By Lucia Alexandra Popartan and Camil Ungureanu

In the age of multiple crisis, Vox’s eco-narrative centers on the reassuring promise to restore boundaries, preserve purity, eliminate perceived dangers against Spain’s ‘freedom’, reinstall hierarchies and male authority. This authoritarian narrative, projecting real grievances, grounded in primal emotions such as fear, hatred, and pride, can only be challenged by crafting forceful alternative discourses which rekindle the democratic imagination and are accompanied by structural and material changes.

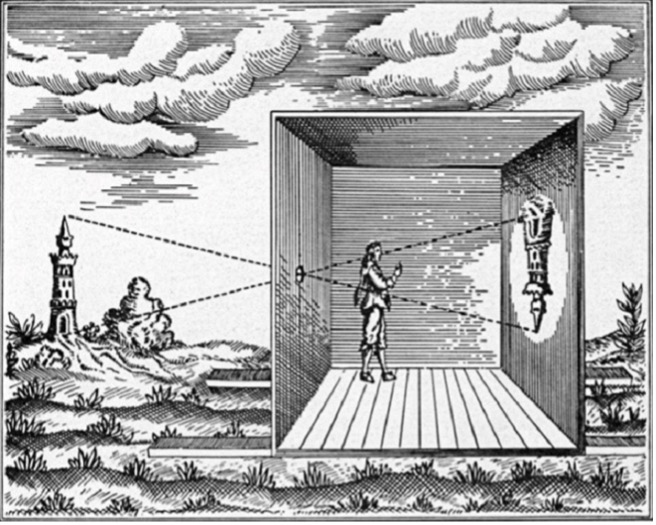

“If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process” (Marx The German Ideology)

1. The populist “camera obscura”

A specter haunts global politics—the specter of national populism. Surges of autocracy, fueled by resentment and anger, have replaced the once-celebrated waves of democratization. By fusing politics, new media, and entertainment, national populism from Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro to Javier Milei and Roberto Duterte has skillfully built the spectacle of an inverted world, recalling Karl Marx’s metaphor of the camera obscura. Through the populist camera obscura, authoritarianism is seen as real democracy and people’s freedom, dismissing feminism as endorsing gender equality, and the systematic use of deception and falsehood as truth and courageous honesty (Trump’s “Truth Social” is paradigmatic for this systematic and trans-contextual rhetoric of inversion).

Illustration of a Camara Obscura. Source: blackcreek.ca

As autocratic forces have gained ground amidst crises of capitalism and representation, European far-right parties have also departed from the sidelines of the environmental debate and developed their ecological agenda. Whereas it is misleading to reduce the varied landscape of far-right parties to eco-fascism, different far-right parties share a rhetoric of inversion whereby they support the “real ecology” against the presumably false ecology of progressives and global elites.

2. The Emergence of Vox and its “Green Turn”

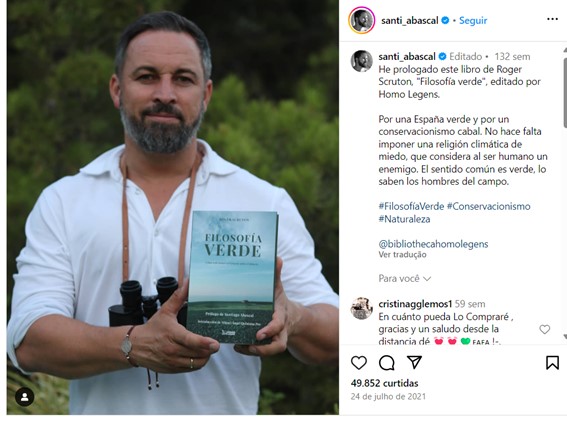

A prime example of an originator of such an inverted world is the far-right party Vox, led by Santiago Abascal, the champion of the “ecología real”. By inverting key societal codes such as real/false, democratic/totalitarian, honest/hypocritical, freedom/oppression, Abascal and Vox portray their “real ecology” as protecting “Spanish nature” against what they frame as the manifold adversaries of Spain championing an “ecological religion” and “dogma.” This “dogma” is an alleged concoction of the Left, European, and global elites imposing a fabricated authoritarian environmental agenda.

Abascal promoting the Spanish translation of Roger Scruton’s book Green Philosophy, for which he wrote the Prologue, in his Instagram account.

Vox, derived from Latin meaning “voice,” is a spin-off of the center-right People’s Party (PP). Capitalizing on the wave of Spanish nationalism, which surged in response to the Catalan separatist movement, Vox made significant strides during the 2018–19 electoral cycle, becoming a key political player in alliance with the PP. Using an alarmist and salvationist discourse, Vox has successfully managed to channel part of the popular discontent with the systemic deficiencies of Spain’s political and economic system. This rhetorical style would later characterize its post-2019 environmental discourse.

Vox’s “green turn” cannot be attributed to a single cause. Factors such as the EU’s heightened emphasis on ecological concerns, the presentation of new financial prospects and incentives related to the European Green Deal, alignment with other far-right EU parties, and the growing concern among a larger number of Spaniards regarding ecological matters all potentially played a role in prompting a discursive “green turn.” Vox’s resulting eco-narrative is, we argue, a fusion of biopolitical imagination and national populism. At one level, Vox eco-narrative operates on a biopolitical logic centered on “life” and “death”—the bios (βίος) as Spain’s political body.

Interestingly, this narrative represents a creative traslation of the struggle between the culture of life and the culture of death, as articulated by the Catholic Church, notably in Pope John Paul’s 1995 Encyclical Evangelium Vitae. Vox extends to ecological issues the biopolitical imagery developed by the Catholic Church regarding euthanasia and abortion and its global “crusade” for the culture of life (Pope John Paul, Evangelium Vitae 1995). Likewise, Vox has centered its ecological discourse around the defense of the España Viva and the culture of life against different mortal threats.

The national-populist tenets are also key to Vox’s eco-narrative, depicting a mythical struggle between the righteous and good People/Nation and the evil Elite/Enemy. For instance, Abascal, speaking at a prominent campaign rally in 2019, urges Spaniards to decide between the Left’s “treason pact” and Vox’s “patriotic perspective,” between “disintegration” and ensuring the “survival of the homeland.” He proclaims that the real choice lays between España Viva (a proxy of “life”), embodied by Vox, and Anti-España (a proxy of “death”, decay, and betrayal), an expression deliberately resurrected from Francoist times. This discourse revolves around the impending downfall or catastrophe for Spain and its natural landscapes, intertwining the concepts of “Nation” and “Nature” within the vision of a historical and proprietorial bond.

Whether in a rally or a parliamentary address, the nation and its natural environment are portrayed as decaying and constantly besieged by both internal and external traitors. In the 1930s, Franco used this term to justify the post-civil war repression, stating, “we, Spaniards, have not fought a simple civil war between brothers; it was a war of Spain against Anti-Spain”. By reviving the Manichean narrative of the “two Spains,” Vox’s authoritarian narrative provocatively instrumentalizes political emotions such as the fear of one’s community’s decline and the belief in the group’s victimhood. Through Vox’s camera obscura, the language of peaceful democratic debate and opposition is morphed into the bellicose idiom friend/enemy (traitor) with sinister Schmittian undertones.

Vox presents a revived version of the “Anti-Spain” championed by a mythical enemy, an amalgam of (sometimes contradictory) actors, ranging from degrowth activists, feminists and Catalan independentists to the United Nations and China. Similarly, diverse stances, from capitalist growth and Agenda 2030 to anti-capitalist degrowth, are all thrown into the sack of a supposed “global environmental consensus”, which is nothing but a “sect,”, “promoting a “totalitarian dogma” or an “ecological religion”. Vox denounces the “elite” (casta), the “bureaucracy,” and “politicians,” championing instead the “common sense” of the “pure” Spanish people. In so doing, Vox targets environmental movements and the Left as new symbols of Anti-Spain in a spectacle of hatred and gleeful spite: from progressives to animal-rights activists and vegans (humorously and derogatorily termed as “lettuce-eaters”), all are portrayed as exploiting environmentalism to manipulate the population and potentially establish an authoritarian-dystopian regime epitomized by the United Nations 2030 Agenda.

3. Rural Spain, Empty Spain, Dry Spain

The narrative depicting a Spain in turmoil, endangered by the ruling elite, is vividly articulated in Vox’s portrayal of rural Spain. While the rural question initially held peripheral significance in Vox’s political agenda, it has steadily evolved into a cornerstone of its environmental narrative. The issues of rural depopulation and severe droughts has provided Vox with an opportune context to advance its catastrophic depiction of Spain. As a result, Vox profusely resorts to topoi such as “Empty Spain,” which is interchangeably used with “silenced Spain,” “abandoned Spain” or “dry Spain.”

To address this “catastrophic” situation, Vox’ environmental policy proposals blend an ecological modernization discourse with traditionalist conservation postures.

Vox’s “Green Spain”: reconciling Industrial Capitalism, Rurality, Family, and the Protection of Nature (Source: Vox’s official Twitter)

In the water sector, Vox takes a technocratic approach, which recalls Franco’s hydraulic imaginary, envisaging grand engineering projects such as river transfers, the construction of reservoirs and dams to supply water to privileged uses like agriculture and hydroelectric companies. In the energy sector, Vox talks of “energy sovereignty”, defending nuclear plants, deregulation to attract foreign investment, but also small photovoltaic electricity generation, to help preserve rural landscapes.

4. “Real ecology” as the latest ruse of capitalism

In advocating its policy proposals, Vox has been keen on co-opting and inverting the terminology of “common good” and “energy poverty” to frame rural and non-rural issues. Vox amalgamates its conservationist statements with a green capitalist narrative, viewing nature predominantly through an anthropocentric lens, either as a national resource or a commercial prospect. When faced with real-life conflicts between environmental conservation and commercial concerns, Vox’s “real ecology” consistently dismisses substantial environmental policies in favor of protecting business interests. Not unlike other far-right forces, Vox’s ecological rhetoric obscures its practical rejection of meaningful climate policies. Vox’s masks such ideological contradictions and inconsistencies with an eco-populist narrative, giving voice and exploiting the Spaniards’ rising sense of disillusionment and socio-political disempowerment, triggered by political-economic and climate change crises.

Abascal as the mythical male figure of the Cid Campeador (Vox’s Official Twitter)

In the age of polycrisis, Vox’s green capitalist discourse centers on the reassuring promise to restore boundaries, preserve purity, and eliminate “ambivalence” and perceived dangers against the freedom of the Spanish nation. The Spanish far-right party further pledges the reinstalment of hierarchies and the resurgence of male authority epitomized by the salvationist figure of Abascal, portrayed as a contemporary Cid.

A powerful authoritarian narrative, projecting real grievances of the dispossessed in capitalist societies into a compensatory inverted world and grounded in primal emotions such as fear, hatred, and pride, can only be challenged by crafting forceful alternative discourses. These alternatives must appeal to both emotions and reason, rekindling the democratic imagination and be accompanied by structural and material changes.

This blog post is based on the findings from a recent study on far-right ecologism conducted by Camil Ungureanu and Popartan Alexandra (2024) titled “The green, green grass of the nation: A new far-right ecology in Spain,” published in Political Geography, Volume 108, 102953. Support for this blog was given by the Centre for Studies on Planetary WellBeing, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Planetary Wellbeing-Segment PLAWB00722 (2022-2024) (Coord: Camil Ungureanu).