by Songze Wu

As electric vehicles are hailed as the future of green mobility, this article asks: are they really a solution—or just a new front for capitalist exploitation? Drawing from eco-Marxism and degrowth, it unpacks the hidden costs behind the EV boom and invites readers to rethink what a truly sustainable future could look like.

On October 28th, 2024, Volkswagen announced plans to close at least three of its ten manufacturing plants in Germany. It was viewed as a response to dwindling demand in Chinese and European markets, ending electric vehicle (EV) incentive schemes and fierce competition from China. This decision and later the agreement with the German workers union, came with significant layoffs, at least 35,000 jobs by 2030.

As of 2024, 60 countries and territories have committed to phasing out combustion engine vehicles to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including the EU’s 27 member states. We find ourselves in a complex landscape of global carbon-free transitions aimed at combating climate change, alongside an intense “green” mobility race. However, this transition to electric vehicles is not without its environmental costs.

The Environmental Cost of EV Production

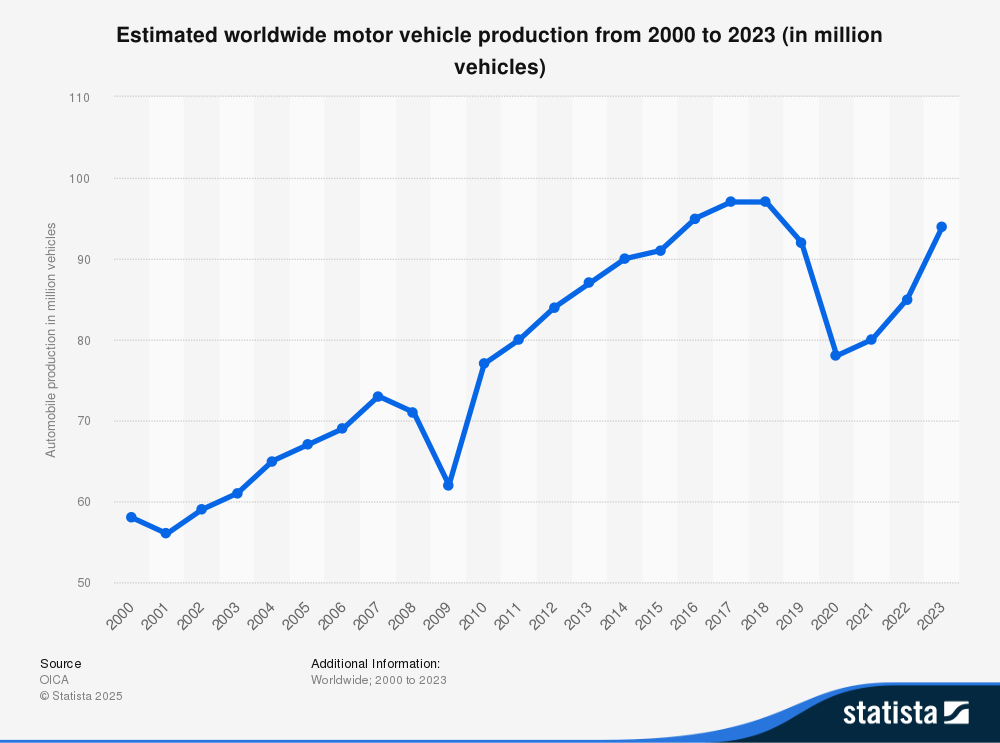

While global vehicle production has rebounded to its pre-COVID peak, global lithium production—a crucial component in EV manufacturing—more than doubled in 2023 compared to 2018. Although EVs are often marketed as a greener alternative, they actually emit more carbon dioxide during production. This excess is only offset after several years of use: about four years in the UK, 5.1 years in Germany, and 9.6 years in China.

Moreover, producing just one tonne of lithium requires approximately 1.9 million tonnes of water. In Salar de Atacama, Chile—home to over 58% of the world’s lithium reserves—lithium mining is severely impacting local communities, consuming 65% of the region’s water, forcing farmers to seek alternative. It was reported that lithium extraction in the region resulted in a sinking salt flat at a rate of 1 to 2 centimeters per year.

At the same time, more effective recycling processes of lithium-ion battery were called upon but have not yet reach full maturity due to its complexity. Despite showing significantly lower carbon footprint than extracting virgin material, recycling lithium usually requires a significant amount of energy input. Based on the source of energy and recycling technique, differences in greenhouse gas emissions could be as high as five times.

However, back at the point of purchase, life cycle assessment as well as embedded environmental and social impact of EVs can be easily overlooked by ordinary consumers, potentially enforcing their unsituated pollution.

Estimated Worldwide Motor Vehicle Production from 2000 to 2023 (Source: Statista)

Lithium Production from 2000 to 2023 (Source: One World in Data)

Potential Alternatives Through the Lens of Eco-Marxism – Closing the Metabolic Rift

Karl Marx introduced the concept of “social metabolism“, and defined that in Capital, “man, through his own actions, mediates, regulates and controls the metabolism between himself and nature”. This was further developed through the term “metabolic rift”, “irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism, a metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself”.

Marx discussed how human could be the agent of change with nature in agriculture. The same can be applied in the process of EVs transformation where land use and human interaction essentially strengthening the metabolic rift. EVs as commodities are developed in factories through collaborative global actions such as mining, transporting, processing, assembling, delivering. As Marx critiqued, “the labour-and-production process, necessarily drew its energy and resources from the larger universal metabolism of nature”.

From EVs’ external appearance, it is difficult to perceive their material and geographical nature origin as well as their disruptive socio-environmental impact. Human consumption of lithium mineral has little or no possibility of returning to its mine and serve its original purpose, where water required for its production might be presented as pollution further threating already low groundwater level in some communities experiencing severe water scarcity like Salar de Atacama.

Furthermore, as Leandro Vergara-Camus suggested, the fundamental cause of the socio-ecological disruption identified by Marx, lies in the inherent capitalist nature of accumulation rather than growth. Growth, in Vergara-Camus’ view, could be made sustainable under full democracy with the abolition of capitalist accumulation and competition. However, the continuous production and consumption of EVs, driven by profit accumulation, would not resolve the rift. If we truly consider metabolism important, we must take a serious step forward. More will be discussed later.

In addition, mining, as a crucial economic practice as we know, boosted by EV transition, continues to impose significant threats if it is not managed properly. These impacts could include habitat destruction, deforestation, workers’ safety, child labour, and toxic-waste contamination. Yet, due to the lack of transparency and the vast existence of illegal or undocumented mines, it has been difficult for researchers to fully understand the scale of impacts from mining activities.

These being said, given the current state of EV development, minimizing lithium production is crucial to addressing this problem. Public awareness of the potential environmental impact of EVs could be enhanced by NGOs and even car manufacturers to fully inform their customers. Recycling facilities and the reuse of EV-related materials could further reduce this damage. Efforts should be made to replenish depleted water reservoirs and purify any water pollution to restore impacted ecosystems.

Fighting against Eco-Imperialism

Eco-Imperialism, with many definitions, could be understood as “imperialistic forms of environmental governance — those that constrain participation in societal decision making, or that cause social and even ecological harm under the guise of environmental protection” as Hugh Dyer described.

Developed from Marxian frameworks, the issue of lithium production, as well as productions of nickel and other essential minerals for EV manufacture, highlight an “imbalanced” imperialistic power dynamic. The Global North continues to exploit the Global South in the name of “net-zero,” “climate,” and “green” initiatives.

There are primarily three methods of lithium extraction: hard rock mining in Australia, sedimentary rock mining in North America, and evaporation of brines in South America. The latter method involves open-air evaporation of lithium-containing brines for several years, draining scarce water resources, shattering local ecosystems, and damaging Indigenous communities.

If we look closely, it is easy to map out a local power structure that perpetuates ecological exploitation in the Salar de Atacama region: local communities and NGOs express concerns about ecological impacts, while mining companies, supported by scientific research, reject these claims.

Government bodies often take a pliant stance, prioritizing economic interests over environmental compliance. This leads to mining companies exerting decisive control over local ecosystems, driven by global market demand and capitalist interests.

John Bellamy Foster’s of Marx’s view provides a reflective point: “Capital as a system was intrinsically geared to the maximum possible accumulation and throughput of matter and energy, regardless of human needs or natural limits.”

In the case of mineral production for EVs, large multinational companies continue to act as primary agents in the process of such eco-imperialism while maximizing profit. This nature of capital exploitation could be mediated through eco-socialist actions that account for community and ecological impacts, such as a North-South redistribution scheme for an EV-related environmental fund, collecting from vehicle manufacturers or consumers in the North and directing funds to conservation organizations and Indigenous communities in the ecologically impacted South.

A Flamingo Drinking Water in the Atacama Desert Salt Flat (Source: Vitor Ávila)

Taking Labour and Nature Not for Granted

Marxists argue that all commodities contain both use value, derived from natural-material conditions, and exchange value, determined by human labour-time valuations. Thereby, nature and labour constitute the dual sources of all wealth. Since the material cost of nature is usually excluded, by only accounting the cost of labour or human-related services, capitalism excludes environmental and social reproductive costs from production. Here, labour is considered also “free”, being excluded from means of subsistence and having no other commodity for sale.

Nancy Fraser identifies the core features of capitalism in three dimensions:

- Ongoing primitive accumulation – the continuous extraction of values from racialised and Indigenous populations.

- Expropriation of social reproduction – the undervaluation of unpaid or low-paid reproductive labour that produce and sustain human beings and social bonds, including childcare, elder care, and emotional labour.

- Nature as “free” resource – the perception of nature as having no inherent cost, whether in resource extraction for production or in absorbing waste.

In the case of EV production, the fundamental labour-nature-production relationship does not change. Lithium is still regarded as a “free” resource from nature. Workers may be laid off in ways that conflict with manufacturers’ financial interests. In the name of a new “green” transportation transition, capitalism seeks to maintain its nature order of maximum possible accumulation.

To confront the climate crisis, we must first acknowledge that it is the result of anthropocentric capitalism’s own making. For both companies and states, reflections upon current economic systems for a true sustainable future should not be limited to different motor systems, be it combustion engine, electric, or hydrogen. Furthermore, it is crucial to experiment incorporating the cost of nature into production. This can either through ecological service value or environmental costs and impacts.

For employees, it is important to have the backing of the state for protection of rights from unemployment. However, it can be easily neglected the right of workers in lithium mines where state’s legislations and enforcement might be insufficient, potentially due to a lack of resources, manpower, or information.

Nonetheless, the idea of disfranchising capital from labour should be challenged. Report indicates that employee-owned firms outperformed non-employee-owned companies in job retention, wages, and workplace health and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, customers could be better informed about the potential impact of the embodied environmental costs of EVs at the point of purchase, similar to “fair-trade” labels on products, which could help to gear up market forces toward eliminating more polluted products.

Do We Really Need More EVs? Or Are They Just the New “SUVs”?: A Degrowth Perspective

Developed from Marx’s school of thoughts, Eco-Marxism proposes an alternative to capitalism towards eco-socialism. It fundamentally offers a supplementary socio-economic system where the power of capital is balanced by the role of state via “ecological, social, and economic planning”.

In Marx’s time, it was understood through “producers to regulate the social metabolism with nature in a rational way” as John Foster putted it in 2015. Then, he also proposes a potential scenario to the balanced system as his version of a Great Transition toward a just and sustainable global future. This transition, he argues, becomes possible amid unneglectable material crises. That affects not only the bottom and middle classes but also push some of the ruling class to begin to “abandon their class interests in favor of humanity and the earth”.

The Degrowth Movement places this transition pathway in today’s context. It acknowledges that the global capitalist framework pursues growth at the expense of human and nature, whilst envisioning for a well-being centric, radically shrinking economy.

Degrowth, as an alternative to “green growth”, fundamentally denounces the notion of “growth” and calls for decolonising “public debate from the idiom of economism”. Furthermore, it envisions a society that consumes fewer natural resources and functions more toward communing, municipalism and the like.

Using a narrative of “SUVs” to refer to socially less necessary productions, degrowth scholars approach such production circularly through the following focuses.

- Reducing virgin material use – minimising the extraction of natural resources at the sources.

- Enhancing efficiency – optimising resource use, including energy and labour, to reduce waste.

- Curbing demand and consumption – encouraging a reassessment of which goods and services are truly necessary.

- Promoting repairs and remanufacturing – extending product lifespans and conserving nature materials.

Ultimately, do we really need more EVs serving the same purpose as our old cars? What about improving public transportation and enhancing working conditions and wages for train and bus workers to create a more efficient transportation system?

The primary reason of Volkswagen’s initial sacking of over 10,000 jobs was its lack in competition with Chinese EV manufactures. As if taken from an old capitalist playbook, it attempts to maintain a traditional labour-nature-production relationship. Just two days after its initial announcement, Volkswagen reported a walloping 42% drop in operating profit in the third quarter of the year.

The story of capitalist judgements impacting labour market and nature environment live on. A degrowth response might involve exploring the possibility of not producing so many EVs, and re-engineering “old” already-manufactured vehicles. It could also be recycling lithium batteries or researching alternative energy sources using currently available materials, such as biodiesel from cooking oil. A conversion business of retro combustion-engine vehicles to more efficient ones could come in style in the consumer market as well the financial one.

Retro Volkswagen Beetle (Source: Giovanni Ribeiro)

Ideology, like technology evolve over time, and schools of thought continue to provide guidance. However, it is difficult to solve today’s problems with yesterday’s mindset—especially when we are expected to consider the future in the name of sustainability.

When Kodak experienced the first hit as Sony introduced digital cameras to the market, disruptively demolishing the need of films, Fujifilm fully embraced the change and swiftly reoriented its assets to further expansion around its competitive advantages through diversifying into medical, printing, electronic imaging and magnetic materials, eventually regaining its footing in alternative markets.

The issue Volkswagen current faces should not only be a wake-up call for the company to preserve its 90-year history and market dominance. It could also serve as a testament to the perspective of degrowth across sectors, especially in times of increasing turbulence.

A Path Forward

Reconciling Eco-Marxism with Degrowth offers a fresh perspective on tackling the climate crisis at the core of supply and demand in a capitalist market, filling the gap in the direction of production while proposing a potentially more sustainable, self-constrained economic model that uses significantly less nature resources. Together with eco-Marxism, it advocates for a healthier socio-environmental relationship, a more equitable Global South and North, and a society driven by well-being. Imagine which reality you would like to live in. This could be one.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Manuel, Lena, and their daughters for hosting us in Germany during the completion of this paper. Certain scenes from Marx’s accounts are still evident today, especially in light of Volkswagen’s announcement, which inspired such further discussion.