by Alexander Dunlap, Mariana Riquito, Bojana Novaković & Darko Lagunas Leon

A thorough debunking of the recent documentary Europe’s Lithium Paradox, which leads to broader questions about academic platforming and the impoverished debates within sustainability institutes.

On December 2, 2021, the European Parliament held a PETI Hearing, “Environmental and Social Impacts of Mining Activity in the EU.” During the hearing, Alexander Dunlap warned that the Horizon 2020 grant scheme “has and continues to fund ‘soft’ counterinsurgency initiatives designed to enforce mining and industrial production – regardless of the ecological and climate catastrophe.”

Almost four years later, on November 25, 2025, a Horizon Europe-funded film was shown at the Pathways to Sustainability series, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Since 2021, the European Commission passed the Critical Raw Materials Act (2024) and President Ursula von der Leyen exclaimed: “we cannot function without critical raw materials.”

Europe’s Lithium Paradox (2025) was introduced by Dr. Peter Tom Jones. The film demonstrated high-production quality: it mimicked the journalistic format by talking to mining advocates and critics and, most of all, emphasized geopolitical competition with China and Russia as well as the challenges of meeting consumer electronic demands and the looming climate catastrophe. Most of the documentary, however, was company public relations representatives presenting their goals and ‘facts,’ and dismissing all opposition as ‘misinformation’ or not based on scientific evidence.

At the Pathways for Sustainability event, the movie had a panel composed entirely of materials’ scientists. Even though, as audience members, we voiced our concerns and debunked some of the lies present in the film, our comments were met with Dr. Jones’ bragging to the audience about the film’s positive reception in other venues; expressing contempt for post/degrowth; or simply ignoring our evidence-based points. When asked about water contamination by another researcher, Dr. Jones dismissed such worries, saying that the EU classifying lithium as a toxic agent “is shooting ourselves in the foot” and exclaimed: “Let’s be honest, water is also toxic” to deflect from the issue.

We contend that platforming this film attempts to undermine the communities depicted in the documentary and to advance extractive industry objectives. We believe in the importance of fostering honest academic dialogue between disciplines and the public, but Europe’s Lithium Paradox has departed from the Pathway to Sustainability series stated aims. Instead, we witnessed a propaganda film that requires thorough debunking to reveal the misinformation and manipulation it engages in.

Mining Industry Propaganda

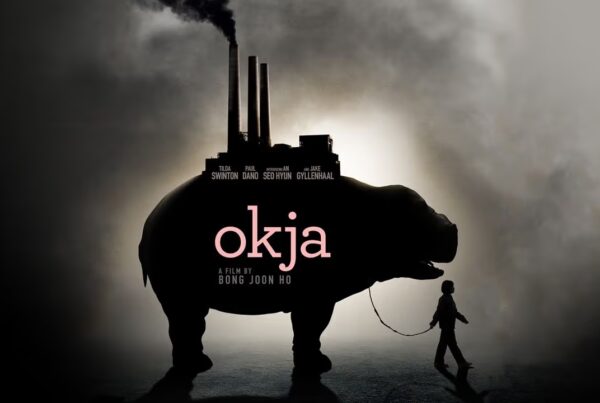

The framing of the film, while concerned about geopolitical competition and climate change, does not question growth imperatives in electric mobility, high-technology and other industrial sectors. The film upholds the myths of “decoupling,” “green growth” and eco-modernism, which studies demonstrate have little-to-no empirical basis (1, 2, 3, 4). Instead, mining, electric vehicles, heavy industry and consumerism are positioned as “green” and unquestionable goods.

The fossil fuel versus low-carbon dichotomy is foundational to the film, while ironically touring lithium recycling plants, promoting prospective mines and lithium refining that require enormous amounts of energy from a mixed energy grid (e.g. nuclear, coal, oil, natural gas & lower-carbon technologies).

The film operates in generality, failing to ask questions outside the company public relations scripts. In doing so, it uncritically showcases the perspective, voice and concerns of the lithium industry.

Still from “Europe’s Lithium Paradox”, 00:24:22

It implies that Europe needs to (re)mine its own lands – opening old and starting new mines – to become supply-chain self-sufficient. While the film shows (25:10) that Europe only requires “10% mining; 40% refining; 25% recycling” domestically, it ignores the mining elsewhere and how energy and material demand will lead to cumulative greater advancement of global extractivism, and the unequal exchange this entails.

The narrative of the film plays to the fears of policy makers and the objective of the mining industry, going as far as to frame rural communities as ‘dangerous opposition.’ Similarly, the film is based on the overarching narrative that any opposition to mining is not based on facts. This portrayal, however, is inaccurate and detrimental to academic standards, which we explore in the case of Portugal and Serbia – the central communities featured in the documentary.

Still from “Europe’s Lithium Paradox”, 00:25:11

Portugal: Covas do Barroso

In the film, Dr. Jones presents his experience in Covas do Barroso as threatening and laments the “impossibility of engaging in a public dialogue.” During the event, as earlier on Linkedin, he went so far as to compare the village to the North Korea dictatorship. This framing is deeply misleading.

For more than eight years, the population of Covas do Barroso has consistently and publicly opposed the project, making extensive use of institutional mechanisms, including public consultations, legal actions, protests, petitions, and parliamentary hearings. To claim that “public dialogue” is impossible is therefore not an observation about the absence of dialogue, but a refusal to recognize a form of dialogue whose outcomes are inconvenient to pro-mining interests.

The fact that Covas’ inhabitants refused to engage in dialogue with Dr. Jones has many reasons. Despite being framed as ‘not in my backyardists’ (NIMBYists), local communities are deeply interconnected, and, in Covas, inhabitants knew about Dr. Jones’ previous misrepresentation of Serbia anti-mining movements; his tendency to frame Portugal and local communities as hostile; earlier insults towards mining critical communities; and founding an explicitly pro-mining academic-industrial consortia including the local project proponent Savannah Resources.

Moreover, no public local authority was contacted by the film crew about their intended visit to Covas do Barroso, which is a common and ethically responsible practice in academic, journalistic, or artistic research.

This reveals a broader extractive logic in the film’s methodology: the community is approached not as a political subject, but rather as an object to be instrumentalized for the movie’s end goals. In this framework, refusal is read not as a legitimate form of political agency, but as obstruction, hostility, or ignorance, reinforcing a narrative in which local opposition must be overcome rather than understood.

The film crew, and the KU Leuven financing consortia, consisting of industrial and academic partners, did not respond to earlier requests for transparency about their plans to capture footage regarding the film production in Portugal sent by MiningWatch Portugal six months prior to filming in Portugal to Dr. Peter Tom Jones, the EXCEED and LITHOS teams. Instead, the film crew came to Covas do Barroso accompanied by lawyer Thomas Gaultier, working for Savannah Resources.

This cooperation with the mining proponent, combined with the lack of prior information, and a 2020 scandal involving another EU-funded project in which the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) and geologist Dr. Toni Eerola – who accompanied Dr. Jones in Covas as a translator – played a central role as spokespersons for mining interests, led the people of Covas to decide not to engage with the film crew.

The film footage, then, was used without consent, hence the blurred faces, and is orchestrated to make the Covas resident’s threats against the film team seem unwarranted and unprovoked. Specifically, one community member, who was coming home from cutting hay with a sickle, was approached numerous times by Dr. Eerola, even though she expressed her refusal to appear in the film or participate in any interview from the beginning. This led to her strategic misrepresentation as a threat in the documentary, when actually it was her consent which was being violated.

The fact that footage appears in the final film demonstrates ethical disregard and confirms an interest in provoking a situation to advance Savannah Resources’ public relation interests in the film. We must not overlook the significant asymmetry of power and influence among the actors involved – whether Dr. Jones or the profit-driven mining companies – nor the history and track record of these companies, including the concealment of harms to advance their projects and the reliance on untested, hypothetical mitigation measures, as we briefly demonstrate below.

Still from “Europe’s Lithium Paradox”, 00:21:41

The documentary is framed around the idea that resistance is either misinformed or not backed by scientific evidence. However, the opposition to lithium mining in Covas stems not only from the existential threat of losing a UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO)-recognized sustainable place-based way of life, but also from technical and scientifically grounded assessments. Besides our own work (5, 6) detailing systematic manipulation and disinformation, the rejection of the ‘Mina do Barroso’ project is scientifically grounded, with numerous technical reports produced on the matter.

Hydrological geophysicist Prof. Dr. Steven H. Emerman has produced two reports in 2021 and 2023 on Savannah’s project. In his initial report, Dr.Emerman considered the design of the tailings dam “highly experimental” and an example of “reckless creativity.” After evaluating Savannah’s revised 2023 EIA, Dr. Emerman again recommended that “the proposed Barroso lithium mine should be rejected without any further consideration.”

Similarly, Dr. Douw G. Steyn, Professor Emeritus at the University of British Columbia, produced a report on air quality, in which he points out serious flaws and omissions in the assessment that led to the favourable Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) issued in May 2023. Dr. Steyn highlighted the inadequate characterization of air quality in the project implementation area, noting the unclear modelling of harmful particle dispersion that was unable to predict the negative impacts of the project.

As the documentary unilaterally depicts the mining company’s side, these technical reports reveal a significantly different picture: one of unresolved structural risks, insufficient environmental modelling, and a systematic downplaying of potentially irreversible impacts.

Thomas Gaultier says that the mining project is “not at all incompatible” (8:40) with the classification of the Barroso region as World Agricultural Heritage and as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), attributed in 2018 by the UNs FAO. This is a lie. The Portuguese Environmental Agency (APA) recognized explicitly, in its EIS, that:

“the combination of these direct and indirect impacts, including residual impacts, along with the potential cumulative impacts imposed by the high pressure of projects on the study area, could compromise the World Agricultural Heritage classification awarded to the Barroso Area by the FAO. It is also considered that there is no compatibility or relevant possibility of integrating the present project into the landscape of the territory, especially considering its classification as a GIAHS site.”

In February 2024, the Portuguese Public Prosecutor issued an opinion calling for the annulment of the EIS due to several legal infringements. One of the main arguments was that APA was aware of the risks posed by the mining project to Barroso’s UN GIAHS classification.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, David R. Boyd, visited Covas do Barroso in September 2022, and wrote in his statement of conclusion that:

“large resource extraction projects that may violate human rights in the name of the green transition are antithetical to sustainable development (…) Open pit metal mining is illegal in some leading green nations, such as Costa Rica, because of environmental and human rights impacts. (…) Portugal deserves credit for leading the world in recognizing the right to a healthy environment (…) It would be difficult to reconcile this track record of leadership with approval of a massive open-pit mine in a community that is a globally recognized example of sustainable development.”

In sum, the Portuguese Public Prosecutor, the Portuguese Environmental Agency, and the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment admit that Barroso’s internationally recognized classification as an example of sustainable land use is incompatible with an open-pit lithium mining project.

The number of lies and manipulative framings in the Portuguese case is remarkable, and personally hurtful. Debunking all of the documentary’s assertions would require an entire research article. At its core, the documentary presents only the perspective of the mining company, while systematically misrepresenting local communities, who for the past eight years have exercised every available avenue to assert their right to say no.

Serbia: The Jadar Valley

Similar to Portugal, the depiction of lithium mining in the Jadar Valley is rife with manipulation. Claims as simple as, Serbia, “home to Europe’s largest and most valuable lithium deposit” (28:20) are lies.

The largest known lithium deposits in Europe are in Czech Republic and Germany. Likewise, the claim that the Jadar deposit contains 10% of global lithium reserves is also incorrect. USGS indicates that the lithium content in the Jadar deposit does not exceed 1.4% when total global reserves are taken into account (see also USGS, 2025: p. 111).

The largest lithium reserves from geothermal sources are located in Germany, primarily in the Upper Rhine Valley in the southwest of the country. From a chemical standpoint, this is the cleanest method of extracting lithium, incomparable to Jardarite extraction, which is being proposed in Serbia.

These reserves, however, are not without their own ecological, economic and technical issues. Germany has about 3% of world reserves, a figure which might be higher with the confirmed deposit containing roughly 43 million tonnes of lithium carbonate in the Altmark Basin in northern Germany. Serbia, on the other hand, has about 1.4%.

The film voiceover claims that, compared to other sites in Europe, “Jadarite is easier to process: it does not require energy-intensive thermal pre-treatment or extremely harsh chemical conditions. From a purely environmental perspective, jadarite processing would not pose more but fewer risks, according to metallurgical experts” (30:09-26), which is unequivocally untrue (as Dr. Jones should know better than anyone else).

Rio Tinto has never processed lithium, lithium has never been mined from under fertile, populated land, and, according to their own documents, it would require 1000 tons of concentrated sulphuric acid per day with an unknown amount of ammonia (extraction, processing and transportation) and 5000-6000 tons of water to dilute acid in the processing phase.

Eight Serbian scientists, from the Serbian Academy of Sciences (and elsewhere), have identified numerous high-risk ecological, social and technical issues with the proposed Jadar lithium mine.

This includes mine wastewater presenting a “high risk of endangering the water system on a wider scale” if released, “which, together with noise, air and light pollution, will endanger the lives of numerous local communities in the immediate vicinity of the mine, agriculture, livestock, beekeeping, etc.”

The researcher, moreover, “estimated total yearly CO2 emission from the Jadar project which would be in the range from 428 to 522 CO2eq/kt per year” and, like Covas do Barroso, is a “fertile agricultural area, and most importantly it will certainly destroy one of only three water-bearing areas in Serbia.”

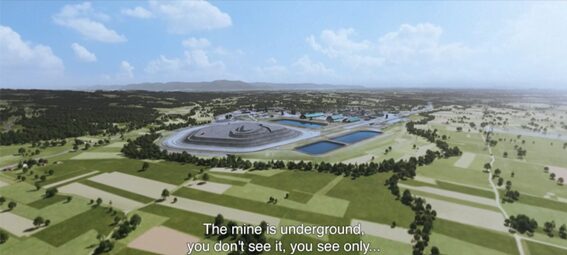

Still from “Europe’s Lithium Paradox”, 00:30:51

Still from “Europe’s Lithium Paradox”, 00:31:10 (undeclared Rio Tinto commercial footage)

Rio Tinto’s Public relations representative in Serbia, Marijanti Babic, in the documentary, brags about the low mine “footprint.” Babic explains, “We are talking about a surface area of 200 hectares above ground…The mine is underground, you don’t see it.”

While an enticing sales pitch, whether you only see 200 hectares (which is a questionable number given that the project includes a processing plant and two tailings dumps), this does not change the numerous geological, hydrological, air and chemical pollution issues that will emanate from the mine itself.

The film attempts to persuade viewers that, if you do not see the mine, it will not damage the environment nor its human and non-human inhabitants, which, from an ecological perspective, is absolutely incorrect. As the study above, by Dragana Đorđević and colleagues, showed, even test drilling for this project led to the release of excessive lithium, boron and arsenic pollution levels.

Later in the segment, Babic stresses the challenges Rio Tinto is facing in establishing the mine. Serbia has witnessed one of the largest environmental mobilizations in recent history, with citizens across the country organising protests, legal actions and public campaigns to oppose lithium mining and protect its vital ecosystems. This broad-based movement has shifted national discourse, pressuring institutions, exposing political-corporate ties and asserting environmental protection as a central democratic demand.

In discussing the protests, and the popular rejection of the Jadar mine, Babic explains: “We are struggling to see a fact-based dialogue and discussion about the merits of this project” (32:01). Aside from Rio Tinto sharing the same public relation consultant as Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vucic, the strength of the Serbian anti-litium movement has been ‘facts.’

The Serbian Academy of Sciences has held multi-day seminars (1), published books, and scientists have held panels and participated in televised public debates with company representatives. What’s more, when requesting to meet with social movement collectives, Rio Tinto representatives rescinded invitations when we asked that the meeting be recorded and that lawyers be present. “We’re committed to radical transparency,” Babic claims — yet her signature appears on Rio Tinto’s official submissions to the Ministry of Mining requesting that the public be denied access to all project information in the event of Freedom of Information (FoI) requests.

Furthermore, the Serbian government has requested that the EU Commission does not make public their approval for the application for strategic status of the project. Finally, Jadar Project Resource reports have been given to the public heavily redacted, including the names and authors of the studies. This means the authors, and who authorised these studies remains unknown.

The anti-mining movement has been clear that it stands for no lithium and boron extraction in the Jadar Valley, no matter who is in power. The film, overall, sculpts misinformation to advance the pro-mining position, ignoring the popular opposition to the Jadar Valley mine that transcends social movements, the professional and academic classes.

Finally, the film talks about a political narrative shift in Serbia “from not in my backyard, to not in my country” (29:17), which is a lie. The Serbian anti-mining movement has never been “not in my backyard” (NIMBY), as the film claims, but has indicated wider political, ecological, economic and social concerns demonstrated in many ways.

One clear example is the Jadar Declaration, signed together with communities, collectives, and organisations from Portugal, Spain, Chile, France, Germany, and Bosnia. This declaration recognizes a common political struggle across Europe and Latin America, which seeks to find solutions to social, ecological, economic and climatic problems, instead of advancing high-tech capitalist extractivism. Europe’s Lithium Paradox purposely disregards repeated statements, knowledge and action to spin a simplistic and (neo)colonial narrative to acquire Serbian minerals.

Conclusion

While the documentary attempts to advocate for the “green transition” and the incomplete, if not faulty, accounting that reinforces it, the film uncritically celebrates the dominant position of extractive industries and the European Union’s competitive geopolitical interests. This narrative operates to the detriment of research and democratic social movements in Portugal, Serbia and others in solidarity with them across the world.

This film, while providing an exposé into the operations and imaginaries of extractive industries, also does a disservice to urban populations by refusing to critically assess the material, energetic and social costs of the dominant pathway of (ecological) modernist development.

We recognize the material and energy demand for the military sector which is invisiblized in the film, concealed by the rhetoric of geopolitics and economic competition. Platforming this film in Utrecht contradicts the stated goals of the Pathway to Sustainability series.

Considering the severity of social discontent, warfare, ecological devastation, and the unsustainable reality of economies and climate change, we need to begin having a more serious, rigorous and critical conversation about the current political, economic and social trajectories that industrial societies have created.

The origins of terms like “decarbonization” or the flippant ways “net-zero,” “sustainable” and “renewable” are still employed indicates a failure of academic critical inquiry and the dominance of industry public relations within the academy. There are profound issues related to profit maximizing companies, imperial states and the conflict of interests of universities, or departments within them, that deserve greater consideration and debate, if social and ecological sustainability are ever to be achieved.

(1) A recording of the full two day debate from 2021, which included members of the Academy, government, civil society and Rio Tinto can be found here.