By Jonathan Coward*

Warnings over climate change are often dressed in the language of apocalypse, but is well-intentioned alarmism having the required effect?

“Suddenly there is an earthquake. Suddenly the sea floods the city, pouring down through the mouths into the corridors of council and institute and short-circuiting everything… How’s that for an ending?”

“These banal world destructions prove nothing but the impoverished minds of those who can think of nothing better.”Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in Four Books, p.497

The above dialogue is taken from the Scottish epic, Lanark: A Life in Four Books, by Alasdair Gray. The protagonist, Lanark, meets his ‘creator’, the thinly veiled Gray, penned into his own story as the omniscient, god-like author. A curious Lanark asks of his own future, and the future of his home, only to receive a hopeless, fatalistic response. Later, as the book draws to a close, Lanark can only watch from a hilltop as the catastrophe he anticipated advances on the city. He becomes a spectator of decline, accepting prophecy as fate rather than acting to divert ‘the inevitable’.

Gray’s dystopian-realist novel was published in 1981, at a juncture for the planet: It was the tail end of the tense Cold War and within the decade climate change would be catapulted onto the global agenda at the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere in Toronto.

Some environmental commentators, seeking to end the ongoing global complacency over the issue, have picked up on the apocalyptic imagination to urge people and governments into action. But we are bombarded with multiple warnings of catastrophe so often that I wonder whether this really helps the wider environmental cause.

Can catastrophic discourse encourage activism, or could it instead create a something wholly counterproductive?

Apocalypse (Then and) Now

Apocalypse is a recurrent theme in environmental and climate change literature but the most pervasive apocalyptic ideas are found today in works of popular fiction. This ‘mass-culture’ – to borrow from early 20th Century cultural theorists Adorno and Horkheimer[i] – of Armageddon takes the form of film, music, literature and other consumables that feed into the popular psyche.

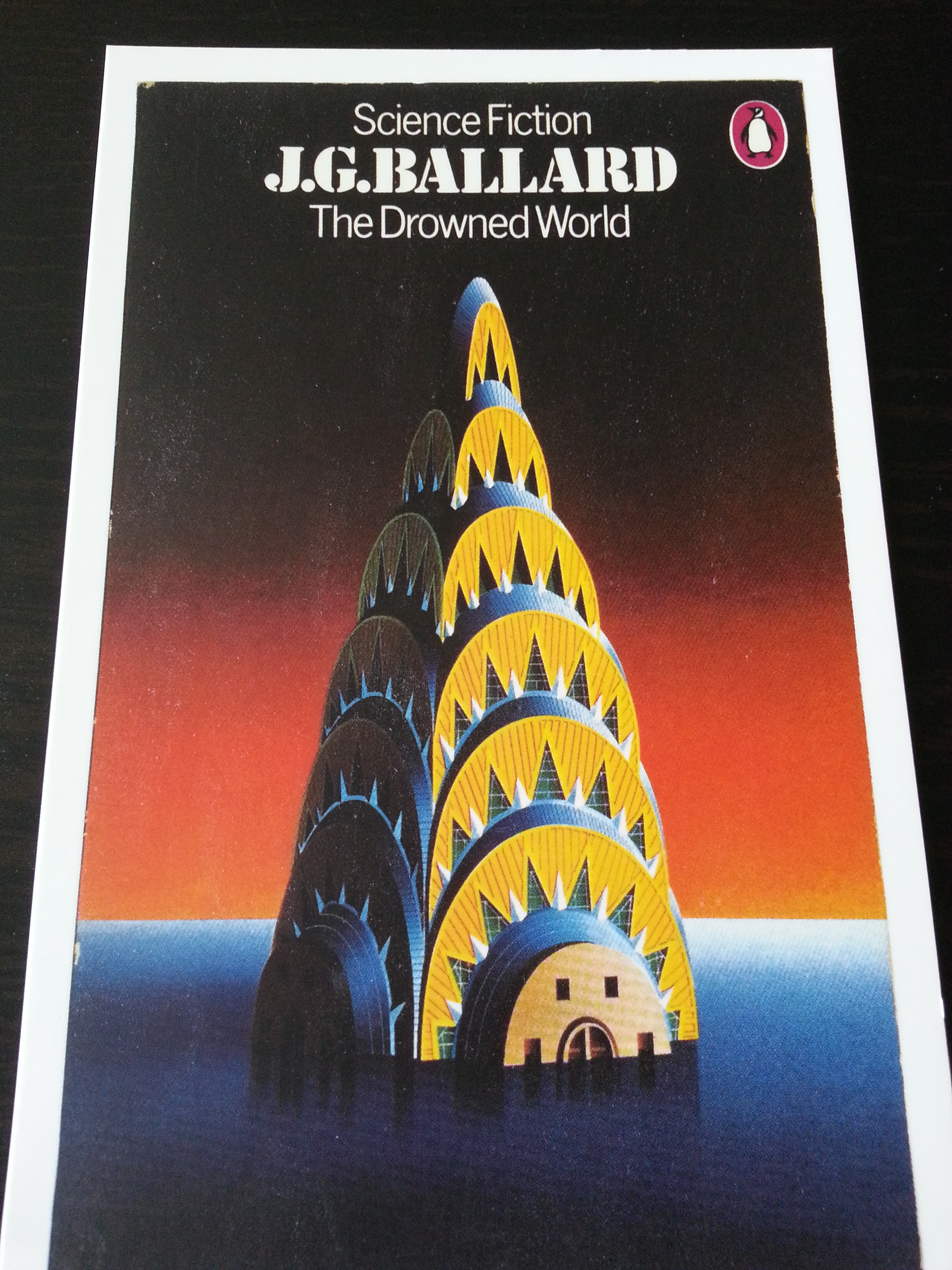

The genre encompasses sprawling themes such as manmade nuclear obliteration (Bob Dylan’s 1963 song, Talking World War III Blues), resource scarcity (the Mad Max franchise), cosmic events (the 1998 blockbuster, Deep Impact), major pandemic (contemporary comic and TV series, The Walking Dead), and, of course, environmental triggers (J.G. Ballard’s 1962 novel, The Drowned World).

With the prominence of climate change and environmental degradation in recent years, apocalyptic messages are now omnipresent in contemporary environmental literature. In classics such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, James Lovelock’s The Revenge of Gaia, or political polemics like Joel Kovel’s The Enemy of Nature, the precise cause of environmental damage differs, but the catastrophic prism through which the authors’ messages are communicated is strikingly similar. But what, exactly, does this discourse of disaster seek to achieve?

First, environmental literatures have traditionally served as a type of critical theory by being both diagnostic and remedial. Their overarching apocalyptic tone orients the commentary towards midnight on the doomsday clock by inferring that the current trajectory of society must change, or the environment and humankind will perish.

Secondly, the inclusion of the apocalyptic narrative in environmental literature is also inherently political. It is employed to increase the salience of environmental issues in the minds of the general public and to encourage change on an individual, collective and institutional level. This is a technique, which recognizes that although general awareness of environmental issues is now very high, they continue to be of low priority for most people. For political change to actually occur, inert awareness must be translated into concrete action and a transformation in consciousness is a precondition for that.

Cover of Ballard’s book The Drowned World. Source: Deco Domino.

From theory to reality: Criticisms and cooption

The popular deployment of apocalyptic discourse follows the view that if the predicted devastation is extreme, then the change in consciousness or political agenda is likely to be correspondingly radical[ii].

However, recent academic research has shown that exaggeration runs the risk of disengaging individuals from environmentally-conscious activity. In one study, participants with a ‘just’ worldview (that the world is generally orderly and stable) were exposed to information about the catastrophic consequences of global warming. The resulting trend was a denial of the climate change threat which stopped participants from adopting more environmentally friendly behaviours.

At an institutional level, the repeated failure of governments and industry to act adequately on catastrophic warnings highlights a similarly apathetic trend, as well as an attachment to a worldview that can stifle the presumed effectiveness of catastrophic discourse.

To understand this impotence, I have delved into the Cultural Studies toolkit, taking my initial cue from a passage by environmentalist Bill McKibben in his widely acclaimed book, The End of Nature[iii]:

“[In] some sense, the physical world is no longer as real to us as the economic world – we cosset and succour to the economy; our politicians gear every decision to speeding further its growth.”

This view echoes the broader phenomenon of ‘capitalist realism’, recently identified by cultural theorist Mark Fisher. Within capitalist realism (a bulked-up Marxist theory of reification) the economy assumes the role of a totalising objective reality. Everything is organised in accordance with the current neoliberal order and beyond any reasonable dispute. Applying this to environmentalism, it becomes clear that the radical intention of catastrophic discourse – to drastically alter or replace the status quo to protect the environment – can therefore be denied. It is, after all, impossible to cancel ‘reality’.

The geographer Erik Swyngedouw puts forward a persuasive case for how this is achieved in his article Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures[iv]. Environmental problems are presented as universally threatening to the survival of humankind, but the apocalyptic narratives that stem from this are so seductively populist that they resist proper political framing in the traditional left-right sense. The quasi-neutral framing of these issues suggests that the terrifying threat is an objective and technical crisis.

This, Swyngedouw goes on, intends the oversight of a managerial class of technocrats to fix the problem within the horizons of the status quo. Of course, technocracy in capitalism is never politically neutral, as shown in Greece and elsewhere. Crisis, environmental or otherwise, is therefore addressed only in shallow, economic terms, such that it ultimately serves the narrow interests of capital.

Author and environmental activist, Naomi Klein, describes numerous examples of this tendency in her popular book The Shock Doctrine, where catastrophic crises repeatedly serve as a backdrop to the alignment of state and corporate interests. For instance, following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, state schools in New Orleans were opportunistically privatised, creating an educational marketplace run by businesses.

Rooftop graffiti following Hurricane Katrina. Source: katrina.weather.com.

Like Swngedouw, Klein understands crisis as a “conjunctural condition that requires particular techno-managerial attention”[v], employed purposefully to avoid taking more drastic action. This has been especially evident in attempts to manage parts of the environment that are subject to – or subject of – the destructive tendencies of industry. Ecosystems have been valorised for the purposes of conservation (see for example the UK National Ecosystems Assessment), while carbon has been cynically commodified into credits to be freely traded within a carbon emissions trading market, thus permitting further pollution.

Using apocalyptic narratives to frame issues of environmental degradation therefore isn’t merely futile; rather the solutions it intends are regularly shut down by capitalistic institutions coopting and twisting the discourse for their own ends.

It is even possible to go further and argue that the mass-culture of armageddon mentioned earlier is complicit in capitalist realism. Take, for example, Disney Pixar’s movie Wall-E, premised on a lonely robot charged with the task of cleaning up an inhospitable litter-strewn Earth. Fisher argues:

“We’re left in no doubt that consumer capitalism and corporations… [are] responsible for this depredation… but the film performs our anti-capitalism for us, allowing us to continue to consume with impunity”.

The film also suggests that there is a placid, technological fix to the Earth’s ecological tribulations in the form of Wall-E itself. Even in post-apocalyptic dramas such as The Road or The Walking Dead motifs of capitalist ideology are present. Despite the fall of society, ideas of innate self-interested behaviour persist, in a strikingly Hobbesian ‘war of all against all’ for human flesh and scarce resources.

Wall-E. Source: The Daily Dot.

Clearly, the apocalyptic imaginary is unlikely to disappear from the popular global psyche any time soon. Despite this, we must resist catastrophic hyperbole, including the increasingly alarmist discourses adopted by climate scientists in recent years. With the shock election of serial climate change denier Donald Trump to the Oval Office, the need for an effective, cohesive environmental discourse is now more pressing than ever before.

References

[i] Adorno, T. and Horkheimer, M. (1944) The Dialectic of Enlightenment. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

[ii] Killingsworth, M. J. and Palmer, J. (1996) ‘Millennial Ecology: The Apocalyptic Narrative from Silent Spring to Global Warming’ in Herndl, C. and Brown, S. (eds.) Green Culture: Environmental Rhetoric in Contemporary America. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, pp.21-45.

[iii] McKibben, B. (1989) The End of Nature. Revised Edn. London: Bloomsbury, pp.xxiii.

[iv] Swyngedouw, E. (2013) ‘Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures’, Capitalism Nature Socialism (24)1, pp.9-18.

[v] Klein, N. (2008) ‘The Shock Doctrine’. London: Penguin Books, pp.10.

* Jonathan Coward is interested in the meeting of Political Ecology and popular culture. He studied Environment, Culture and Society (MSc) at the University of Edinburgh.

Very interesting article, thank you.

I have often heard environmental sceptics refer to how for decades environmentalists have been talking about crisis and doom and it “hasn’t happened yet” which makes them more sceptical. Of course, this is a misunderstanding of the time scales of planetary change, but it says something about environmental communication and the (over)use of “crisis messaging.”