by Francesco Torri and Manuel Núñez Fernández

China’s ambition to secure the raw materials for its technological and energy transitions is impacting indigenous territories and ways of life in Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, leaving a trail of pollution and depleted resources that disrupt local ecological and cultural integrity.

The China-South America Lithium Nexus

The “lithium triangle,” spanning Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia, contains 60-70% of the world’s lithium reserves. In recent years, this region has become a focal point of China’s resource acquisition strategy, with Chinese companies investing over $16 billion in South American lithium projects between 2018 and 2024.

According to data from the China Global Investment Tracker, Chinese direct investment in lithium extraction across the region has quadrupled since 2020, making China a major foreign investor in Argentina’s and Chile’s lithium sector. In 2023, China’s Tianqi Lithium and Ganfeng Lithium collectively controlled access to nearly 40% of global lithium production through their South American operations and strategic partnerships.

This dominance aligns with China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), which explicitly identifies lithium as a strategic resource for achieving the country’s energy transition goals, including the production of 21.2 million electric vehicles annually by 2030.

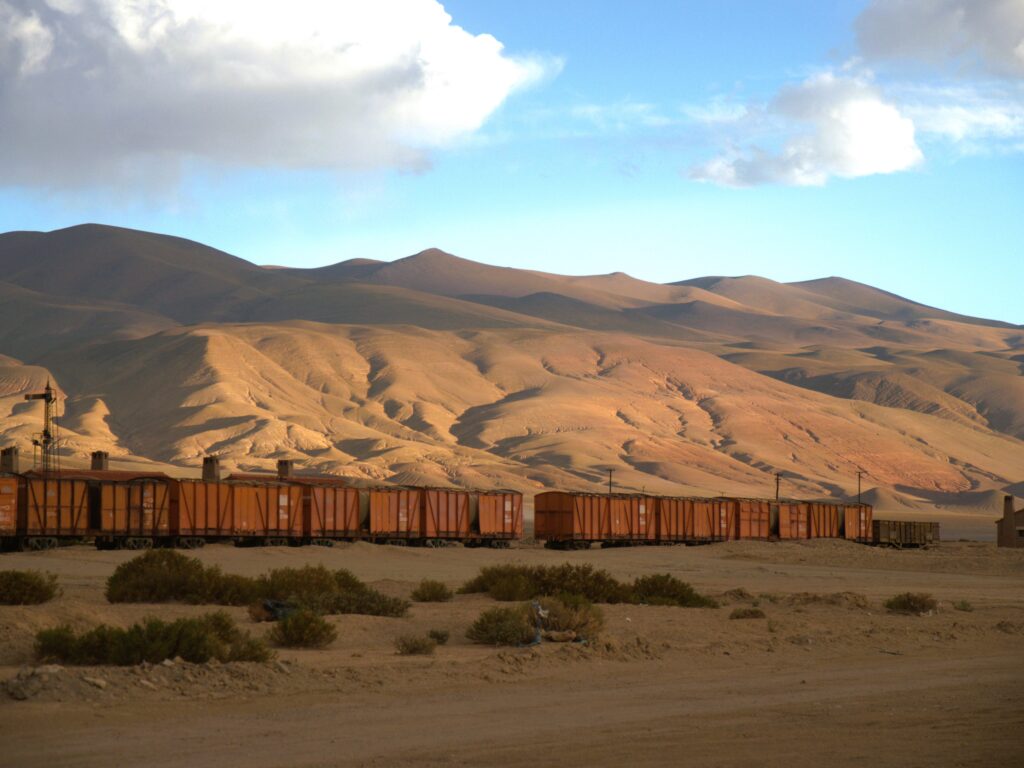

Abandoned commercial train in the village of Pocitos, the puna area of the Salta region, Argentina.

Chinese Investment Models and Local Impact

The arrival of Chinese lithium companies in the North-Western regions of Argentina (NOA) and Chile’s Antofagasta has radically transformed indigenous communities. Driven by China’s ambition to secure the raw materials needed for its technological and energy transitions, these investments have brought environmental, social, and territorial disruptions.

Ganfeng Lithium’s $962 million investment in Argentina’s Pozuelos and Pastos Grandes projects, for example, will have an impact on the ancestral lands of several indigenous communities. Considering that to produce 1 ton of lithium, circa 800 cubic meters of water are necessary, Ganfeng project’s water consumption risk to exacerbate the water scarcity in a region already struggling with access to this vital resource.

Similarly, Tianqi Lithium’s $4.1 billion stake in Chile’s SQM has been linked to declining water tables in the Salar de Atacama, where local communities report wells drying up and agricultural yields plummeting.

“The Chinese companies come with promises of prosperity, but what we see is our water disappearing” explains a Karen Lusa community leader from San Pedro de Atacama, where nearly half the population now lacks reliable water access.

“Their investments are also generating social division, as their strategy is often to inject huge sums of money in areas where people are not used to manage such amounts, leading to corruption and internal conflicts. If you look around there is no real development in the region: infrastructures and basic services are still very poor.”

Olaroz saltflat near the border between Argentina and Chile, where the two biggest active lithium extraction projects are located.

China’s Lithium Supply Chain Strategy

China’s approach to South American lithium is part of a comprehensive supply chain strategy. By 2024, China controlled approximately 60% of global lithium processing capacity, 77% of battery cell manufacturing, and produced 56% of the world’s electric vehicles. This integration has allowed Chinese companies to secure lithium at source and maintain dominance throughout the value chain.

In February 2025, Chinese battery giant CATL signed a landmark agreement with Argentina’s YPF to develop the Salar del Hombre Muerto deposit, investing $1.4 billion to produce 30,000 tons of lithium annually by 2028. This partnership exemplifies China’s state-backed strategy, combining technological expertise with financial resources to secure priority access to critical minerals.

Simultaneously, the completion of Eramine’s first lithium export from Salta to China in early 2025—though a French company—underscores China’s position as the primary destination for South American lithium.

Chinese firms have further cemented their position through partial acquisitions of Western companies operating in the region, such as Zijin Mining’s 2024 purchase of a 25% stake in Rio Tinto’s $2.5 billion Rincon project in Salta. In total, China will invest 3.400 million dollars only for projects in the region of Salta as of 2024.

Water evaporation ponds used as part of the lithium extraction process.

Technological Transfer and Environmental Concerns

China has positioned itself as a provider of lithium extraction technologies to the region, particularly focusing on Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) methods. Companies like Ganfeng Lithium, which owns 122.432Ha of salt flats in the provinces of Salta and Jujuy, promote these technologies as environmentally superior alternatives to traditional evaporation methods, promising reduced water consumption and faster production cycles.

However, a recent study published in Nature rises doubts around these claims, suggesting that DLE technologies may actually consume more water than traditional methods. The study also highlights the high energy requirements of DLE operations, which often rely on fossil fuels in remote locations, undermining the green credentials of lithium battery production.

Zijin Mining’s implementation of DLE at its Tres Quebradas project in Catamarca province consumes an estimated 1.2 MW of power per 1,000 tons of lithium carbonate—power largely generated by diesel generators, raising questions about the carbon footprint of supposedly green technologies.

“It’s important to evaluate case by case whether it actually makes sense to use DLE methods from an environmental perspective, as it may be the case that higher quantities of fossil fuels are burnt than those saved by consumers driving electric vehicles ” explains Ehsan Vahidi, a professor in the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering at the University of Reno, Nevada.

Local indigenous activist from San Pedro de Atacama, Chile.

China’s Policy Framework and Indigenous Response

In February 2023, the Collective on Chinese Financing and Investment, Human Rights, and Environment (CICDHA) has denounced in a report Chinese companies’ lack of social and environmental responsibilities in their extraterritorial mining operations, shedding light on the danger faced by local communities and ecosystems in having such companies operating in their territories.

In this sense, China’s expanding presence could represent a challenge for Kolla indigenous communities of the puna region in terms of territorial conservation and for this reason anti-mining movements have strengthened their defence strategies.

The “Kachi Yupi”, a consultation protocol developed by communities forming part of the association “La Cuenca de Salinas Grandes”, in the province of Jujuy, Argentina, has been adapted to demand higher standards for consultation and environmental protection.

“We don’t want to be the sacrifice zone for wealthier countries. We know they will leave contamination and harm our water resources,” says Elvira Chavez, a young communicator from the indigenous community of Santuario de Tres Pozos.

“For us, this land holds both natural and cultural-spiritual value, while for them, it’s just an economic resource, nothing more. We only ask for respect as the native people of this land.”

Snowy peak of the holy “Nevado Cueva”, on the way to San Antonio de los Cobres, Salta, Argentina.

Environmental and Cultural Costs

The environmental costs of China-backed lithium extraction remain severe. In the Salar del Hombre Muerto, where Chinese-owned Livent operates alongside Ganfeng Lithium, combined water consumption exceeds 10 million litres daily. For every kilogram of lithium extracted, approximately 110 litres of water are consumed, with 90% lost through evaporation or contamination.

These practices threaten not only water security but the broader ecological and cultural foundations of indigenous life. As mining operations expand, sacred sites become inaccessible, traditional migration patterns are disrupted, and the delicate balance of the high-altitude ecosystem is compromised.

“For us, the land is not just resources to extract,” – a local indigenous activist explained during the a water Summit held in El Moreno, Jujuy, at the end of January 2024 – “when Chinese companies talk about efficiency and scale, they’re speaking a language that fundamentally conflicts with our understanding of Pachamama.”

As China pursues its goal of carbon neutrality by 2060—a target that requires vast quantities of lithium for energy storage and transportation—the pressure on South America’s lithium triangle will only intensify. As Miguel from San Antonio de los Cobres warns: “The pace of Chinese investment is overwhelming our capacity to assess its impacts. We need comprehensive, independent studies of cumulative effects before more projects are approved.”

The challenge for indigenous communities, national governments, and international observers will be to ensure that China’s investment practices respect environmental limits and indigenous rights.

The ongoing battle for the protection of indigenous lands in South America’s lithium triangle serves as a stark reminder of the complex interplay between China’s industrial ambitions, global climate goals, and the rights of indigenous peoples.

As China continues to secure its lithium supply chains, the question remains whether this can be achieved without sacrificing the ecological and cultural integrity of one of South America’s most unique regions.

Cover image: Anti-lithium sign written by indigenous communities in Salinas Grandes, Jujuy, Argentina (we want to protect the future of this beautiful nature, no to lithium).

All images are by Francesco Torri.