By Jevgeniy Bluwstein and Rebecca Rutt*

The Flint Water Crisis led to different forms of grassroots activism demanding political accountability, transparency and redress. Yet residents’ experiences, and their needs and demands in response to the crisis, were and continue to be suppressed in multiple ways.

Source: BET.com.

Since 2014, the city of Flint, Michigan, has been at the centre of what has become known as the Flint Water Crisis. After an unelected technocrat decided to switch Flint’s water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the corrosive Flint River, and neglected corrosion control, lead started to leach from Flint’s aging water pipes into the city’s water supply. In response, Flint residents assumed a central role in demanding environmental justice in the form of political accountability and meaningful political and technical solutions.

In a recent paper published in the journal Environmental Justice, Quests for justice and mechanisms of suppression in Flint, Michigan, we explore the mechanisms of suppression at work in obscuring Flint residents’ advocacy and activism. Drawing on insights by Flint residents and critical observers, we shed light on the roles of the public sector, emergency management, the media and academia in reproducing these mechanisms of suppression.

Problematic roles of public authorities, media and academia

Public authorities at local and state level failed Flint residents in numerous ways. Some respondents experienced paternalistic and misogynistic treatment in public hearings. For example, women who voiced their concerns were called “hysterical”. One respondent recounted how in a public debate in early 2015, a Flint city councillor asked if she “was on her period”. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality also tried to discredit residents’ self-organised water testing campaigns – which had been conducted under the scientific supervision of Virginia Tech experts – by presenting test results from strategically sampled areas without lead plumbing.

Virginia Tech professor Marc Edwards shows the difference in water between Detroit and Flint. Photography by Jake May, The Flint Journal. Source: National Geographic.

Residents described a national “media blackout” in much of the first year of the crisis. Until early 2015, there was an almost total lack of coverage by mainstream US media outlets. When the media giants finally took note of Flint, they would “parachute” in and out.

To counter simplistic media accounts, residents turned to social media to tell their own stories and gain control of the narrative. Michigan governor Rick Snyder strove to frame the crisis in technical terms, as a chain of unfortunate events, failures and unintended consequences- a framing that was upheld and disseminated by some mainstream media outlets. Many Flint residents and critical observers reject this narrative as undermining their demands for political accountability.

To some residents, academic institutions also contributed to the obscuring of what matters in Flint. Referring to a proposed university-led survey on people’s willingness to move, a respondent pointed out that “UM [University of Michigan] researchers are researching stuff that nobody asked for […] They are doing research to further their careers. It’s not help.” Critical observers highlight that academic dependency on funding and Flint’s reputation constrain research and activism agendas of local and state-level academic institutions vis-à-vis the water crisis: “..it’s a ‘don’t find bad stuff’ mentality.”

The role of emergency management, or Flint as a canary in the (neoliberal) coalmine

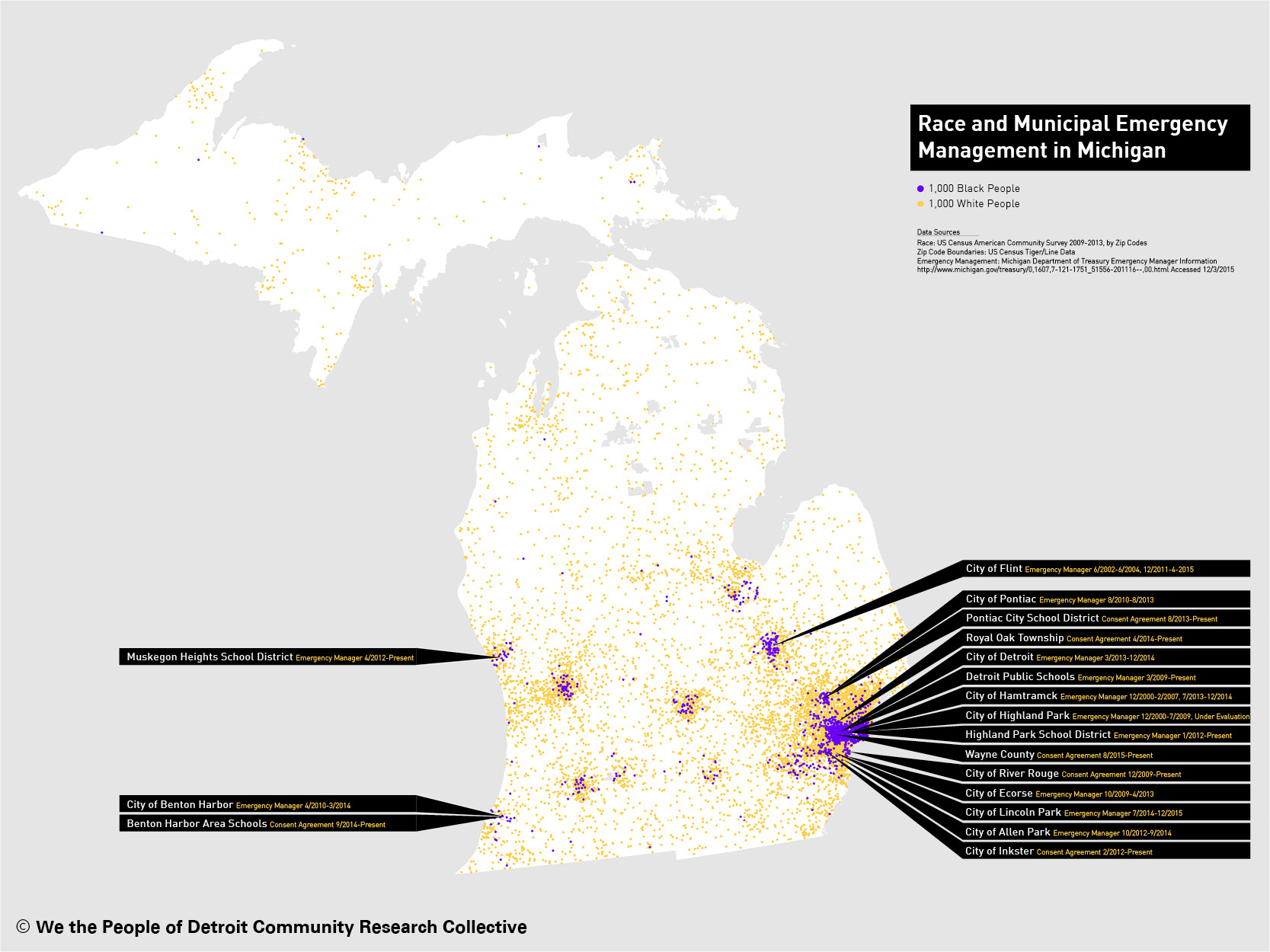

Flint is a majority black city in a state whose demographics and economic and political establishment are predominantly white. In a continuation of the historical expropriation of black communities, emergency management was introduced in black communities across the state of Michigan in recent years as illustrated in the map below. Emergency management suspends the powers of elected city councils and mayors and undermines established mechanisms of democratic representation. Residents see emergency management as an “imposition of autocracy” and a “crisis of democracy”. Scholars similarly refer to it as a “democracy deficit”, pointing out that disenfranchisement through emergency management is particularly problematic in that such takeovers inherently target already weakly-franchised populations.

Against this backdrop, the Flint Water Crisis clearly did not emerge from thin air. It is a reiteration of longstanding racialized patterns of social exclusion, political fragmentation and disenfranchisement, as has been underlined by environmental justice scholars Sadler and Highsmith and Mann. In this context, emergency management intensifies capital accumulation through further outsourcing state functions to the private sector, a process that a UM-Flint faculty member described as, “the state of Michigan looting the public sector”. As we detail in our paper, emergency management also has another important function. It contributes to suppressing people’s demands for justice and accountability by privileging market logics over health concerns, blaming disenfranchised communities for the perceived inability to govern themselves, and promoting depoliticized narratives of progress and prosperity.

Clearly, public authorities, especially at the state level, are interested in ending the problem as an unfortunate cascade of technical failures. Flint’s political and economic elites are concerned about Flint’s reputation as a city in economic decline. Academic and scientific endeavours take place under structural constraints that encourage technical solutions and inhibit critical queries. The media continues to serve multiple interests, some entangled in financial incentives, some keen to retain neutrality that ignores the unequal power relations at play, thereby further reinforcing these differences.

An image from the state of Michigan’s “Pure Michigan” campaign. Source: regan.com

The big paradox is that the state of Michigan is surrounded by the Great Lakes, the “planet’s largest bodies of freshwater”, as the state ‘Pure Michigan’ campaign points out. While communities like Flint are denied clean water, the state grants virtually free access to public water resources for commercial use by private companies such as Nestlé. This led a respondent to describe the state as “ground zero for water wars”. Flint residents are aware of the political economic and historical embeddedness of the Flint Water Crisis: “Flint is a canary in the coalmine: if it can happen in Flint, it can happen in other places too”.

* Jevgeniy Bluwstein is a PhD candidate in political ecology at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. His research interests include political ecologies and geographies of conservation and development interventions, as well as resource governance and land control.

Rebecca Rutt is a research associate at the University of East Anglia, UK. Her research and teaching interests engage with issues of concern to political ecology, environmental justice, and feminist inquiry. Rebecca spent autumn 2016 as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Michigan, during which the work above was undertaken.