by Carlos Tornel

In Ancestral Future, the Brazilian Indigenous leader and philosopher Ailton Krenak recounts the story of the Maxakali community, an Indigenous group from the eastern rivers of Brazil. He describes how, despite being dispossessed and forcibly removed from their land, the Maxakali retain a remarkable ability to recall and narrate the presence of the living beings—animals and plants—that once shared their territory even though they no longer share it with them. Krenak emphasizes that this act of remembrance is more than nostalgia; it is a way of remaining rooted, or sustaining the experience of place. Even as modernity expands, imposing an abstract, homogenized notion of space—a void to be filled with ‘development’—the Maxakali resist this erasure by preserving their connection to nature through storytelling and memory. Their ability to inhabit, even in displacement, serves as a powerful testament to how communities, sometimes against all odds, retain their dignity, their sense of belonging, and their past and future as living, continuous realities. I often find myself returning to this thought as a profound example of resilience in the face of development and its multiple faces of dispossession.

The development enterprise, now 76 years old, has been remarkably effective not in solving poverty, but in producing and perpetuating it. As Majid Rahnema argues in The Development Dictionary, the term had multiple meanings before January 20, 1949. Poverty could be a voluntary choice, a form of exclusion from the community, a public humiliation, or a lack of protection. It was only with the expansion of industrial and mercantile economies that poverty became redefined as the opposite of ‘rich’ or a measure of wealth —a condition of material deficiency requiring intervention. The proposed solution, of course, was development— understood as the systematic deployment of industrial production, a wage-based economy, and the positivist advancement of technology and scientific knowledge, concentrated in the hands of professionals and experts. This logic did not simply enclose the means of production or subsistence, as Marxist thinkers might have predicted; it went further, creating a system of dependencies that rendered people perpetually in need of development itself—an alienating force that reshaped entire ways of being into something incomplete, always lacking, and requiring external intervention. Despite this there are many grassroots, autonomous and alternative movements resisting and creating alternatives to the development enterprise.

For five days in February, I had the privilege of joining land defenders, grassroots movements, Indigenous Peoples, and communities from 20 countries across the Global South in Port Edward, along South Africa’s Wild Coast, to discuss radical democracy, autonomy, and self-determination. Hosted by the Global Tapestry of Alternatives, the Academy of Democratic Modernity, the Amadiba Crisis Committee, and the Pan African Ecofeminist Alliance WoMin, this gathering was more than an exchange of ideas—it was a convergence of struggles, lived experiences, and collective visions for autonomy. Despite the participants’ diverse backgrounds, languages, and contexts, a striking commonality emerged: a clear and resounding rejection of the development enterprise. Over the past 40 years, what began as a slow erosion of the means of subsistence has escalated into a full-scale war against it. Development, far from being a means of upliftment, has proven to be an economic and political project of alienation, dispossession, and enforced dependency—disrupting ways of life, dismantling communal autonomy, and deepening systemic inequalities. This gathering reinforced that resistance is not just about rejecting this imposed model, but about reclaiming the power to define and create our own futures.

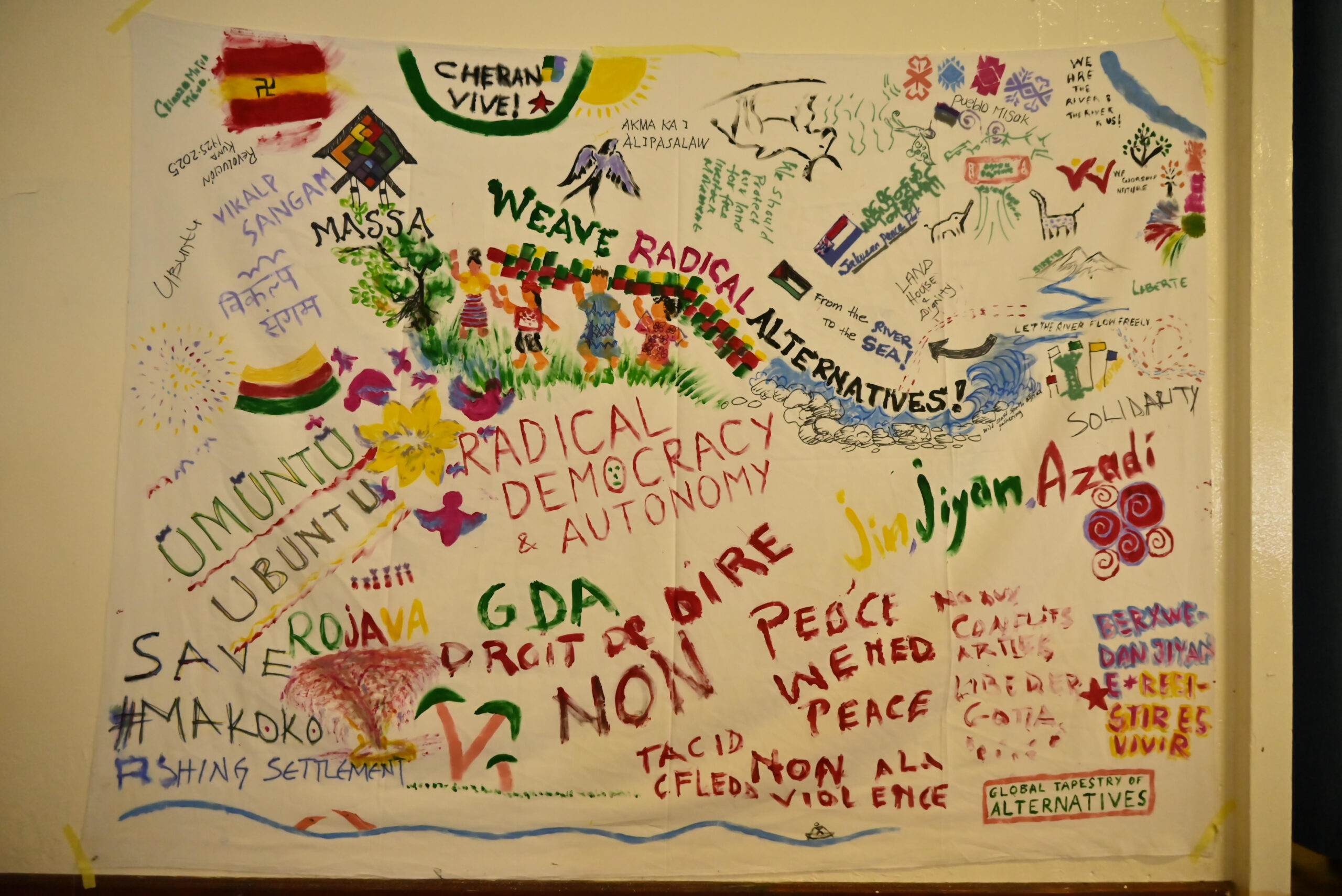

Participants at the inauguration of the Global Confluence on Radical Democracy, Autonomy and Self- determination’, Port Edward, South Africa, 2-6 February 2025.

What is the crisis we are facing?

Communities and grassroots movements striving to maintain their autonomy and practice radical or direct democracy are facing unprecedented challenges in an era of extreme inequality, shaped by centuries of exploitation and dispossession. The intersecting crises of climate collapse, economic inequality, and rising authoritarianism are intensifying new forms of oppression and violence—particularly against the ‘poor’ and marginalized communities produced by decades of development policies. The state has become central to enforcing the disciplinary, counterinsurgency, and social engineering technologies necessary to sustain capitalist extraction. At the same time, the far right has weaponized capitalism’s crisis to push liberal democracy toward xenophobia, racism, and hatred which serve as tools to entrench elite and corporate-driven forms of extreme neoliberalism.

Meanwhile, leftist and progressive governments have largely resigned themselves to crisis management, acting as administrators of capitalism’s systemic failures rather than challengers of its logic. In countries like Mexico, the rapid expansion of militarization and state-deployed social engineering technologies reinforces what Leanne Betasamosake Simpson calls the extraction-assimilation system—a model in which people, their knowledges, nature, and the more-than-human world are treated as resources to be rendered extractable. As these dynamics unfold, grassroots resistance remains critical, not only to oppose these structures but to reclaim autonomy and sustain alternative ways of being and relating beyond the confines of capitalist and state control.

At the heart of these struggles is a demand for more than rights or state recognition— a framework that ultimately reproduces condescending forms of hospitality, tolerating otherness while reinforcing systems of alienation through participatory and democratic mechanisms. Instead, these movements are fighting for radical autonomy. Paraphrasing the rich debates and discussions held during the meeting, the prevailing sentiment was clear: “We cannot ask or wait for the state to act. If we did, we would be long dead before development arrived. Instead, we must build, reclaim, or maintain systems of self-governance to sustain our territorialities.”

The concept of territory was central to this understanding. Participants emphasized that land and place are not only essential for constructing autonomous systems of self-determination and radical democracy, but also embody deep historical, epistemic, and ontological relationships—connecting people to nature and to ways of being that precede and resist capitalist modernity.

The meeting reinforced what many have long argued: the race toward development is a race toward deeper dispossession. This is not just about the extraction of resources; it is an increasingly violent system that enforces total alienation from the means of subsistence. As Ivan Illich warned, development is a war on subsistence—where in the logic of capitalism, economy becomes synonymous with scarcity. The crisis we face today is not merely economic or political, it is existential.

Participants of the Global Confluence on Radical Democracy, Autonomy and Self- determination’ in a visit to the Xolobeni Community, hosted by the Amadiba Crisis Committee (AAC). Photo by Ashish Kothari.

This ‘modern’ state system, as Ailton Krenak argues, has become highly proficient in the production of poverty and perpetual precarity by alienating people from their lands—whether through direct displacement or the slow contamination and degradation of their territories— forcing them into urban peripheries where no connection to autonomous livelihoods remains. Even institutions like the World Bank have acknowledged this trend, which is particularly visible in countries like Mexico, where nearly two thirds of those classified as poor under modern definitions live near or in cities. The state, in its contemporary form, does not function as a protector but as a facilitator of dispossession, offering ‘solutions’ that ultimately serve corporate and elite interests at the expense of communities.

How are communities responding?

While the term radical democracy is not one that communities use to describe their own decision-making processes, participants in the meeting in South Africa emphasized that autonomy and self-determination are not about seeking state recognition, but about reclaiming the power to govern and sustain life on communities’ own terms. The ‘radical’ in the term points towards the multiple struggles at the grassroots where alternatives are actively breaking away from liberal institutions and the extractivism that manufactures dependence. The response to this crisis is not uniform, but it is clear: grassroots communities are rejecting formal education, healthcare, housing, transport and other expert-led systems that produce “needy” individuals. Instead, they are building self-sufficient networks of mutual aid, reclaiming food sovereignty, energy autonomy, traditional healing, learning and collective (re) inhabitation among many other direct challenges to capitalism and development’s monopolization of basic needs.

Many movements are resisting so-called “green transitions,” which disguise new forms of extraction under the banner of sustainability and climate change ‘mitigation’ and ‘adaptation’. Others are directly challenging the legal frameworks that reduce collective rights to manageable, individual, co-optable categories, reliant on expert, state or market produced services. Paraphrasing what some of the participants argued: “collective and Indigenous peoples rights cannot be limited to human rights. These rights are based on the rights of nature, on our relationships with territory and place, and on our capacity to determine how we relate to and in these places.”

This response, again is not homogenous, but entails a radical plurality of actions, struggles and movements reclaiming dignity: building radical alternatives that are rooted in creating a sense of place and communitarian entanglements that redefine a sense of value produced through a commonly defined good life.

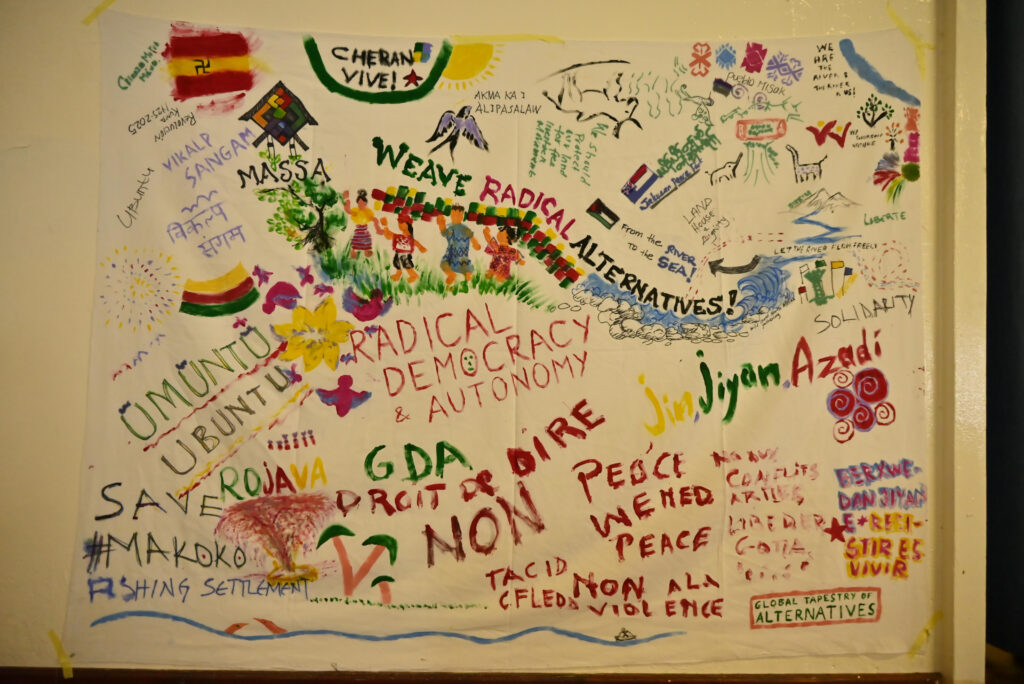

A tapestry of alternatives and radical democracy, made by participants of the Global Confluence on Radical Democracy, Autonomy and Self- determination’. Photo by Ashish Kothari.

The gathering highlighted the vital role of grassroots struggles in advancing radical democracy and emphasized the urgent need for academia, NGOs, and civil society to reconsider how they engage with these movements. Too often, these institutions, even with good intentions, align with the development agenda by treating knowledge as extractable and transferable, reinforcing the same systems of power that communities resist. In contrast, the struggles represented assert that knowledge is not the exclusive domain of universities: communities possess their own theories and political visions, rooted in everyday resistance and collective traditions.

The central question is no longer whether radical democracy is possible, but how to sustain it in a world bent on its erasure. This calls for a fundamental shift: from supporting movements through hierarchical models to co-creating with them in ways that dismantle the extractive-assimilation system. The struggle for autonomy is not merely opposition to development but a process of rebuilding social fabric through mutual aid, reciprocity, and self-determination.

As the confluence in South Africa demonstrated, these struggles are not isolated—they are interconnected nodes in a global movement toward radical democracy. As several of the participants expressed: “We should no longer seek recognition from the state, but from each other.” From Indigenous communities defending their lands against extractivist projects, to urban collectives reclaiming the capacity of decision making from the state, what emerges is a vision of autonomy built on global solidarity that moves beyond reform to the active construction of new worlds. Autonomy and radical democracy thus cease to be abstract concepts: they entail the lived experiences of those who refuse to be governed and ‘developed’.