some distant South, a new virus suffocates the respiratory systems of thousands of people in Italy, Spain and the UK. A pandemic makes humanity plunge into the internal contradictions of its current health-political system. It becomes more clear that the pace of economic extraction virulently broke down ecosystems, releasing viral agents that threaten biological integrity. More and more scientists nowadays remind us not only that a pandemic was inevitable but that all the climate warnings of the last decade have exploded into something we can no longer control with the arrogance of negation. For those preoccupied nowadays with socio-ecological transformations and a more just and sustainable future society, the pervasiveness of trauma and disaster should not be disconnected from ongoing political projects based on fear, such as nuclear testing or virus-mitigation.

The State of Exception as an Ontology of Isolation

The extent to which the pandemic has induced (some) humans into a long-term hibernation – paralytic state of isolation, refuge or engaged fear in still inevitable activities such as medical caring or asparagus harvesting – will become a topic for many future debates. The many deaths, uncertainties and contradictions surrounding it increases its traumatic dimensions, pervading all circumstances of future life. This suspended or slow animation – as the ontological mode of “quarantines” – may be nothing more than the recognition that time is out of joint, due to the unimaginable speed of current socioeconomic systems.

The State of Exception is the biopolitical response to the pandemic – individuals are quarantined and societies are put in a state of suspended animation. Under this biopolitical Leviathan, what is now at stake is the perfect maintenance of hygiene and practices of self-regulation – we witness the emergence of hundreds of tutorials on “how to wash your hands” – civilizing sick and healthy bodies in an attempt to “contain” the pandemic. Individual confinement, hygiene, avoiding personal contact and technological surveillance, etc. are tropes that highlight that capitalist appropriation must now be redeemed by the affective choreographies of citizens-at-risk.

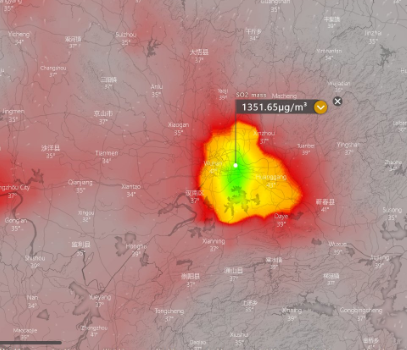

The highly contagious nature of the virus denies people the right to accompany their sick relatives or to embrace the bodies of their dead. Instead of being buried, bodies are cremated to avoid the spread of disease. Some internet users even suggested that there was an unusual release of sulfur dioxide gas from Wuhan, indicating that the atmosphere itself was being affected by this ritual of massive purification (this has been debunked –see here– but it’s an interesting aid to our theoretical imagination of the pandemic). While ICU patients are intubated and ventilators attempt to raise their oxygen levels, society at large falls under the guise of a hypnotic calmness, with biomedical interventions, prophylactic techniques, domestic spaces and technological paraphernalia grating citizens the right of “not-having-to-be-present in certain extreme states of one’s own psychophysical existence.” (Sloterdijk, 2013: 381). This means that, while we witness the failure of our biological support systems, the collapse of the economy, the suspension of all physical interaction, we retreat in domestic contemplation, a quasi-meditative state where we attempt to detach from the apocalypse outside, mindfully watching the world come to an end.

According to Snopes.com: “On Feb. 8, 2020, a well-shared Twitter thread claimed that “data” showed a massive increase in sulfur emissions over Wuhan, China. The thread further suggested that a likely explanation for this alleged observation was the cremation of bodies associated with the outbreak of the new coronavirus whose origin is in that region”. Source: Windy.com

These ontologies of isolation and confinement aim at suspending affective porosity, strengthening the boundaries among humans (and non-humans), erecting borders and building more (personal) walls in space and time. This disruption of international and bio-affective circulation renders the human collective into the perfect object of extractive capitalism. No longer allowed to leave home without State permit, vigilant bodies are immobilized in a state of traumatic shock, patiently waiting for the end of the war, having to trust the ability of governments to maintain their livelihood through subsidies and the massification of telework.

While life support systems and ventilators are mechanically introducing oxygen into dying human bodies, States of Exception do everything they can to save the status quo while the world falls apart. Biomedical and economic interventions are the dying breath of a society gasping for air after starting to realize that it is no longer possible to deal with “matter out of place”, excesses of virus and bacteria unleashed by the march of Capital. The ‘apocalypse forever’ feeling has been around us for long, ringing the bell for populists that there is opportunity in such consensual feelings of devastation and fear (Swyngendow 2010). The pandemic apocalypse legitimizes more technocratic depoliticized politics in fashion to stir Capital’s climates. Capitalist states facing the pandemic artificially inject trillions of dollars into the economy, trying to appease stock markets and corporations, in an attempt to keep business as usual.

Are current measures against COVID-19 “frantic, irrational”, making the State of Exception a “disproportionate response” (Agamben, 2020)? Historically, political reactions to epidemics exacerbate surveillance, isolation and social control, as plagues are “transmitted when bodies are mixed together” (Foucault, 1995: 197). Therefore, one may risk reifying these actions as the final victory of State Apparatuses, relying on fear to confine individuals to domestic and digital lives. But addressing the “molecularity of human relations” (Benvenuto, 2020) requires us to attend to the material qualities and processes of COVID-19 – its death rate, reproductive number, recalcitrance and devastating effects on the elderly and immunocompromised – thus examining how its politics of ontology matter. The eventful agency of COVID-19 is inevitably entwined with a set of material, discursive, technological and political paraphernalia, and the political should not be reduced to the apparent hegemony of the State.

Currently, our apocalyptic imaginary is supported by expressions such as the revenge of Gaia, planetary boundaries and tipping points -the perfect apolitical reasons justifying more technological and biomedical fixes (Swyngedouw and Ernstson, 2018). But this is not the time to fall into the old trap of critical humanism but to reinvent our theoretical imagination and ontological solidarities; we must delve into the new im-possible worlds brought forward by the virus, articulations of human bodies, pathogens and technological and material devices that are still to be collectively renegotiated. The pandemic, among other crisis, should force us to think in deadlocks, go back and forth to our own presuppositions, truths or identities.

This funeral in Romania, in the traditional style of Roma people, with music and tens of participants, is shamed for disrespecting the orders for public health: “We deserve our destiny!”. Source: Cancan.ro 2020

Caring Mantras in Isolation?

Slowing down and refraining from accelerated habitats destruction could have been the caring mantra of last decades at least, rather than the state of emergencies, deficiencies and panic – as if we could suddenly erase the great war of the past 200 years through a rush into isolation and self-regulation!

This unprecedented total mobilization to slow down the pandemic is emblematic of times of biological warfare and totalitarian regimes, now reinforced by social media and by hundreds of people who systematically use their windows and balconies to show solidarity to those actively fighting the pandemic. But this solidarity is haunted by the certainty that ontological intimacy is inevitably undermined, that biological and meaningful contact and interaction between humans is going to be worsen by COVID-19. This official state of permanent war disrupts already fragile intimate, inter-species and intersectional solidarities, giving us more reasons to fear others, the unknown, the person in front of us – anyone BUT the system that created it. Social media blows up in trivial racial jokes or even hate instigations. There are many calls for renewed forms of solidarities and intimacy. Climate change has long been a call for multiplying care towards greater forms of justice, socio-environmental, climate, or intergenerational. More than ever, we must return to local communities and to our networks of affective support.

One of the main struggles we should be engaging with is the struggle for our memories, to remember our collective traumas. Resisting the normalization of suffering and fear could also be a means to understand and handle collective traumas. For one of the paradoxes of such experiences is that they can intrude our memories even when we try hard to forget them.

The pandemic could make us embrace vulnerability NOT as a pathology that cannot possibly stand the inevitable exposures we have to many Others (Velicu and Garcia-Lopez 2018). Isolation and security could also be a mode of collective reflection on our common and different vulnerabilities and mutual boundedness. Unchosen proximity to scary ‘others’ is part of the human condition that we cannot deny without crucial losses. Whatever may seem like risk, it must be taken because no enclosure is ever complete. Processing the trauma of isolation and disconnection should be less of a private online business and more of a call for new intimacies and communities of care.

António Carvalho currently works as a research fellow at the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra. He holds a PhD in Sociology. His research interests include the Anthropocene, ontology, affect and post-humanist theory.

Irina Velicu is a political scientist working on socio-environmental conflicts in post-communist countries at the Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Portugal. She is currently the Principle Investigator of the project JustFood: From Alternative Food Networks to Environmental Justice, which expands her work by looking at food justice in Europe.

References

Agamben, G, (2020). The state of exception provoked by an unmotivated emergency.

Benvenuto, S. (2020). Welcome to Seclusion.

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York: Random House.

Sloterdijk, P. (2013). You must change your life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Swyngedouw, E. (2010). Apocalypse forever? Theory, culture & society, 27(2-3), 213-232.

Swyngedouw, E., & Ernstson, H. (2018). Interrupting the anthropo-obScene: Immuno-biopolitics and depoliticizing ontologies in the anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society, 35(6), 3-30.

Velicu, I., & García-López, G. (2018). Thinking the commons through Ostrom and Butler: Boundedness and vulnerability. Theory, Culture & Society, 35(6), 55-73.