By Byron Gálvez-Campos

In a global context of socio-ecological crisis and the need to address it in a just and transformative sustainable manner, the dialogue of knowledge emerges as a key instrument for rethinking interactions between human beings and nature.

The climate challenges that have triggered the need for a socio-ecological transition necessitate a critical approach to how and from where knowledge is produced, to present solutions that address the roots of the crisis by decentering the hegemonic position of Western science as the sole possible and legitimate form of knowledge. Decolonial studies help us understand that power dynamics emerge beyond mere cognitive forms of discrimination associated with class, race, and gender within a Westernized and globalized world.

As Rancière points out, power dynamics are not limited to inequalities manifested within a single possible world—the Western modern one—and even less so should solutions be proposed within its confines if they are to do justice to the existence of plural knowledge and worlds.

As Rancière points out, power dynamics are not limited to inequalities manifested within a single possible world—the Western modern one—and even less so should solutions be proposed within its confines if they are to do justice to the existence of plural knowledge and worlds.

At the cognitive level, knowledge systems are produced from worlds beyond the one crafted by Western science. Therefore, cognitive power dynamics operate between knowledge systems produced from different worlds—primarily between Western modern science and knowledge derived from other worlds—ultimately rendering the existence of diverse knowledge systems and, thus, diverse identities, impossible.

From the perspective of a dialogue of knowledge, I propose a decolonial critical review of how the Western-modern cognitive system (even in its most reformist variants) produces knowledge. It does so, based on dichotomies that universalize the fragmented and hierarchical relationship between humans and nature (subjects-objects), thereby violating identities rooted in lifeways from relational worlds in which nature is inhabited—not occupied, as in the Western-modern view.

This demonstrates why a just socio-ecological transition, like any root-level solution for more-than-human and human beings, must be built upon the foundations of epistemic justice.

I use the terms “modern” and “modernity” interchangeably to refer to lifeways derived from the Eurocentric cognitive system, which generates hierarchical-dualist relationships between society and nature; subjects and objects (subjects as observers and objects as static, inert entities); and rationality and bodily sensoriality.

What is the Dialogue of Knowledge?

In recent decades, the dialogue of knowledge (DK) or Diálogo de saberes, an academic and social concept arising from peasant and territorial struggles, has gained strength as a political proposal of resistance. DK challenges the hegemony of science as the sole source of knowledge, questioning its role in imposing ways of being, doing, and knowing that exclude other perspectives and understandings. This concept acknowledges that there is knowledge that goes beyond the limits of the modern Euro-centric and logocentric (scientific) vision, which claims to be the only possible and universal worldview in a globalized world.

On the one hand, DK promotes epistemic justice—an effort to value knowledge and practices excluded by the modernity/coloniality dynamic (as two sides of the same coin). On the other hand, it serves as a space for encountering what is radically different—a bridge that unites without erasing differences and the richness of knowledge systems diversity.

As a form of resistance and critique of the coloniality of Eurocentric knowledge, DK seeks to develop what Mignolo and Walsh call ‘epistemic disobedience.’ This disobedience enables questioning modern thought’s dualistic and Cartesian hierarchies, such as the divisions between subject and object, culture and nature, or logic and emotions. These hierarchies are, arguably, a fundamental cause of the current socio-environmental crisis. This is not only due to unsustainable economic, energy, food, and water models but also to a crisis of meaning and significance—ultimately, a crisis of European civilization, imposed over 500 years of constant invasion.

As a counter-hegemonic response, DK is inspired by the Zapatista vision of a World where many worlds fit—a space where deeply diverse knowledge coexists. These diverse forms of situated knowledge emerge and develop in specific and living territories, challenging even the most progressive positions that seek to decentralize knowledge production within the framework of modern thought. Instead of recognizing legitimacy of other knowledge systems, the modern world has given the right to produce knowledge but within its dualistic epistemic confinements. Thus, the last century has seen the promotion of discourses and practices that appear to democratize power over who can produce knowledge.

These approaches attempt to overcome the limitations of compartmentalized-dualist-heteropatriarchal modernity. Nevertheless, they have so far mostly focused on reformist narratives that do not escape the Eurocentric colonial matrix. Some of the examples of these narratives can be seen in current modes of sustainable development, endogenous development, or the central role of women and their agency in development.

Source: La Via Campesina (https://viacampesina.org/es/colombia-jornada-de-vivencias-10-anos-compartiendo-la-palarba-junto-al-pueblo-organizado1/)

Without a profound revision of and epistemic aspects, these approaches attempt to correct the decontextualized and ethnocentric knowledge of European modernity, where only experts and scientists from the Global North have been seen as ‘rational’ and authorized to define and solve the problems of the Global South.

In the context of climate change adaptation initiatives, for example, biological markers based on the ancestral knowledge of Indigenous peoples in South Asia and Mesoamerica continue to guide communities in their agricultural decision-making. In Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, and southern Mexico, the reduced vocal activity of bird species, such as the Cenzontle, is associated with energy conservation in response to shifts in environmental pressure—changes these birds are able to perceive through a more acute sensory scale than humans. Despite a broad repertoire of ancestral climate knowledge, many adaptation projects based on Western science overlook these epistemologies, even when Western science presents itself as participatory and horizontal in approach. This leads to the exportation of knowledge that is disconnected from the evolving socio-ecological relations in the territories concerned, and to the need to contextualize externally developed adaptation models.

A dialogue of knowledge would instead operate under a principle of complementarity, where no system of knowledge is considered superior to another. In the context of indigenous epistemologies, solutions would emerge from the systematization of local ancestral climate bioindicators. External knowledge, including Western modern climate science, could contribute to local systems through meteorological stations´ data, predictive models, etc. This perspective decenters Eurocentric science´s political power by challenging it as the sole legitimate form of knowledge. This becomes particularly relevant when, on a pragmatic level, evidence shows that meteorological models based on Western science are unable to predict weather patterns at the micro-regional geographic scale.

From the Modern Episteme to the DK’s Civilizational Transition Proposal

A characteristic of modern thought is that it designs the World based on hierarchical dualist divisions. One of the hierarchies of primary interest to DK is that of subjects-objects, through which the World is made comprehensible via mental representations (or models) of an external reality (which is static, meaning a reality that does not pass through bodies or feelings). This aligns with the Cartesian principle of first thinking and then existing, which is characteristic of educational systems cognitively colonized by Eurocentric scientific knowledge.

Another modern hierarchy that DK seeks to deconstruct is the separation between culture and nature. As cultures escape the “limitations” imposed by nature to dominate, control, and inscribe their history onto it as if it were a blank and lifeless slate (a tabula rasa), they progress, develop, and evolve. For the modern world, learning to adapt to the conditions of nature –i.e., living in relationship with nature– is considered underdeveloped, backward, “traditional”.

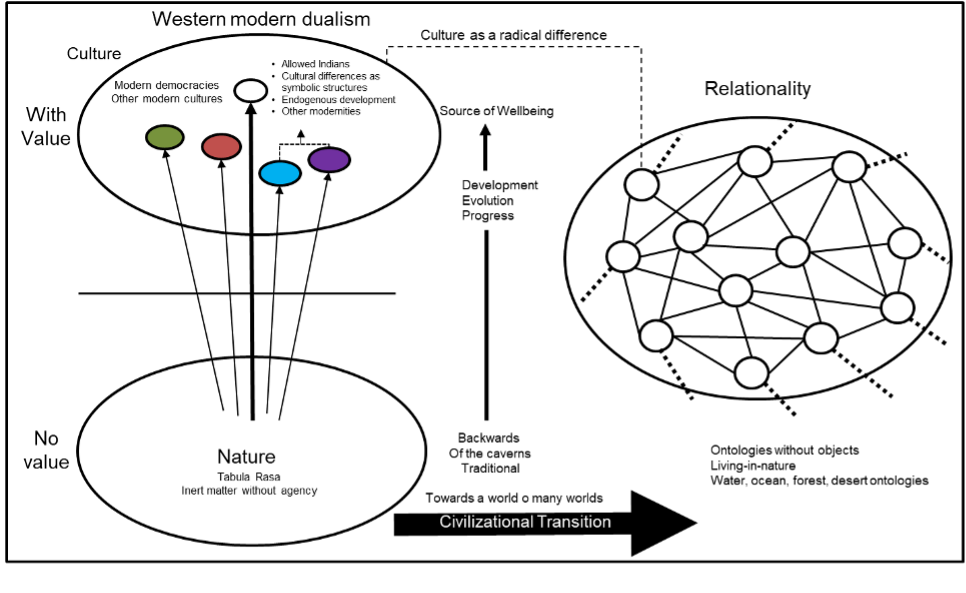

While the modern way of life acknowledges cultural diversity, it homogenizes cultures, erasing the radical identity differences that, for instance, challenge the culture-nature hierarchical division. As can be seen in Fig. 1., within the sphere of Culture (with uppercase) other cultures (lowercase) are included, integrated by the modern way of life. From the perspective of cultural differences as symbolic structures in anthropology, all cultures worldwide have undergone hybridization processes, meaning that, in one way or another, all cultures have already modernized.

Figure 1. Euro-modern dualist episteme and relational ontologies. Source: Own elaboration based on Blaser and . The left side of the figure represents the modern episteme, based on the hierarchical division between nature and Culture (Capitalized). Modernity accepts other cultures (lowercases), producing them, according to Rivera Cusicanqui, as “allowed Indians”—recognizing cultural differences as long as they don’t oppose modernity´s development. Time is perceived as linear and evolutionary, reinforcing the idea of progress, evolution and growth, while nature is objectified as inert matter. In contrast, relational ontologies (right side) produce the world through relations between human and more-than-human beings with life and agency. When such a worldview rejects development projects that harm living beings like rivers or mountains, modernity deems these positions irrational, creating the “forbidden Indian” through its reasonable politics.

Figure 1. Euro-modern dualist episteme and relational ontologies. Source: Own elaboration based on Blaser and . The left side of the figure represents the modern episteme, based on the hierarchical division between nature and Culture (Capitalized). Modernity accepts other cultures (lowercases), producing them, according to Rivera Cusicanqui, as “allowed Indians”—recognizing cultural differences as long as they don’t oppose modernity´s development. Time is perceived as linear and evolutionary, reinforcing the idea of progress, evolution and growth, while nature is objectified as inert matter. In contrast, relational ontologies (right side) produce the world through relations between human and more-than-human beings with life and agency. When such a worldview rejects development projects that harm living beings like rivers or mountains, modernity deems these positions irrational, creating the “forbidden Indian” through its reasonable politics.

Epistemologically, as Enrique Leff states, this implies that all cultures share a ‘background knowledge‘ structured by modern thought paradigms that govern the formulation of rational statements. Any way of living or statement that does not fit within structure of this background knowledge is classified as an ‘absence’ and labeled with categories such as beliefs, myths, non-scientific, or irrational knowledge.

For example, environmental impact assessments (EIAs) often fail to understand the cultural dimensions of environmental conflicts. The Euro modern knowledge system grants itself the right to be the legitimate language (of mental representations) in decision-making processes to endorse projects such as extractive mining, intensive agriculture, and other high socio-environmental impact activities. Such decision-making processes often invite members of communities to present arguments for or against projects exclusively based on “scientific evidence” that must be stated through an EIA. Therefore, it is essential to question discourses of inclusion and integration, as multinationals and government agencies often interpret inclusion as merely translating an environmental study (written in modern language) into an Indigenous language. This reflects an underlying attempt to transfer the modern way of living to other languages coupled to worlds outside the modern episteme, aiming to make modernity work and eliminate radical cultural differences.

In opposition to these dynamics, amidst the negative socioenvironmental impacts caused by the San Rafael Mining company (illegally established) in Xinca’s territory, Xinca’s people (Maya’s people from Iximulew/Guatemala) decided not to continue conversations with the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources and the multinational to express their complaints based on allegedly impartial scientific evidence. In response, they developed the Xinca’s parliament and, under the International Labor Organization’s Convention 169, claimed cognitive sovereignty and autonomy in their territory, communicating that decisions concerning their territory would be made within the framework of the parliament’s proposed perspectives and evidence.

Source: https://aprende.guatemala.com/cultura-guatemalteca/etnias/historia-de-la-comunidad-xinka-en-guatemala/

Beyond the modern episteme, to understand (non-dualistic) relational ways of being,and producing knowledge, we can use Tim Ingold’s spiderweb metaphor. In his metaphor, humans and more-than-human beings (animals, mountains, rivers, lakes, etc.) are living designers with an agency that weave the web—a fabric originating from their bodies. This notion of the spiderweb is similar to what many Indigenous peoples of Abya Yala call the ‘fabric of life’ when referring to their relational worlds-territories. In this framework, human beings and more-than-human beings do not exist in isolation but are always inter-existing with others. When, for example, a modern project causes even a small environmental impact—which could escalate to an ecocide—the consequences can be genocidal, as it affects a being that is part of the web. This implies that the territory’s interdependent identity and the beings that emerge from it are at risk.

For example, as Gálvez-Campos observes, in the territory of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation (located within what is known as British Columbia, Canada), much of the Nation opposes extractivist projects that have gone so far as to label the territory an “energy corridor.” The construction of a distribution network for fracked gas has already begun, causing the migration of moose, wolves, bears, and goats, and endangering the salmon ecosystem. This has escalated to the disruption of the Wet’suwet’en hunting and fishing seasons. However, the multinational company (Coastal GasLink) responsible for these impacts, through its environmental impact study—endorsed by the Environmental Assessment Office of the Government of British Columbia—proposed, as one of its mitigation measures once the construction phase finishes, to compensate with landscape restoration, and throughout the construction process, claims that water quality parameters will remain within national regulatory thresholds.

As Gálvez-Campos points out, Western extractivist projects enter relational territories through their modern dualisms, which split and hierarchize the human-nature relationship, situating nature as an object to be controlled to inscribe their history upon it. Through the discursive assignment of a name (“energy corridor“), modernity, in Escobar’s words, focuses on the ontological occupation of Wet’suwet’en territory. That is, it alters the relationships and ways of life that exist outside of the modern episteme to incorporate them as mere symbolic structures within it (see Fig. 1). However, for the Wet’suwet’en, hunting and fishing are more than trades—they are ways of life that shape their identity, give identity to the territory, and define human–more-than-human relationships. Being Wet’suwet’en is inherently tied to being salmon fishers, to being moose hunters.

At best, assuming that Coastal GasLink’s socio-environmental impact mitigation measures are effective and the landscape is restored after the eight-year construction phase, as Gálvez-Campos notes, the company would still interrupt the Wet’suwet’en ways of life during that time. In any case, these are colonial mitigation proposals.

In addition, in the words of Sleydo´ (Wet’suwet’en spokesperson), “we come here to the river so that our daughter, Winny, knows the taste and smell of the Wedzin Kwa River.” According to Gálvez-Campos, this highlights the importance of sensory cognitive body-territory processes in relational territories. To affect the territory is to affect the identities that emerge from it—hence the inherent connection between ecocide and genocide in relational territories such as that of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation. Drilling into the Wedzin Kwa River also pierces the bodies and identities of the Wet’suwet’en people.

Overcoming the modern way of life with the Thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth

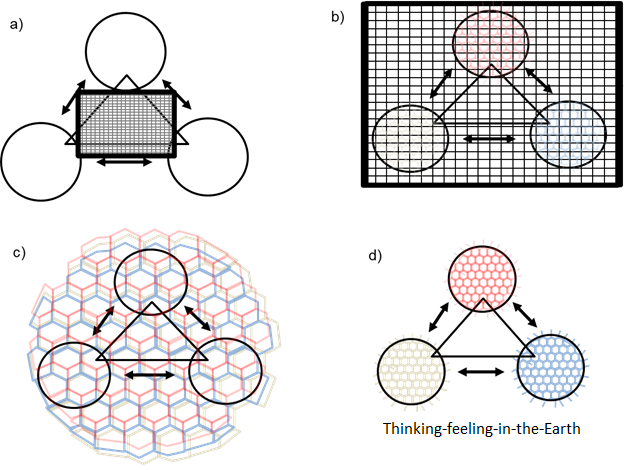

DK can be understood as critical political position against the modern-colonial episteme and a transition toward a civilization guided by thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth. There are various ways of cognitively relating with multiple territories in the world (see Figure 2). Modern Eurocentric knowledge over the past centuries has claimed —through oppressive colonial dynamics— the exclusive right to produce ways of understanding around the earth (Fig. 2a, 2b). Through “instrumentalist rationality,” (Fig 2a) the empty circles symbolize how Eurocentric science approaches communities and territories as lacking the ability to produce their knowledge. From this perspective, only institutions such as uncritical academia, the State, and international cooperation agencies—co-opted by such scientific knowledge approaches—can issue valid and legitimate statements about reality. Other knowledge systems are considered outdated, mere beliefs, and untrue.

Figure 2. a) Instrumentalist rationality, b) Decentralized instrumentalist rationality, c) Communicative rationality, d) Environmental rationalities (dialogue of knowledge / Thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth). Note: The spheres symbolize the territories, while the triangle in the center alludes to the cognitive connection achieved through dialogue.

Figure 2. a) Instrumentalist rationality, b) Decentralized instrumentalist rationality, c) Communicative rationality, d) Environmental rationalities (dialogue of knowledge / Thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth). Note: The spheres symbolize the territories, while the triangle in the center alludes to the cognitive connection achieved through dialogue.

In “decentralized instrumentalist rationality” (Fig 2b), the Eurocentric grid expands, seemingly recognizing some diversity of knowledge production systems (represented by the colored circles in the background). However, this diversity remains subordinated to Eurocentric scientific knowledge. The grid acts as a cognitive filter that only allows aspects compatible with the dominant scientific method. It is as if this system extends an invitation for the inclusion and integration of other knowledge systems—but strictly on its terms. This raises crucial questions: Who integrates whom? Who has the power to include? What remains is not a genuine dialogue of knowledge but rather a monologue. Anything that does not fit within the black-and-white grid of dominant background knowledge is excluded, effectively denying its right to exist.

On the other hand, a “communicative rationality” (Fig 2c), knowledge production systems are integrated with equal cognitive rights, forming a genuinely diverse framework. In this model, dialogue for the (co)construction of knowledge occurs horizontally, recognizing the validity of all knowledge systems beyond modern scientific thought in interpreting and shaping reality. No system holds supremacy over another. Eurocentric science, then, is positioned as just one system among many, on equal footing in terms of legitimacy.

However, political ecologists like Enrique Leff warn that despite this apparent horizontality, the ultimate purpose of knowledge production within the framework of communicative rationality is the creation of universals exported to territories where such knowledge was not produced. Then, a need emerges to contextualize knowledge and to adapt cognitive models to foreign realities. This leads to the development of mental models that perpetuate one of the pillars of modern Eurocentric thought: the exclusion of emotions and the body—essential elements in producing situated knowledge. This omission could limit the full recognition of epistemic diversity and perpetuate certain reductive logic despite the intention of promoting cognitive equality.

In line with Enrique Leff’s critique, and other grassroots territorial movements propose “thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth.” From this perspective, knowledge is generated from and for specific living territories, recognizing its socio-ecological and cultural grounding. For this reason, situated knowledge cannot be exported to other territories without losing relevance. Outside the space where it originates, foreign knowledge systems —including Euro-modern science— should assume a role of possible complementarity but never dominance.

In line with Enrique Leff’s critique, La Vía Campesina and other grassroots territorial movements propose “thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth.” From this perspective, knowledge is generated from and for specific living territories, recognizing its socio-ecological and cultural grounding. For this reason, situated knowledge cannot be exported to other territories without losing relevance. Outside the space where it originates, foreign knowledge systems —including Euro-modern science— should assume a role of possible complementarity but never dominance.

The thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth (Fig 2d) fosters a genuine dialogue of plural knowledge systems in which diverse ways of understanding and constructing the world coexist on equal terms. This approach profoundly links knowledge production with the defense of territories, emphasizing that without territory, there is no cognitive autonomy or sovereignty. Furthermore, the thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth opposes cognitive colonization and, crucially, the invasion of life systems based on knowledge produced in foreign contexts.

Following Segato’s critique, thinking-feeling ways of being are incorporated into the Euro modern project only under the condition of defeated cognitive and sentient beings, thereby perpetuating their subordination. This prevents the right to existence of anything that does not pass through the filter imposed by the politics of Eurocentric-scientific colonial rationality. This filter continues to dictate the being and doing of uncritical State institutions, academy, and non-governmental agencies, thereby reinforcing the exclusion of ways of thinking-feeling-in-the-Earth.

Overall, this essay aims to point toward a socioecological transition in which epistemic justice takes center stage, making possible the existence of knowledge systems derived from relational worlds that challenge the hegemony held by Eurocentric scientific knowledge. The epistemologies in line with thinking-feeling-with-the-Earth —which involve an inherent body-territory relationship— such as those of the Wet’suwet’en and the ancestral climate epistemologies of Indigenous peoples from South Asia and Mesoamerica, offer a path toward establishing a dialogue of knowledges based on the principle of complementarity. This principle holds that no knowledge system is more legitimate than another and that knowledge must be produced from and for a specific living territory. By recognizing the principle of complementarity, there is hope that Western modern science may relinquish its principles of homogenization, universalization, objectification of nature, and cognitive colonial imposition. In doing so, Western modern science could contribute to the cognitive enrichment of other systems through a genuine dialogue of knowledges.

—

Note: The content of this essay was presented at the III International Colloquium on Environment and Sustainability, coordinated by the Colegio de Posgraduados of Tlaxcala, Mexico.

—-

Byron Gálvez-Campos is a researcher at the Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Naturales y Tecnología (Iarna), Universidad Rafael Landívar. His research-action areas include environmental justice, energy democracy and sovereignty, dialogue of knowledge, and ontological conflicts.