By Melissa García-Lamarca and Santiago Gorostiza

A walking tour exploring some of Berlin’s radical history opens the door to reflections on how sewing rebellious histories of urban spaces can inspire our imagination of radical futures.

The centre of Berlin, Unter den Linden, is a hotspot of history, the site of three revolutions and the rule of the Nazis. Until 1800, what is now the heart of Berlin – the Mitte district – was the extent of the entire city. But with the development of capitalism in 1830 the city transformed rapidly, doubling its population every 20 years, a growth that spurred rapid and dramatic changes.

By 1918, Berlin had almost reached two million inhabitants and stood as the largest German city, with most migrants flowing in from regions east of the city like the province of Silesia (Prussia) and Poland. Migrants poured into eastern Berlin where people worked like dogs and lived in terribly crowded conditions, while the rich rested their bones in west Berlin. The class and spatial development of the city during this period were intertwined in part due to winds carrying pollution from west to east, reminiscent of the patterns of expansion of other cities like London or Manchester, as told by Friedrich Engels in “The Condition of the Working Class in England.“

Organised by Berlin Subversiv, the walking tour we took during one of our final ENTITLE courses was led by the labour sociologist turned tour guide Win Windisch. The tour started at the main entrance of Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, in front of which the most upheaving moments of German history unfolded, including the Revolutions of 1848, 1918, and 1989. One of the most notable alumnus of Humboldt Universität is of course Karl Marx, whose famous quote “the point is to change it” is engraved in large, golden letters on the staircase walls of the foyer.

One part of the tour focused on the 1918 revolution, a time when workers’ and soldiers’ councils had started to flourish in the last days of the First World War. An underground movement in the factories led by metal workers was a critical backbone of the revolution, culminating in a march on 9 November to central Berlin that forced the declaration of the German republic and the resignation of the Kaiser. Revolutionary speeches unfurled across two lines: one, by Karl Liebknecht, pushing for a new type of economy based on direct democracy with workers’ councils, and the other, lead by Phillip Scheidemann, pressing a social democratic solution to establish order. It is interesting to reflect that as the latter won out, preventing radical changes, the path was opened up to the emergence of the national-socialist party and subsequently Nazi rule.

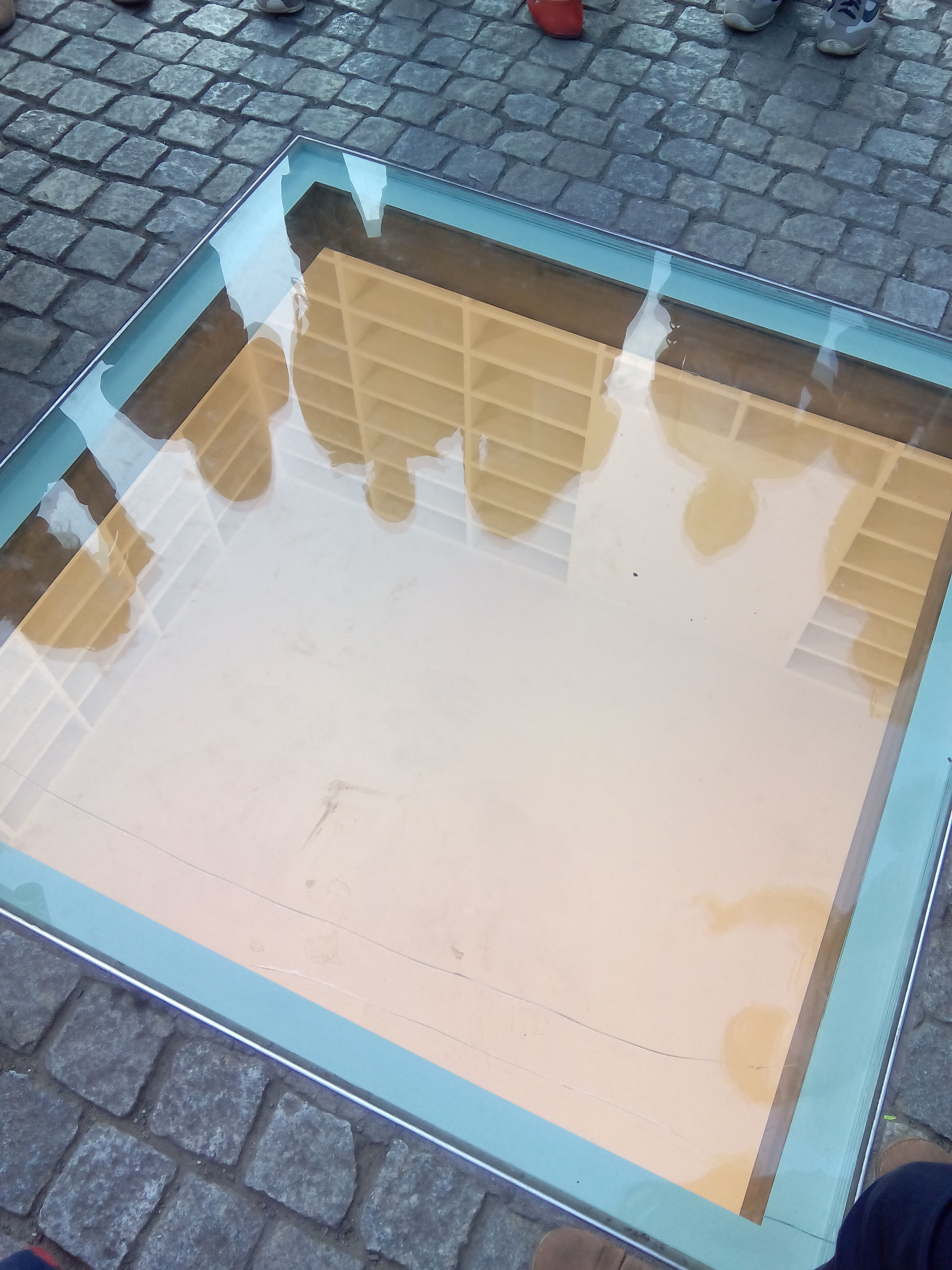

We also visited a site that is a key ideological marker of Nazism: the May 1933 book burning, signaling the end of the freedom of opinion in Germany. This took place in front of the Humboldt University’s former main library, where academics played a welcoming role and 5,000 students marched in the procession. The elite breeding that made up the university environment at the time meant that conservative ideas were in free flow, and these elites supported and furthered the Nazi’s belief that “people need to know their position.” As most of us are more or less deeply embedded in academia, this provoked important reflections on how universities have been, and (unfortunately) in many cases still are, key sites of conservative thinking that ultimately seek to preserve and extend the status quo. Our tour guide also noted that “what is striking, is that many students walk past and over this underground monument daily, without knowing the history behind it, or what the monument stands for”. Clearly then, there is need for learning one’s underground history, and the work our tour guide does can be instrumental and influential to bring Berlin’s underground history to the fore.

Book burning memorial at Bebelplatz. Photo: Santiago Gorostiza.

“Stepping out of the straight jacket of academia…”

Beyond these brief histories, the walking tour highlighted the narratives that are hidden or even erased through urban development. Far from nostalgic accounts of defeats and failures, the stories of different historical struggles can be a source of inspiration for the imagination of radical futures. By narrating stories about specific places that are connected by physically moving to the key urban sites and spaces where these narratives unfolded decades or centuries ago, activists and urban city guides can sew alternative stories to the ones systematically repeated by mass tourism.

Aware of the importance of such stories, guides, artists, activists and historians from all over the world gathered in Barcelona in 2012 to create the international History From Below network. Win Windisch, our guide from Berlin Subversiv, was one of them. From bike history tours in San Francisco to collaborative map-making from Buenos Aires, the network brings together a surprising variety of radical approaches to history. Their members envision history “as subculture and self-organised do-it-yourself practice” and challenge the predominant role of professional historians. Since 2012, they organise a public conference which, under the name of Unofficial Histories, calls for discussing “how the past is used and presented in society, from the university and public arenas, to popular culture and everyday life”. The 2015 conference was celebrated on the very same days that our tour took place at the International Institute of Social History, in Amsterdam. You can find the programme of the conference here.

After wandering through different historical moments and sites of both revolution and repression in Berlin, it was hard to not consider how more insidious processes of dispossession are currently underway across the city – for example, capital led gentrification and displacement, called class war by some – and what this means for urban struggles for equality and just socio-ecological futures. But this is material for another post. At the end of the tour, our massaged minds and feet were reinvigorated as our guide bid us farewell with a parting phrase: “I hope you remain rebellious.”