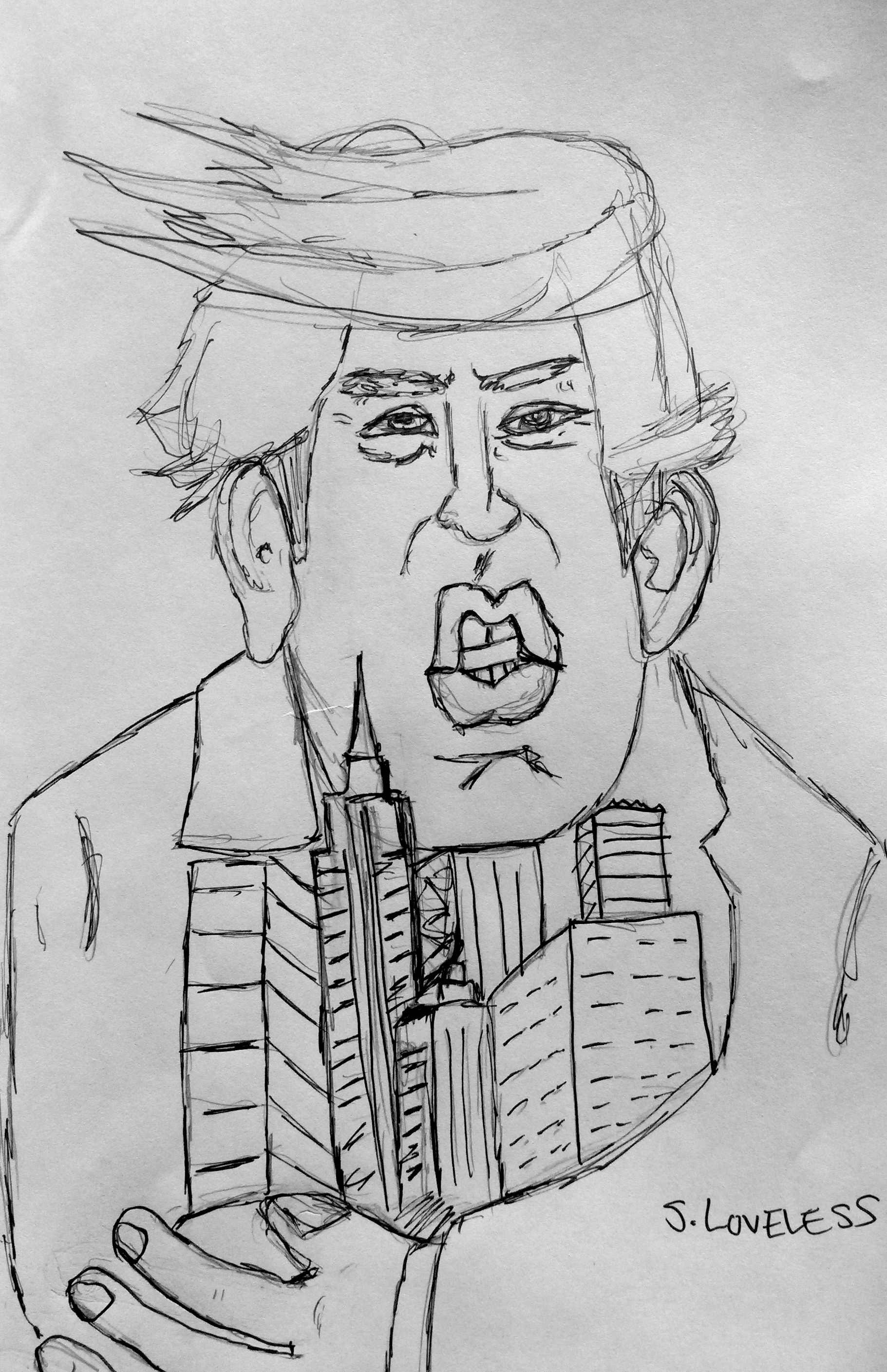

by Stephanie Loveless*

Racial issues have taken central stage during the US presidential elections. Understanding race as a fundamental dimension of any struggle for justice, it is critical to not only assess candidates’ past and present racial politics but also to consider one’s own racial positioning on the eve of the vote.

I live in Europe but as an American citizen, in the four years since I left, I have been following closely how structural racism has made its way back in US politics. Movements like Black Lives Matter, the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline and the long and drawn out election cycle, all contributed to me better understanding my own country. Leaving helped me get a better view on home. The Black Lives Matter movement has brought up issues of race, ethnicity and privilege that I haven’t really been confronted with since I was young. I sort of just floated through most of my life enjoying the privileges that came with my white skin color and a British surname, living in an almost all-white bubble called Boulder, Colorado. This bubble of white privilege isolated me further from the parallel world of Jim Crow, that black Americans continue living under until this day, despite the progress made by the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

What is ironic is that I spent much of my childhood sitting on my grandmother’s kitchen counter on the weekends watching her prepare Mexican food for the weekly gatherings that my grandparents would host. If I wasn’t watching her cook, I was trailing behind my grandfather, helping him fulfill his household duties in preparation for guests for the Domingo En La Casa meeting. Domingo En La Casa was a mentor-mentee program my grandparents organized for students of color at the University of Colorado because they recognized that there was an absence of academic support for minority students attending the university. As children of first and second generation Mexican immigrants and former activists of the Chicano Movement in the 1970s, also called El Movimiento, my grandparents had dedicated their lives to creating a support network for minorities. My grandfather, or Profe as his students called him, is still actively involved with Latino communities in Denver.

While growing up, our Mexican heritage was omnipresent through art, yearly traditions, songs, food, politics, but sadly, only occasional Spanish. Memories of that rich culture will always be part of my personal fabric, but the strange thing is that not speaking Spanish, having this strange sounding British surname, having white skin and growing up in Boulder set me apart from the other Latino kids who often had darker skin, Latino surnames, spoke Spanish and whose parents were first or second generation immigrants. Clearly, my experience was and would continue to be different from theirs, but we obviously shared some aspects of our cultural identity. Yet, I often found that I have to explain why I feel Latina, because I don’t look like Latinos are supposed to look. At the same time, I’ve most certainly experienced white privilege, if for nothing else than my skin color.

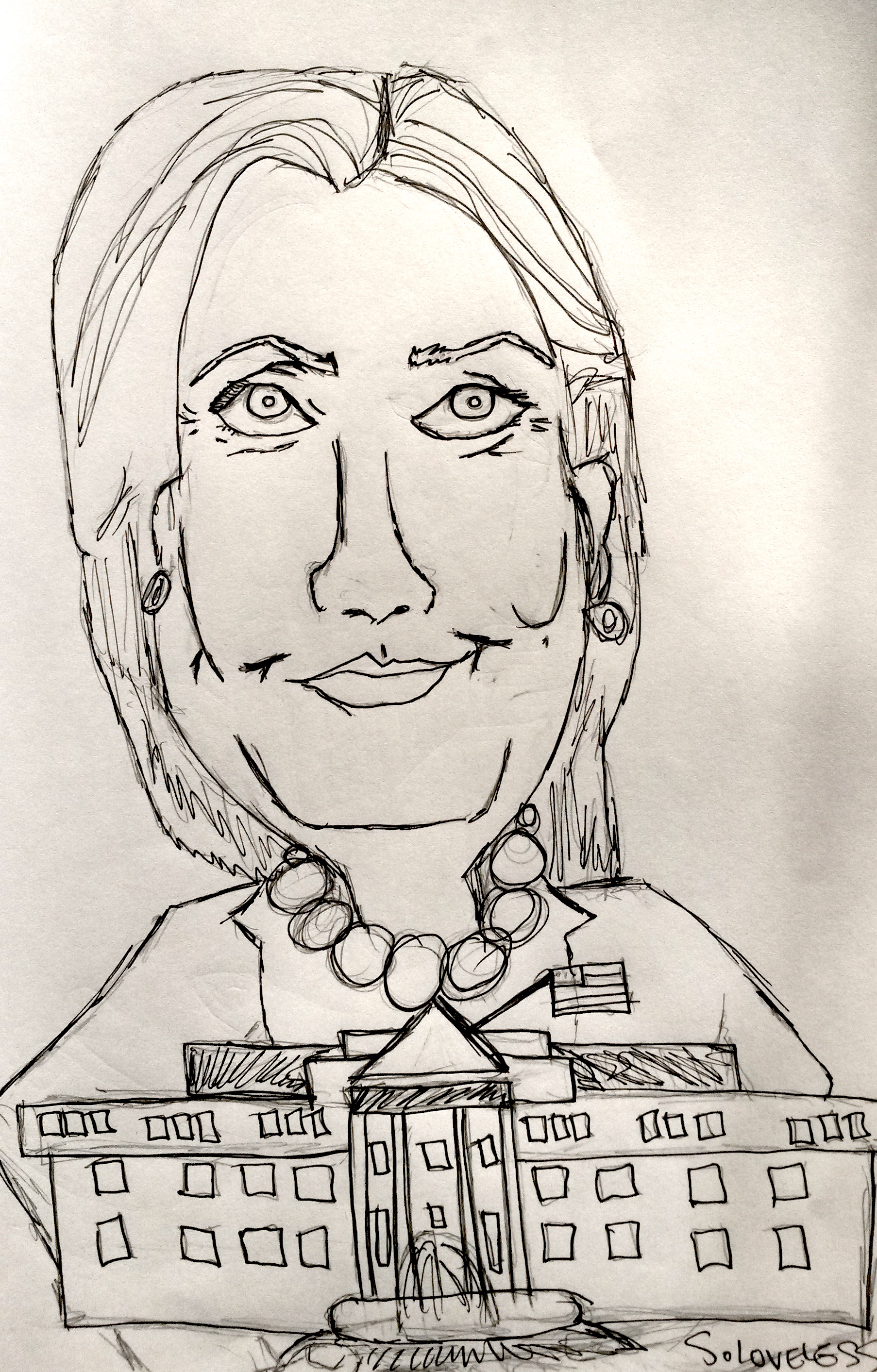

Such reflections on my identity, personal politics of race and what white privilege has meant to me have been coming up with the increasing public debates on race relations in the US, as probably has been for many Americans reexamining these issues for themselves. In fact, we are currently witnessing a turning point in race-relations in the US that can no longer be ignored. Demands are being made from both sides of the political party aisle. Trump is seemingly appealing to the white middle and working class Americans, while Clinton’s followers tend to be the educated elites, women and minorities, many of them likely in similar identity quests that I find myself in. Next to various key issues that unite and divide people in the US, the election could also be a deciding factor over how the US plans to answer these calls. The election results will also tell a tale of how Americans think about, and identify with, race in the United States, as well as an indication of whether ethnic minorities and people of color can exercise their right to vote without obstruction.

Universal suffrage?

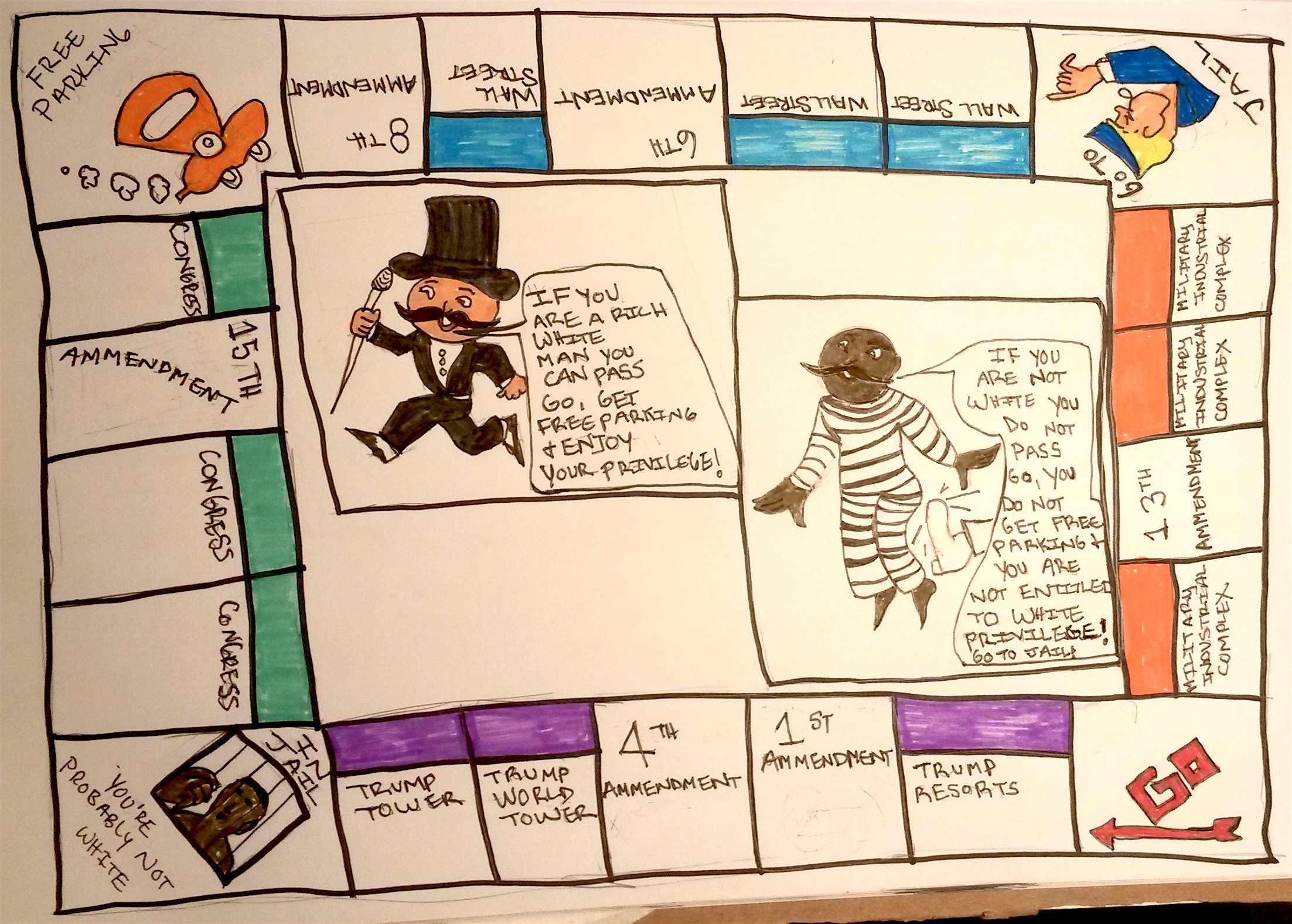

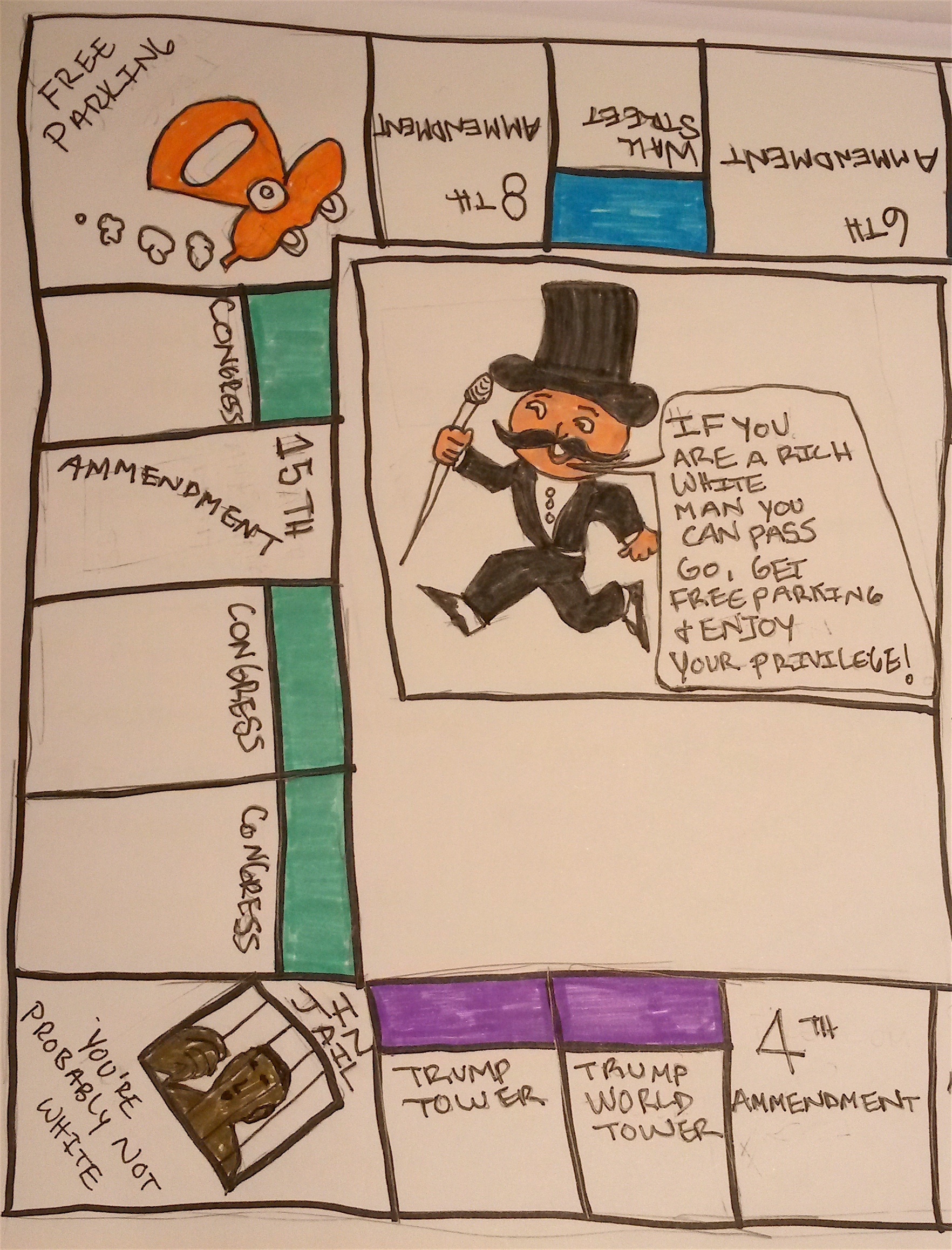

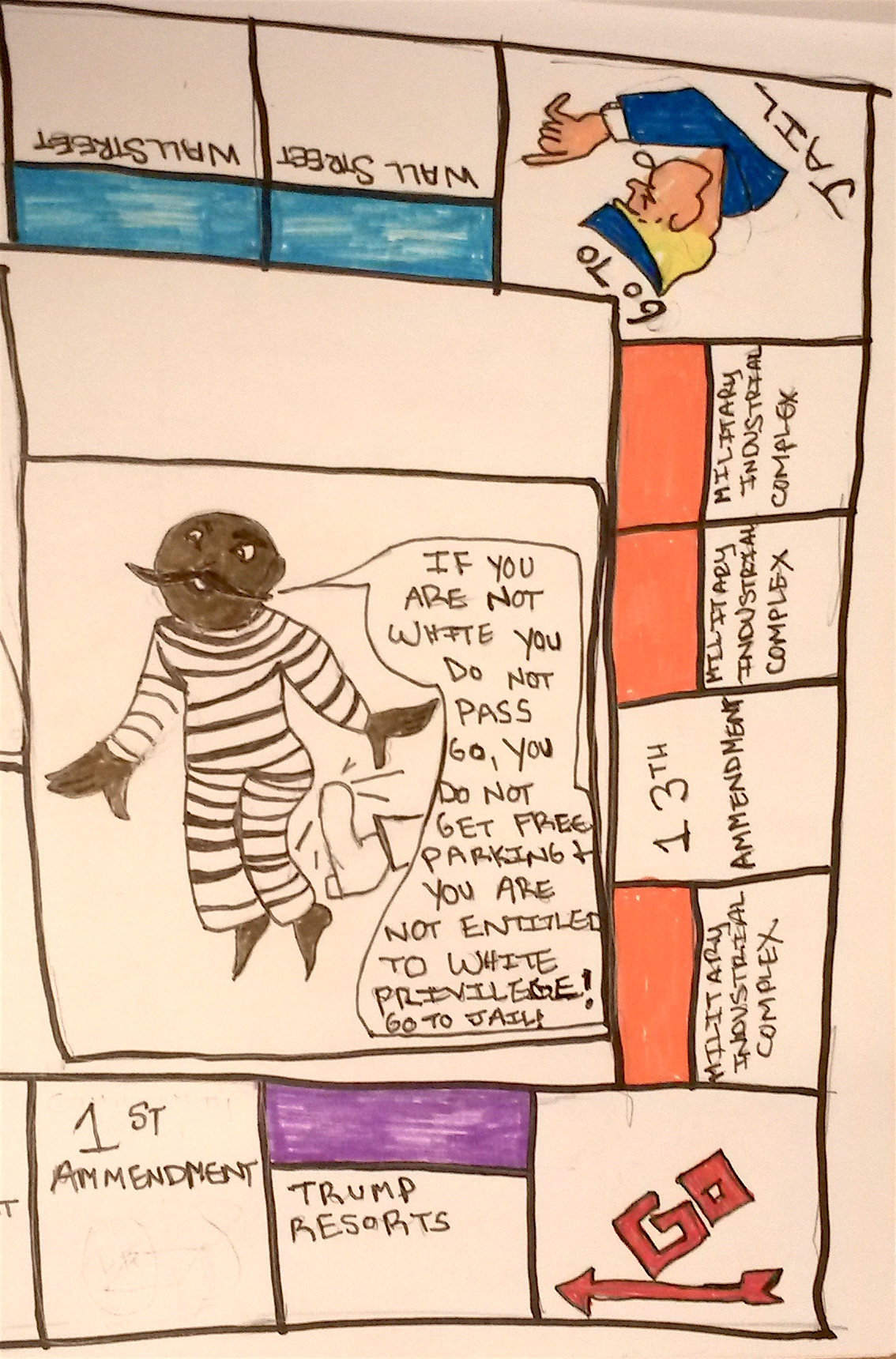

Despite living abroad, I do have the right to easily cast my vote by email. Yet for many people living in the US it is not that easy. In the 2012 election, only 53.6% of those eligible to vote did cast their ballot. Millions of Americans are not eligible to vote. Black people, Latinos and Native Americans are disproportionally affected. Of those who are not eligible, many have lost this right due to previous felony convictions, also referred to as felony disenfranchisement, and the majority of these people will never be able to vote again. This racialized voter disenfranchisement came up during the era of the so-called war on drugs that targeted black people and led to mass incarcerations until this day.

In fact, the war on drugs and crime continued from Nixon on with Ronald Regan (and all subsequent presidents of the US) who likely recognized the value of an anti-black campaign to win the vote, as shown vividly by the recent documentary 13th. Republicans above all recognized the value of suppressing the black vote, because blacks have traditionally tended to vote for Democrats. Voter suppression keeps millions of people from voting through purging of voter rolls, bureaucratic hurdles for registration, requirements for showing multiple voter IDs, etc. And for those people who do get to vote, there is always the option of racial gerrymandering to render these votes ineffective. As long as voter suppression is part and parcel of electoral politics in the US, we will continue to have deeply polarized camps of mostly white people united against all colors and ethnicities.

Another influencing factor in placing importance on the issue of race and ethnicity in this election has been a consideration of the ways in which the Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s past business and political engagements have impacted (and will likely impact) minority groups.

Siding with the Southern strategy

Hillary Clinton will probably never live down the ‘super predators’ comment but she has got the black and Latino vote anyway. Clinton’s history with racism can’t be separated from Bill’s, since she supported his strategy of the war on drugs to gain the vote, creating the 1994 Crime Bill and taking a damaging chunk of support from poor families with his Welfare Reform Bill of 1996. The Crime bill allowed Bill Clinton to toughen sentencing laws to include the famous ‘three strikes and you’re out’ policy as well as ratcheting down on crime through federal support for increased policing, and leaving office while the US experienced (and still experiences) the highest incarceration rate in the world. Much more money was spent on incarceration than on efforts to reduce crime, such as spending on education or investing more in communities’ services and urban infrastructure. Instead, measures like banning education grants for ex-offenders were put in place.

Yet, both Clintons now admit the damage the crime bill did for black communities, and Hillary seemingly wants to right some of those past wrongs. We have of course no reason to believe she will make needed reparations since as recently as 2008 she supported an initiative to dismantle the Aid to Families with Dependent Children. Given the cuts to invaluable welfare programs, I guess it is not much of a mystery now to see why the US has one of the highest children’s poverty rate in developed countries.

Redlining and dividing

Trump essentially got his start by riding the well-endowed coattails of his father Fred Trump, who as it is now widely known, gave him a small loan of at least $1 million dollars in 1978 to start building the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York. His father also subsequently gave him many other loans to continue growing his real estate empire. Trump’s father made his fortune by building housing for shipyard workers during World War II, later expanding to higher stakes properties in New York. During the ‘70s Fred Trump was incited to begin redlining practices as he was confronted with housing justice policies like the Fair Housing Act of 1968, stemming out of the civil-rights era in the US. Apparently, Fred was not ready for the change that was coming and he systematically denied rental applications of African Americans to reside in his properties.

Donald Trump extended his father’s discriminatory redlining tactics by denying blacks housing in buildings he owned or, if he did allow blacks to live in his properties, they were granted rental contracts in properties that tenants reported were not well maintained. Trump’s real estate ventures have a history that is deeply intertwined with US housing policy. Fast-forward to today and we all know the story of Trump wanting to build a wall to keep immigrants out, expressing overt Islamophobia and increasing ‘inner city policing’ which he announced in his ‘New Deal for Black America’.

What’s at stake?

Given the ways in which both candidates have supported and continue to reinforce structural racism in the United States, a vote for either candidate feels hopeless when it comes to positive steps in race-relations. In many respects the country hasn’t moved past the Jim Crow era at all. Yet, the 2016 presidential election provides us with a fascinating and terrifying view into American politics of race that is so deeply intertwined with electoral politics. The fact that political platforms are built around the question of race, forces many of us to pick the lesser of the two evils. And so here I sit far away in Europe thinking about how racism in the United States has become one of the biggest issues of our time and where I stand on it, as I wait to press send and cast my own vote by email. After all, how can we fight for social justice if we keep being divided over race in electoral politics? It is paramount to address the question of race, intertwined as it is to many other important battles for justice.

*Stephanie Loveless is a PhD fellow at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA), Autonomous University of Barcelona, working with the GREENLULUs research project. She is a native of Boulder, Colorado in the United States and holds a BA in Sociology from the University of Colorado and a double MSc in environmental science and agriculture at the University of Hohenheim and Copenhagen University with specializations in Climate Change and Environmental Management.