By Roberta Biasillo

What happens when our behaviours do not match the expectations of the individualistic neoliberal academia?

This blog takes off from the closing question that Marco Armiero, Stefania Barca and Irina Velicu left open in their “Minifesto” for Undisciplining Academia: How could different praxes come together as part of a wider Undisciplined Zone of Academia? I will explore what happens when our behaviours do not match the expectations of the individualistic neoliberal academia. The fact that we feel, and we actually are, trapped in such a system does not mean that we are not aware of it and we are not fighting back. We are indeed claiming a different academia, we are practicing and theorising it.

The book Block, Source: The Telegraph.

What makes academia different from a multinational company nowadays? We, as scholars, really need to reflect more on this question before anything else if we believe that knowledge represents a public service and a non-negotiable component of human dignity. In our neoliberal higher education, institutional rules became empty shells and legal proceedings proved themselves to be protecting existing systems. Neoliberal academia is indeed an oxymoron: neoliberalism is erasing the specificity of academia in relation to other working environments.

To highlight the failure of the neoliberal educational agenda, we have to show that an alternative model is not only able to produce better research outputs, but is also able to build intellectual communities and societal engagement both inside and outside of university departments. As Laura Pulido argued in her open letter to all the potential scholar activists, we are requested to keep “high standard of both scholarship and social commitment, showing that the two are not mutually exclusive.”

Recent reforms pursued the marketization of teaching and researching services, extremely flexible, short-term and multitasking working conditions, the commodification of education, continuous and managerialist practices of assessment. The neoliberal agenda axed part of our asset as individual beings and research collectives, transforming our capabilities into segments of a rationalising and productivist programme. Research conditions and recruitment assessment tools forced us to label collegiality, equality and diversity as neglected and unavoidable shares of value; as “surplus”, “plus-value”, or “added value”. Our humanity, which is the ability to express ourselves and to create social infrastructures, is not formally measurable and does not have a line in our curricula and, most relevantly, is not even informally considered in the institutions where we work when it comes to assign scientific and research roles.

To my experience, the inability to acknowledge humanity – in more neoliberal terms, team-building skills – is exactly what generates mental health problems, disaffection, feelings of loneliness and overexploitation.

Photo by Quinten de Graaf. Source: Unsplash.

There is more. Such a quantitative scheme in fact did not turn successful, did not turn rational, and did not turn productive, at all. Quite the opposite, it has increased the costs for universities and national health care systems; insecure employment is leading to bad research output and is limiting the scope and depth of our projects. Current assessment processes externalise the very essence of academia and transform it into hidden costs. Neoliberalism builds on the myths of rationality and productivity and we, as researchers, are called to unveil its fake assumptions and promises.

Let´s consider for a minute the calls we have read and the positions we have applied for. They all appear inconsistent for at least three reasons. They all place great emphasis on the exchange of ideas among fellows and the spirit of community within the larger institution but moments of collegiality I have encountered were generally due to individuals´ personal, non-enumerated and mostly unpaid efforts. They all search for gender balance, but without a feminist approach and feminist practices, formal equality remains on paper. They all call for diversity, but papers published in any language but English value more or less zero in the academic international market and universities still are monolithically white places that haven’t looked at their curricula. These discrepancies between what is required and what is valued causes psychological distress in scholars, and especially (but not exclusively) in early career scholars.

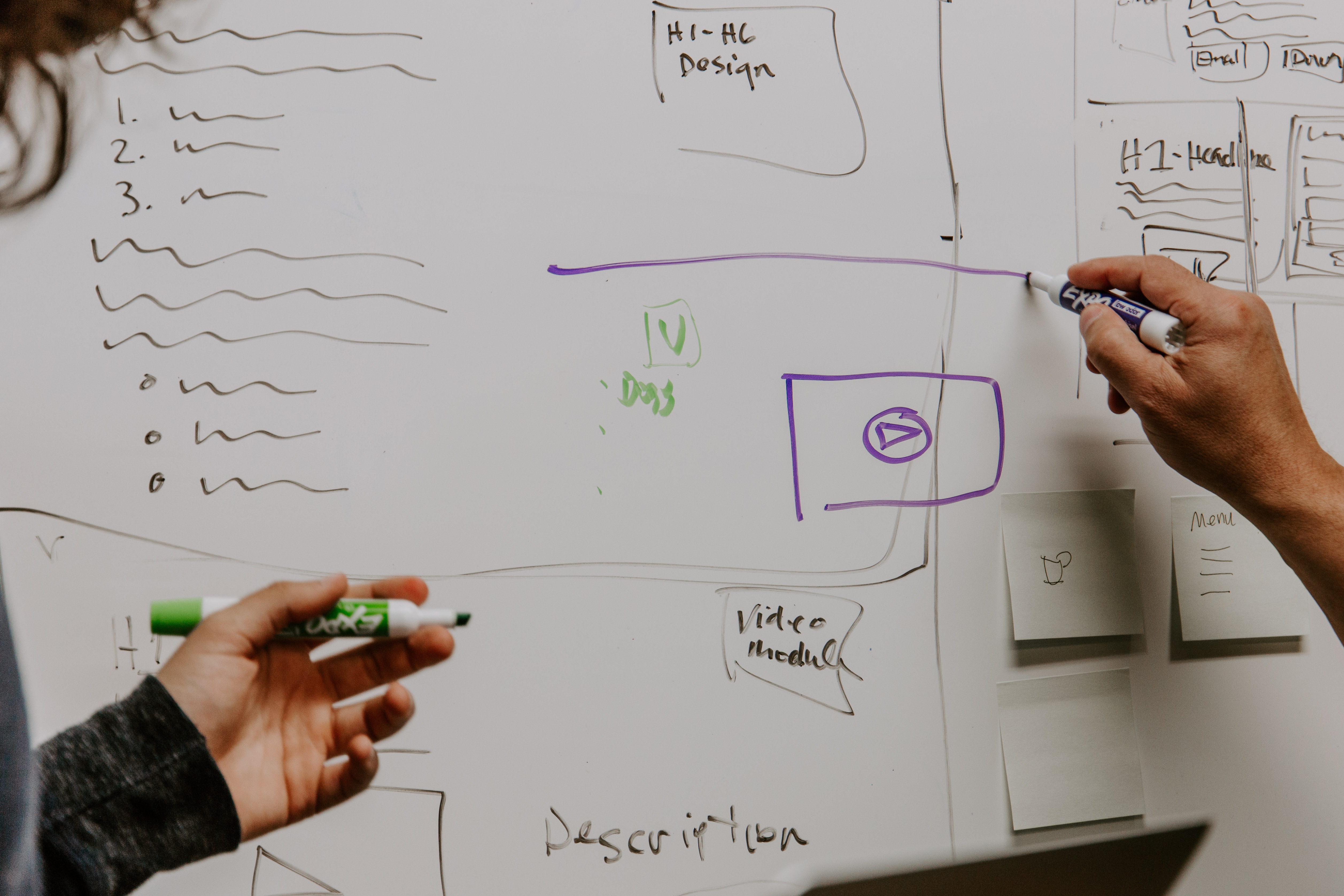

Photo by Kaleidico. Source: Unsplash

Contradictory universities mirror distressed academics. We need to agree on this if we want to underscore the connections between personal experience and larger social, economic and political structures. The slogan the personal is political is still valid, and should allow us to see present and future alliances and get organised. Collegiality, equality and diversity cannot be considered as plus-value, cannot be extra costs weighing most vulnerable researchers down, and those goals cannot be achieved via institutionalization. The personal is political has thus also other meanings, namely being solidly aware of what we would like academia and academic relationships to be and walking our talk responsibly.

The Bologna process has been quite willing to mess around with essential features of European higher education with the clear political aim of undermining the specificity of academia and transforming our departments into containers and dispensers of projects. The downsides of such enterprise are not accidents; they demonstrate that high quality researches must rely on social infrastructures; they urge us to elaborate different academic models.

Why do we need an alternative? Because many of us are facing severe consequences, although we are acting responsibly and feel entitled to speak up. When our working time and energies do not feed our curricula with peer-reviewed papers and monographs, we get frustrated and burned out but we know that we are pursuing our own vision of academia.

How to build an alternative? Whenever we devote our own time to foster collaborations, if our idea of cooperation with colleagues means care and mutual empowerment, and if we feel transparent and underestimated in doing and thinking so, we should forget about those feelings. Let´s tell ourselves every day that we are relevant and entitled to be as we are. Let´s remember every single day that we have the power of not having power, which means being free, even if at our own risk. If we have a colleague who creates collegiality, we should give that person scientific relevance not only administrative tasks; when we write working contracts, let´s be sure that we are providing everyone the same dignity, which translated in bureaucratic terms should sound something like “distributing tasks fairly”.

Roberta Biasillo is an environmental historian currently employed at the Environmental Humanities Laboratory, Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm (Sweden). She is part of the FORMAS-funded project Occupy Climate Change! She is carrying out a research on fascist colonial ecologies, particularly in North Africa. In 2017-2018 she has been a fellow at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich (Germany).

Just to focus on one area, we need to resist the neoliberalisation of academic publishing, and fight off so-called requirements to publish in certain commercial journals. ‘Other outputs matter’, as we try to demonstrate in the [trilingual] Journal of Political Ecology. I actually think it is a bit hypocritical to expound a strong critical or left or feminist argument that is against capitalist exploitation, and then publish it in a journal that makes thousands of dollars from it for one of the big five commercial publishers, by charging our libraries for a subscription to that journal or charging the author $3,000+ to retain copyright and publish OA.