by Roberta Biasillo and Marco Armiero

What if we let Italy talk through its forests? What if we unfold Italian history through its forests? Today’s blog discusses Italian forest narratives and how they may be read.

This article was originally published on whitehorsepress and is inspired by an article published in Environment and History.

“That Italy’s embodied narratives begin or coincide with the natural-cultural features of its territory is obvious. This happens here just like in any other part of the world. Maybe more than other countries, however, Italy is almost inevitably synonymous with its landscape … Italy talks through its territories and ecologies.”

(Serenella Iovino, Ecocriticism and Italy. Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation, 2016)

Echoing Italian geographer Eugenio Turri, forests are ‘palimpsests’ storing pasts (Eugenio Turri, Semiologia del paesaggio italiano, 2014. First ed. 1979), always reused and always altered but still bearing traces of their earlier forms. Italian forest landscapes are sites of stories, memories and histories.

What if we let Italy talk through its forests? What if we unfold Italian history through its forests? In some cases (hi)stories are still hearable in people’s memories and seeable in present-day environments whilst in other cases collective memories and landscapes have flattened out, current pictures fire our imagination and the past becomes again the realm of historians.

All Italian forests root into their own past and are, among other things, their past. National discourses and practices pop up every now and then. In certain conditions the past does not simply re-emerge, and indeed it flourishes. A few examples.

Since 2002 in Piedmont, northwest Italy, the forests of the alpine Susa Valley have started to be seriously threatened by the project of a high speed railway line considered by the state to be of ‘strategic interest’. The creation of this infrastructure between Turin (Italy) and Lyon (France) triggered the insurgence of the NO TAV (No to the High Speed Train) movement along with the militarisation of the area and the brutal repression of any form of grass-roots protests by the state.

Stop the militarisation of the Val Susa Valley and the TAV! Source: Italy Calling. Italian Tales of Oppression & Resistance.

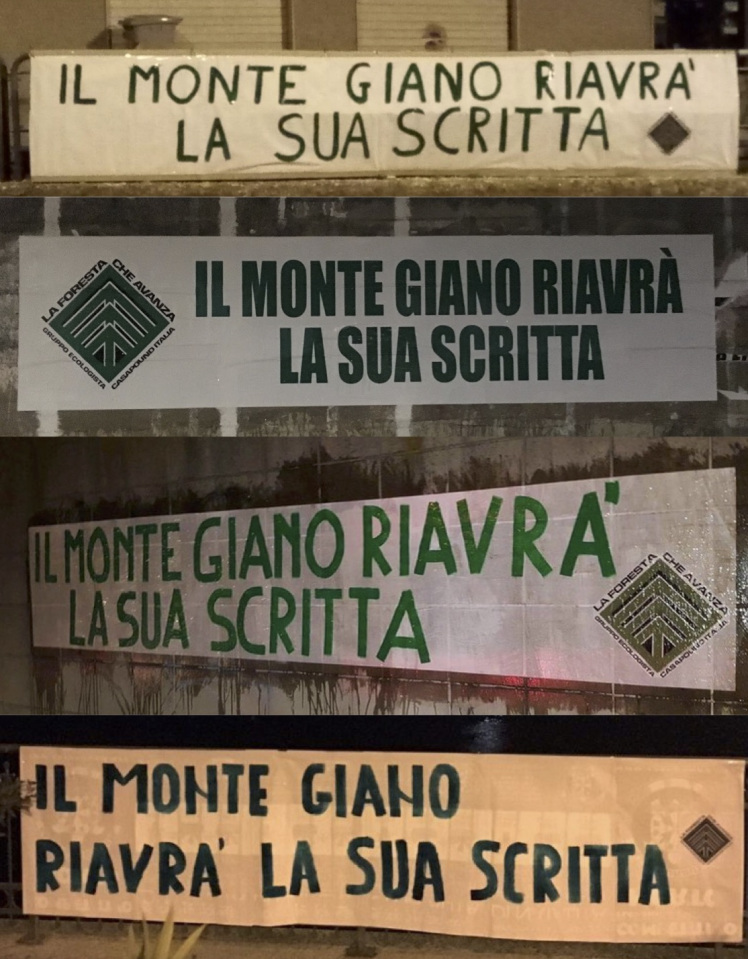

A second interesting occurrence happened in central Italy in the aftermath of a fire in August 2017. The burning of 20,000 pines on a landslide-prone slope hit the headlines because of its controversial legacy, rather than for its ecological – stricto sensu – damage and ensuing hydrogeological hazards. The forest close to the city of Rieti, northern Rome, was planted in 1938–1939 and intended to be a homage to Mussolini. As a matter of fact, the pines occupied a well-defined space so that from afar everyone could distinguish the letters DVX forming the fascist leader’s title in latin. Neo-fascist groups proposed, after the fire, to re-plant the monument as a form of historical preservation.

In a recent blog post, historians Wilko Graf von Hardenberg and Marco Armiero discussed the case and argued that recreating this past national(istic) emblem is not just a matter a conservation – either historical or natural – but ‘rather an action with much symbolic and political value’. In democratic times, could it make any sense to remake a ‘fascist forest’ on purpose and still pay homage to a dictator?

‘Mount Giano will be planted again’. Source: whitehorsepress.blog.

Nevertheless, most Italian forests seem scarcely readable and in our essay we selected three of them: the Fontana Forest near Mantua (northern Italy), the Follonica Forest in Tuscany, and the Monticchio Forest in Basilicata region (southern Italy). Instead of being three long-standing forests, they are generally considered natural landmarks and protected areas. An undisputed present layer resting on nature conservation and leisure narratives superimposes itself on a multifaceted past.

Interestingly enough, recently these areas have acquired and are acquiring new forms of signification: the Fontana Forest symbolises the quintessential urban forest and the city of Mantua will host the 2018 World Forum on Urban Forest; the Magma Museum in Follonica is contributing to the rediscovery of the industrial past of its wooded surroundings; only in 2017 the Basilicata Region secured the Monticchio Forest establishing a park strongly connected to the memory of the 1860s peasant insurgency.

So far, the legal status of protected area represents generally the last, in chronological order, strategy of nationalisation, the last frontier of modernisation. We have tried to go beyond the notion of park and to search for other national trajectories into forests, or forest trajectories into the nation.

Map of Italian Protected Areas. Source: parks.it.

Historical accounts have showed how forest spaces have encompassed various uses, meanings and purposes, thus representing contested sites. Because of that, top-down understandings and state projects aimed – and still aim – to include wooded regions into the vast array of national constructions, strategies, and transformations (Marco Armiero, A Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy, 2011).

Assuming all this, we have analysed the connection between such a peripheral landscape and Italian nation-building and modernisation processes in the nineteenth century. Specifically, we have addressed these three last and least readable spots searching for hints and clues and mainly using the tools that we, as historians, are supposed to have – archival files.

Forests are not just made of trees and if you are willing to see the nation for the trees, you may be interested in reading our essay in Environment and History.

Roberta Biasillo is a research fellow at the Rachel Carson Center, Munich and is affiliated with University of Roma 3, Italy. Marco Armiero is the Director of the Environmental Humanities Laboratory at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.![]()

Reblogged this on Political Ecology Network.