By Luca Scheunpflug and Dennis Schüpf

The Fehmarnbelt, the strait between Germany and Denmark in the Baltic Sea, is the scene of the construction of one of Europe’s largest, yet controversial, infrastructure projects. This photo essay reveals the project’s impacts on the existing socio-ecological fabric of the coastal region, and local forms of resistance.

Isabel Arent and Hendrik Kerlen, central figures of the local resistance, are carrying a wooden blue cross nearby the Fehmarn side of construction. The blue cross, a symbol of resistance, is called ‘Andreaskreuz’ and originally entails a rail traffic sign.

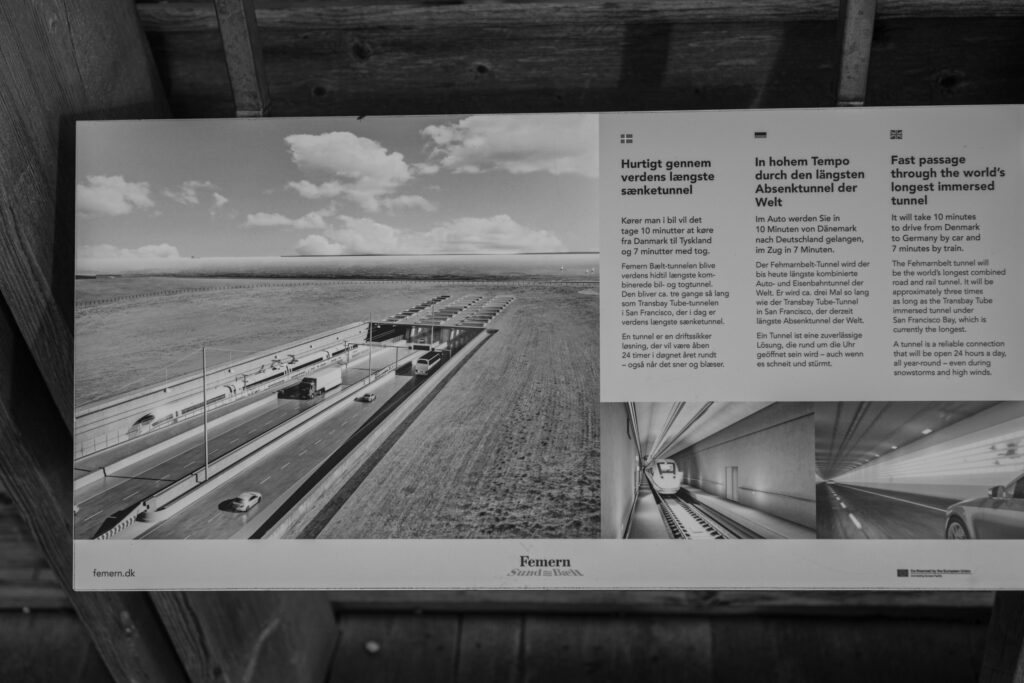

In the coming years, the island of Fehmarn on the northern German coast of the Baltic Sea and its local communities will witness drastic socio-environmental impacts from one of the European Union’s largest infrastructure projects: a planned immersed tunnel, which will connect the island in Puttgarden at its narrowest point over 18 kilometers underground via the so-called Belt, with the Danish Island of Lolland.

Explanations, images and futuristic vision of a completed Fehmarn belt at the Danish construction site: “Fast passage through the world’s longest immersed tunnel”.

The massive work harbor is constructed on the Danish side at Rødbyhavn. The harbor play a key role during the construction phase. It is built with the aim to deliver raw materials, such as stone, sand, gravel and steel by sea to the construction site.

Planned and financed by Denmark and accompanied by large-scale advertising campaigns on both sides of the border, the project is claimed to be a brilliant merit of engineering and an essential factor for economic prosperity and European cohesion. Arguably, it will significantly reduce travel time between the metropolitan regions of Hamburg and the Scandinavian countries, by making individual car or highspeed train travel possible. Following the planners’ line of argumentation, this is intended to boost the European domestic economy, as well as regional markets and small businesses.

Viewpoint established by the Danish state company A/S. Sand and gravel from the nearby seafloor has been dredged up resulting in a newly formed landscape during the construction phase. In the background the Scandlines Ferry is transporting people and cars along the envisioned tunnel site.

A dredger is digging up sand and thus adding to the hill of dredged seafloor on the Fehmarn side.

Besides the eager promotion of the project, there has been considerable opposition against the construction of the tunnel from a broad alliance of civil society organizations, local chapters of progressive political parties, trade unions and nature conservation organizations on the German side. On the Danish side, the project is not only actively supported by politics and business – even environmental NGOs rate the project as positive. The predominant political support among most parties and experience from previous projects as well as fewer critical voices towards politics in general, forecloses resistance there. In this photo essay, we show how the injustices of ‘futuristic’ infrastructure developments are legitimized through depoliticizing and marginalizing growth discourses of modernization and economic prosperity. We also highlight the resistance of organized communities and environmental defenders, from the subjectivities of local residents living on Fehmarn.

This resistance confronts the dominant growth discourse with the devastating consequences of the project on the way of life of the island of Fehmarn. The livelihoods of local communities are mainly centred around natural resources: fisheries, traditional agriculture and individual small-scale tourism embedded in a rural landscape. The intensifying exploitation of coastal resources, increasingly vulnerable to climate change, merits special attention. The Baltic Sea remains no exception: the profit-oriented degradation has turned it into a sea in precarious ecological condition.

A seawall made of stones is constructed as part of the work harbor on the Danish side.

Hendrik Kerlen, local resident and Chairman of the “Action Alliance against a Fehmarnbelt Fixed Link”.

The Fehmarnbelt tunnel represents an unprecedented infrastructure project in the European context, in terms of construction methods and materials, as well as in its socio-environmental impacts. It has already caused unrest and conflicts between local groups such as farmers, small tourism businesses and fishermen, and international construction companies and investors, showing deep injustices.

While the economic and mobility benefits from faster connection will be concentrated in the metropolitan regions of Hamburg and Copenhagen, the local community will bear much of the costs from degraded ecosystems and landscapes. These interests are left behind. The dialog forum proposed by politicians and the Danish public planning company Femern A/S was intended to prevent conflicts between various stakeholders with the goal to develop joint solutions. Yet the forum in fact only offered an illusion of participation, with limited opportunities for true dialogue or the community’s intervention and influence in project planning. More critical groups left the forum due these limited possibilities.

Advertisement of sustainability in the context of the Fehmarnbelt tunnel set up at the Fehmarn construction site by the operating Danish company Fehmarn A/S.

Viewpoint on the dredged seabed where before you could see the sea.

These injustices largely occur on the basis of lack of recognition of local perspectives and their values. It became apparent that the cultural aspects of the communities, characterized by a rural-agrarian and normative-emotional connection to the coast, played no role in the project planning phase, nor access to decision-making.

Within multiple political and juridical decisions, the discourse of accelerated economic benefits for the Scandinavian region and Europe facilitated by the tunnel, has legitimized project planning, decision-making and implementation, ignoring the impacts highlighted by multiple civil society organizations. The central actors here have been the Swedish and Danish governments. From the protesters’ point of view, these governments are representing corporate interests. This is a fundamental aspect of the European Union’s neoliberal policies: on the one hand equating economic growth with European integration, and on the other, over-representing corporate positions.

Advertisements for new apartments are set up with a “Belt-View” next to the construction site of the tunnel on Fehmarn.

This economic growth discourse relies on an overemphasis of predicted long-term benefits that remain vague and fuzzy. Fears of declining numbers of tourists and implicit economic losses for the local community are mostly externalized to the future, while ironically promising an increase in tourists due to the “effective” connection to Scandinavian countries and the South of Germany. This contrasts with the particular type of tourism on Fehmarn, which is nature-oriented and based on small and family business organization. The growth discourse has left no room for this alternative perspective on regional development. Similar conflicts can be seen in other coastal regions of Germany, such as in the gentrification on the island of Sylt and over-tourism on Rügen.

A traffic sign pointing to various sites of the Fehmarn belt construction on the Danish island of Lolland.

A second dominant discourse that complements that of economic growth is “sustainability”. Here, the focus is primarily on the improved train connection including high-speed links to be created through the tunnel. This is intended to strengthen the “switch to rail” as “green mobility”, promoted by the German federal government, but also by the EU in the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) initiative.

Vehicles in line waiting for the onboarding on Scandline Ferries to travel from Fehmarn to Denmark.

On deck of the hybrid-ferry of Scandlines.

In contrast, the climate impacts of the tunnel are hardly discussed at all. While high-speed rail is promoted as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the largest quantities of such emissions are hidden in the production of necessary construction materials such as steel and concrete. This sustainability narrative may explain why the project has not been a focus of national and international environmental campaigns around climate justice, unlike other projects such as the expansion of the open-cast mine in the Rhineland Lützerath (see here and here).

Monument at the cemetery of honor for the dead of the Cap Arcona and Thielbek disaster during the Second World War. The planned route of the railroad belt connection through the hinterland of Schleswig-Holstein is to be carried out here. The monument will be affected by the project implementation.

Despite the court rulings that legitimized the actual project, activists are still trying to fight against partial aspects such as the above-mentioned rail connections both legally and in the public debate. Without supportive problematization and mobilization from civil society and politics, however, this will be a difficult undertaking. This text therefore aims to encourage greater awareness and critical reflection on such megaprojects in order to question powerful narratives of progress and bring ecological and post-growth positions more strongly into the discourse.

Sign of resistance in the colors of the Fehmarn Island – A blue Andreaskreuz.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Luca Scheunpflug is a political ecology researcher and independent writer. He was trained in International Development Studies (M.A) and is currently researching environmental justice movements and the politicization of infrastructure and planning.

Dennis Schüpf is a freelance documentary photographer and environmental justice researcher. He has a degree in International Development Studies (M.A), and works at IDOS (German Institute for Development & Sustainability) as doctoral researcher investigating shrinking coastal commons, in particular sediment flows, in the context of local adaptation to environmental and climate change.