Europe’s last wild rivers are under threat from dam construction—yet hardly anyone is aware of it.

The Tara in Montenegro is threatened by 8 projected hydropower plants. Photo credits: RiverWatch.

Ten days ago I defied train cancellations and border restrictions in Central and South-Eastern Europe to make my way to Belgrade, Serbia, where the Balkan Rivers Days took place from 25 to 27 September. The meeting was organized by the NGOs Euronatur and RiverWatch, together with partners from various Balkan countries, as part of the ‘Save the Blue Heart of Europe’ campaign. The event was attended by 120 river conservationists from 16 European countries, Turkey and the US, who came together to network, brainstorm, exchange and strategize about possibilities to save the Balkan Rivers from an imminent dam craze, which is very much part and parcel of the current worldwide hydropower boom.

The Balkan Rivers, Blue Heart of Europe

The Balkan Rivers are among the last free-flowing rivers in Europe. Draining north into the Danube, or west into the Adriatic Sea, these largely wild and unspoilt rivers showcase some of the most unique and pristine riverine ecosystems in Europe and in the world. Turquoise crystal clear streams, extensive gravel banks, intact alluvial forests, stunningly steep gorges and waterfalls, and karstic underground streams, which only surface during extreme rainfall and snowmelt, form a landscape that hosts an amazing array of threatened and endemic species habitats. These include, most notably, the endangered Huchen, also called Danube Salmon, an indicator species of healthy riverine ecosystems; 203 threatened species of fish and molluscs, birdlife and mammals; the critically endangered Balkan lynx; and some rare vegetation communities.

That the Balkan rivers’ hydrological quality is unmatched in Europe was shown by a recent study, which assessed 35,000 river kilometres between Slovenia and Albania with regard to their hydromorphological condition (that is, the shape of the riverbed). 80% of the river stretches covered by the study proved to be a near-natural, slightly or moderately modified hydromorphological state (see map below on the left). In Germany, by comparison, 60% of the rivers are heavily engineered (see right-side map). The two maps also show why the Balkans have been named the Blue Heart of Europe.

Balkan Rivers: river courses marked in blue and green signify natural, slightly or moderately modified hydromorphological quality. Source: balkanrivers.net. |

Hydropower development in protected areas – seriously?

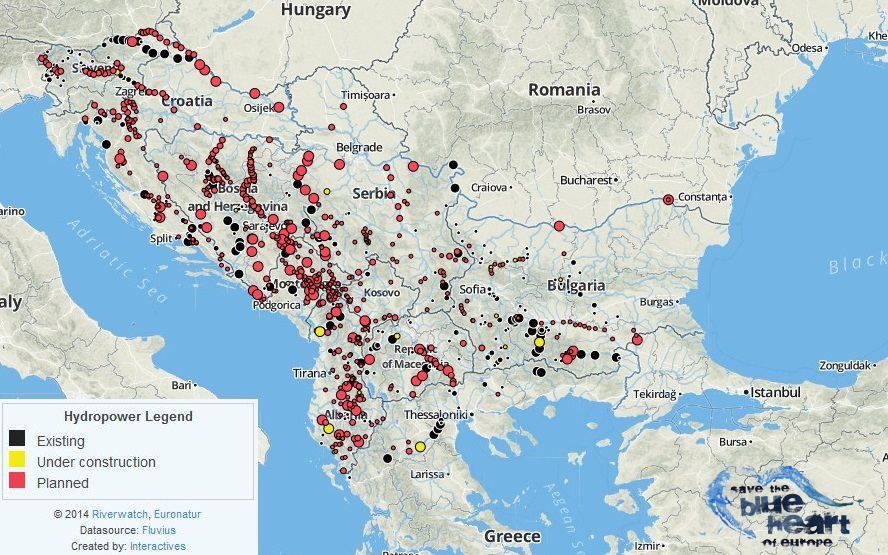

The ecological value of the Balkan Peninsula does not seem to be of particular concern to the hydropower lobby, which has clearly identified the Balkan Peninsula as a safe haven for new investments in dam construction. A recent study commissioned by Euronatur and RiverWatch has identified a total of 2,683 planned hydropower projects and 66 projects under construction (in addition to the 714 existing ones) to be developed in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, Northern Greece and the European part of Turkey. Next to medium and large-scale projects, nearly 60% of the planned dam plants are small hydro projects (less than 1 Megawatt). Yet, regardless of the projects’ size, the impending disruption of the flow and connectivity of these river basins is alarming. And so is the number of species which may be threatened of extinction.

As the opening line of a soon-to-be-released study by CEE Bankwatch on the financing of the Balkan hydro-boom aptly says, “in a region with a deadly combination of Europe’s last wild rivers, rampant corruption and inadequate nature protection, the potential for damage is immense.” For example, neither the project applicants, the financiers, nor the local authorities seem to be concerned with the fact that at least half of the planned projects are located in protected areas: national parks, Ramsar wetlands, Biosphere Reserves, World Heritage Sites, EU Natura 2000 nature protection areas, and other nature parks and reserves. As the Bankwatch researchers identified, international development banks—such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), Germany’s KfW development bank—as well as private foreign investors from Austria, Italy, Germany, Norway and Turkey are all funding projects in protected areas.

1,113 large and medium hydropower plants (>1 MW) are projected to be built across the region in the next years. See the interactive map on balkanrivers.net/en/map for a full view of all 2706 planned projects.

Sava, Vjosa, Mavrovo National Park – Natural jewels

Most Balkan countries are yet to join the European Union, and have much less stringent environmental legislation than EU member states. But EU directives seem to be systematically ignored in countries which are already part of the EU, such as Slovenia, Croatia and Bulgaria; and in prospective member states, which according to EU regulations are obliged to adhere to EU standards even during the accession process. For example, plans for the construction of about 20 hydropower projects threaten the unique ecological value of the Mavrovo National Park in Macedonia, one of Europe’s oldest national parks, up to the point where the national park status may be revoked as a result of the damage to the natural heritage. Another major river basin threatened by dam construction is the Sava (with its unique natural capacity for natural flood prevention), which flows through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia.

Likewise, plans to construct 33 hydropower plants along the Greek-Albanian Vjosa and its tributaries, one of Europe’s last pristine systems of wild and free-flowing rivers, will have impacts the extent of which we are yet to fully comprehend. A 30-minute documentary by the group Leeway Collective, shows what is to be lost: the team’s two kayaktivists take us on a breath-taking exploration of the Vjosa river, which has remained largely unexplored to date, featuring an extraordinary diversity of species and habitats (largely undocumented too).

The Leeway Collective exploring parts of the Vjosa River that can only be reached by boat. Photo by Rok Rozman.

In the Hotova National Park, the 9MW project by the Austrian corporation ENSO Hydro is under construction on the Langarica River, a tributary of the Vjosa, giving a bitter foreboding. The diversion of the river through pipes will dry up a stunning canyon, deprive an ancient Ottoman arch bridge of its purpose, and put in danger the future of the local thermal springs, which attract many tourists and represent an important source of revenue for the region. This also reminds us that well-preserved natural heritage may well have a more sustainable economic benefit for local communities, than the short-term employment gains that can be gained from hydropower development, while revenues tend to be pocketed wholly or mostly by the investors.

Dams rob the Balkan youth of their economic prospects. We should have a say in what happens to our rivers since it is our future they are planning to spoil. (K. Glojek, Geographer, Slovenia)

During a press conference at the Vjosa River local citizens and representatives of (inter)national environmental groups propose to abandon hydropower plans and to designate Europe’s last big wild river as national park. Photo by Adrian Guri (balkanrivers.net).

Collectively deciding on the environments we want

The Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign calls for immediate action. Supported by a coalition of NGOS from Austria, Germany, Albania, Macedonia, Croatia and Slovenia, and a larger network of activists from across the Balkans and Europe, the campaign advocates for the development of a master plan. The aim is to save the most valuable ecological core areas of the Balkan Rivers from the destructive impacts of dam building, while ensuring that the dilemma often mentioned in favour of hydropower (“Every country needs electricity”) is addressed.

The emphasis of the masterplan lies on a democratically derived energy concept, which determines how much energy each country actually needs and from which sources it should come; a spatial development plan that defines “no go areas” for new hydropower projects; and a legal obligation to use only state-of-the-art technology. As J. Zablocki of The Nature Conservancy aptly puts it, “the rivers of the Balkans are among the most beautiful, biodiverse and intact river systems left in the world. Whether or not they remain that way depends entirely on the decisions we make today”.

On top of that, what is needed most now is direct action. In a political context where sound arguments and legal frameworks are happily ignored, it is only through critical mass, awareness and persistent legal, political and emotional struggle that the capitalist forces behind the Balkan hydropower boom and its bulldozers can be kept at bay. One of the key limitations for the Balkans campaign presently (and part of the larger problem) is the marginal space the Balkans occupy on the mental map of European policy-makers and society at large. The weekend in Belgrade was an opportunity to gather and exchange creative strategies for collective struggle, and brought forward some innovative ideas for how to raise awareness about the ecological value of the Balkan Rivers and the controversial development plans. Most importantly, the activist gathering showed that the will, determination and networking power to collectively deliberate on the kinds of environments we want to live in is there.

More information on the Balkans dam boom can be found here, here and here (last one in German only).

Group photo during the Balkan River Days, with a message of support to the “Ne da(vi)mo Beograd” initiative that opposes commercial waterfront development in Belgrade. Photo by Anze Osterman/Leeway Collective.

capitalist forces? lol