ENTITLE Blog presents two reflections on the dystopian world of the Handmaid’s tale. In the second contribution, Joël Foramitti comments on the different ways that gender, exploitation and nature play out in the politics of the Handmaid’s tale. Here the first contribution by Júlia Hosta Cuy.

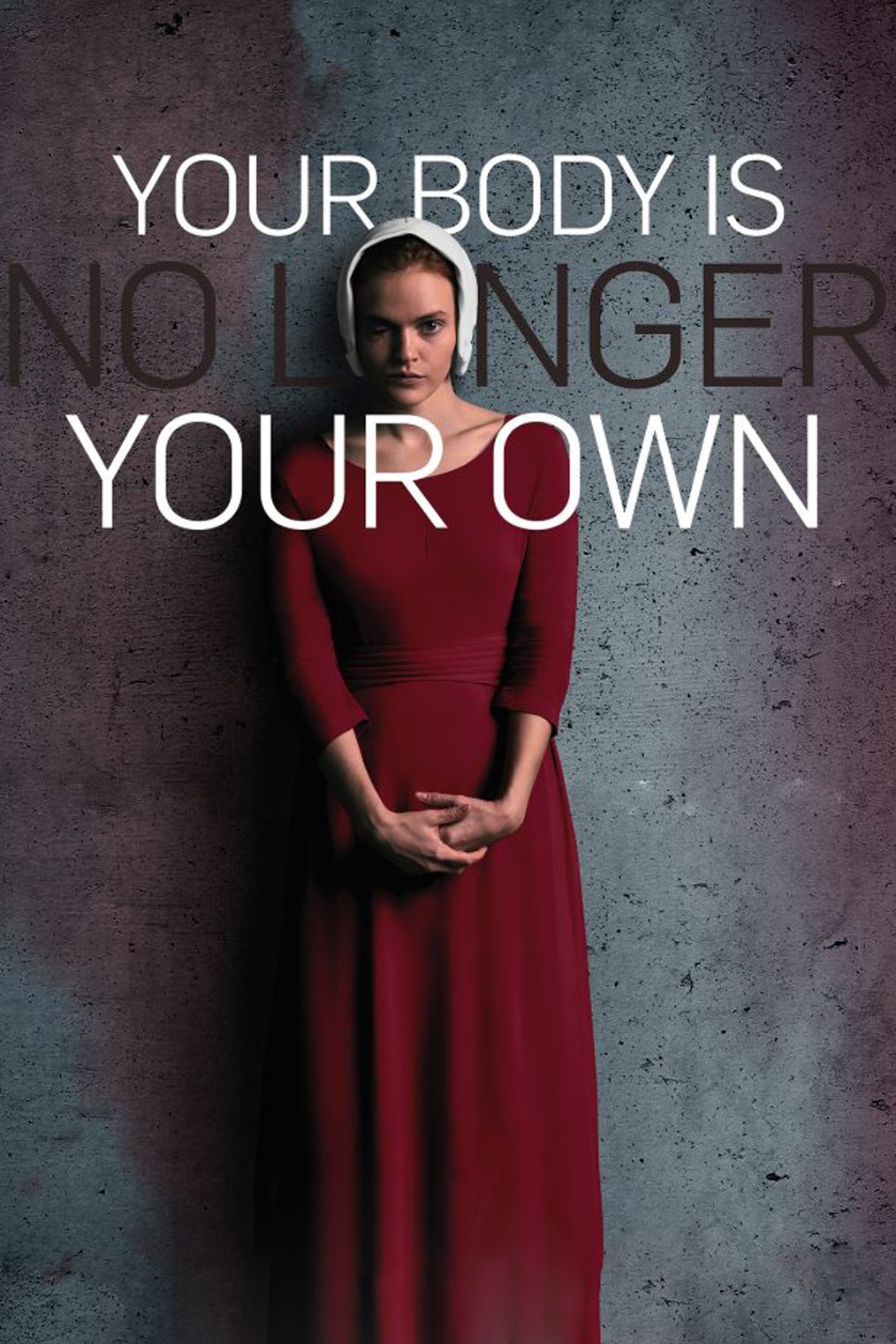

The huge success of Hulu’s 2017 web television series, the ‘Handmaid’s tale’ (receiving widespread critical acclaim and eight Primetime Emmy Awards including Outstanding Drama Series) brought back to attention Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel of the same name. The book and the series are situated in a not so far future, where the theocracy of Gilead has established itself in parts of Eastern USA after a Second American Civil War. A group of fertile women in Gilead, called “Handmaids”, is forced into sexual and childbearing servitude. The chilling parallels with USA in the Trump era did not escape viewers or critics, pronounced in the TV series with a visual aesthetic that made the dystopia eerily contemporary.

Scarcity and the control of bodies in Gilead

by Joël Foramitti

Atwood probably did not write “The Handmaid’s Tale” by chance in 1984. A modern dystopian classic, it is a tale about power and desire in a society where women have been enslaved for their “biological destinies” (this and following quotations are from the 1986 edition of the book).

As Margaret Atwood claims, science fiction is really about now. Just last year, a widely reported study claimed that the most effective way to fight climate change is to have less children. Debates about overpopulation go back to Malthus’s infamous 1798 “essay” or Jonathan Swift’s 1729 satirical “modest proposal” to sell the overabundant children as a delicacy to the rich. Atwood took such thoughts and turned them upside down. In her tale, instead of population growth putting strain on limited resources, human impact on the environment has made children themselves a scarce resource. Only a tiny share of women has remained fertile in Gilead – too few in fact to justify their freedom. But just like with the supposedly limited resources of our time, one should raise the central question of political ecology: too few for what? And for whom?

As Marshal Sahlins argued scarcity is always a relation between means and ends. After the severe environmental crisis insinuated in the story, a shrinking population could be just fine if the survival of humankind were to be the goal. The drop of fertility itself is not really the source of conflict in the story. To get as many children as possible was never the aim of Gilead’s commanders. It was only their justification to control women and reproduce their class and power.

Their main ambition was to seize the power over reproduction that had suddenly become so significant. Anarcho-feminists like Emma Goldman have since long pointed out that conscious procreation – the decision of women to limit their reproduction – can be a political act, an act of intentionally refusing the exploitation of their bodies and refuse to produce labor for factories or armies. Read from this perspective, the handmaid’s tale is a story of how this apparently fundamentally female political power was taken away from women and obtained by the commanders in their effort to consolidate power.

How could something like this happen? Atwood gives us cues. A Christian cult took over the government using alleged terrorism, the confusion in the midst of an environmental disaster and the sudden drop in fertility.

“It was after the catastrophe, when they shot the president and machine-gunned the Congress and the army declared a state of emergency. They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics, at the time.” (Offred, Chapter 28)

After that, they maintained the face of a stable government, running just as before, and went on to dispossess women step by step of their rights. It wasn’t difficult to execute their plans. There was already an existing patriarchal culture, a gender-separated and technology-based institutional system.

“If there had still been portable money, it would have been more difficult. […] They’ve frozen them, she said. Mine too. The collective’s too. Any account with an F on it instead of an M. All they needed to do is push a few buttons. We’re cut off.” (ibid., Chapter 28)

To control reproduction, they had to go further. To institutionalize a right to rape for the ruling class, they had to establish consent of the population. Utilizing quotes from the bible, the regime indoctrinated the fertile women in re-education centers where in Gramscian fashion they selectively mobilized some [already existing] common senses, while leaving out and erasing others. The laws of Gilead were framed as something natural and divine, and the members of upper class households got to reproduce them and embody them in the monthly ritual, or more appropriately rape, ceremony.

“It’s the usual story, the usual stories. God to Adam, God to Noah. ‘Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.’ Then comes the moldy old Rachel and Leah stuff we had drummed into us at the Center. ‘Give me children, or else I die. Am I in God’s stead, who hath withheld from thee the fruit of the womb? Behold my maid Bilhah. She shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her.’” (ibid., Chapter 15)

And thus, the handmaids came to be: a new class with the sole destiny of lending their wombs to the commanders and their wives.

But the story leaves an opening of hope. As the story of June moves on, it becomes clear that the regime has not established a cultural hegemony. It still depends on violence to coerce. The bodies of hanged rebels all around the streets, remind us that all is not well and set in Gilead.

In the epilogue, and in a beautiful twist, the novel reveals itself to be a collection of records discovered – and interestingly, arranged by male researchers – in a future society that has survived the horrors of Gilead. Just like in George Orwell’s “1984”, Atwood has given her tale a careful note of hope.

“Sanity is a valuable possession; I hoard it the way people once hoarded money. I save it, so I will have enough, when the time comes.” (ibid., Chapter 19)

For many, Atwood’s story feels appallingly real, given the recent developments of our times. That might be because, in contrast to proper science fiction, Atwood aimed to write speculative fiction that does not include any fictional technology, beings or phenomena, but in her own words, “employs the means already more or less at hand”. With few more years of political alienation and environmental destruction, we might be exactly at the starting point of her story.

Joël Foramitti is a Master’s student of Ecological Economics at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Reblogged this on Political Ecology Network.