by Francesco Torri

The Tariquia reserve in the Bolivian Amazon is once again threatened by hydrocarbon extraction, despite its highly sensitive ecosystem and the threat of pollution to local indigenous and peasant communities. The Bolivian government continues to promote an extractive agenda in the Amazon, despite its allegedly pro-indigenous stance.

The Reserva Natural de Flora y Fauna de Tariquia (Natural Reserve of Flora and Fauna of Tariquia), near Bolivia’s southern border with Argentina, in the Tarija region, is a 250,000-ha area home to more than 600 plant species and 800 animal species, including pumas, jaguars, and jucumari bears. In this green lung, part of the binational ecological corridor Tariquia – Baritù, live about twenty peasant and artisan communities, totaling about 3000 people belonging to four municipalities in the Autonomous Department of Tarija.

The Tariquia reserve seems to exist on another timeline.. The people move around on horseback, carry logs of wood on ox-drawn carts, and grow maize, from which an extraordinary variety of food products are made. In the evening they sit around the fire and drink mate. Electricity has only recently arrived and many still prefer to cook with wood. When the men are harvesting corn, the women prepare fermented cornmeal and tamales, rolls of meat, and potatoes in a cornmeal dough.

Horse expedition to monitor the location of the domo oso X2 oil well (source: Francesco Torri)

This highly biodiverse ecosystem, known as the ‘Bosque del Yungas Tucuman – Boliviano’, has been in the sights of the oil and gas industry since the 1960s, when the first underground explorations in the San Alberto field revealed the presence of hydrocarbons. However, prospective drilling yielded poor results: between 1966 and 1989, only in one of seven wells hydrocarbons were found, but even that was closed due to technical challenges.

In 1989, after almost 25 years of oil exploration, the area was declared a protected nature reserve thanks to the ‘Supreme Decree No. 22277’ issued at the request of local inhabitants and civil society. This stopped the exploration of hydrocarbon resources in the area. However, the environmental damage of unregulated mining operations has never ceased to affect the lives of those who depend on the reserve’s ecosystem to survive.

Some of the locals I interviewed said that, in 2004, the rivers were still full of dead fish, while goats, and sheep were dying young, and no one could drink the river water because it smelled like oil. In those same years, an increase in leukemia cases began to be recorded.

A new chapter for the Tariquia Reserve

In 2014, the Morales government approved a new environmental management plan for the Tariquia reserve. This sudden and unjustified change, which took place without consulting the local communities and without making any authorization documents public, did however rely on the controversial approval of SERNAP (National Service of Protected Areas). The new management plan envisaged a change in the territorial zoning of the reserve to reduce the protected areas and make room for mining activities. Thus, the area available to local breeders and farmers was drastically reduced, and the hitherto intangible ‘core area’ was opened to oil operations.

In 2015, then Bolivian President Evo Morales passed a controversial legislative decree (Decree 2366) that removed the intangibility of twenty-two protected areas in the country, thus opening up the Tariquia reserve once again to oil and gas extraction projects.

Astillero X1 oil well (source: Francesco Torri)

In Bolivia, the only company authorized to engage in the production and marketing of hydrocarbon products is the state-owned YPFB. This is the result of the so-called ‘third nationalization’ of oil in Bolivia, initiated by Evo Morales at the beginning of his first term in 2006. This implies that foreign companies in the sector can only operate through service contracts with the state-owned company, whereby the latter is given the right of ownership over all hydrocarbon production. To date, those who benefited the most from these contracts are the Brazilian giant Petrobras and the Spanish-Argentinean Repsol.

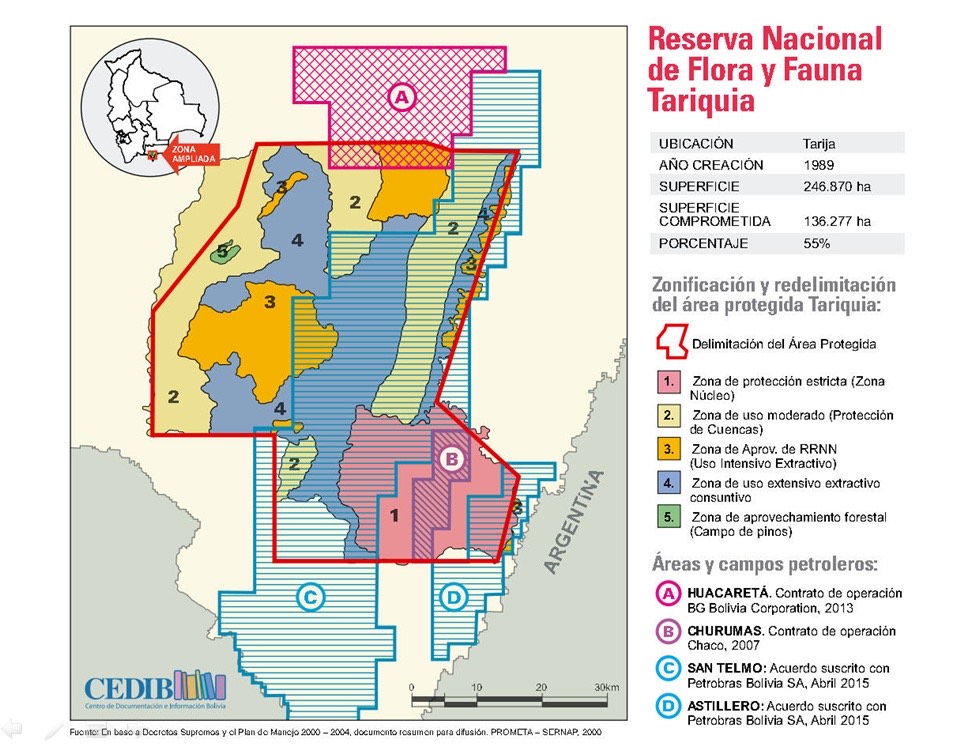

Petrobras itself was awarded in 2018, through a joint venture agreement with YPFB Chaco, a subsidiary of YPFB, 60% of the operation titles and the environmental license for the exploration of five wells in the protected reserve of Tariquia: ‘Astillero X1’ and ‘Churuma X1 and X2’ in the southern area of the reserve and ‘Domo Oso X1 and X2’ in the San Telmo Norte area, north of the reserve. With a total investment of almost USD 200 million and an expected productivity of two trillion cubic meters of gas, the hydrocarbon project covers an area of 136,277 hectares, comprising 55% of the protected reserve.

Considering that this is the outcome of a law approved during the MaS (Movimiento al Socialismo) era, it is apparent the contradiction between Evo Morales’ discourse and the treatment he reserved to many rural and indigenous communities. It’s enough to talk with local minorities of the Tariquia reserve to understand that most of the people here feel betrayed by Evo’s “pro-indigenous” left.

If his government started with a strong purpose to empower indigenous peoples, Evo’s strong ties with the military sector and its interests in the development of coca plantations, made him lose track of his objective. This derailment reached its peak on the 25th of September 2011, when Evo ordered the military repression of an indigenous march walking from Trinidad, in the Bolivian Amazon, to La Paz, claiming the protection of their territory threatened by the mining sector. This episode, known as the Chaparina repression, is the emblem of Evo’s loss of legitimacy: how can a pro- indigenous president order the repression of an indigenous group pacifically fighting for their land?

Heavy machineries at the entrance of the Tariquia Reserve (source: Francesco Torri)

In 2019 the campesino resistance succeeded in blocking the entry of oil tankers

Nelly is a woman in her sixties and her hands are rough from working in the fields. She always carries a sling in her breast pocket to chase away the sparrow hawk that wants to steal her chickens. She has a revolutionary spirit and does not accept injustice, let alone having her land invaded by oil companies. Indeed, it was her, together with her husband Andres, who organized the resistance blockade that in 2019 prevented Petrobras from drilling the Domo Oso X1 and X2 wells in the San Telmo Norte area. The blockade, formed by a hundred peasants motivated to defend their territory, prevented access to the bridge of the Chiquiaca area. For six months they withstood the cold and rain, placing logs and chains on the road, without yielding to the company’s attempts to negotiate. Then they dismantled their tents and marched to Bolivar Square in the center of the city of Tarija, supported by thousands of people. Most locals believe that the fires that swept through Chiquitania in those same days, in the east of the country, were strategically planned by the government to shift media attention away from the protests.

Nelly speaks proudly of the day when YPFB Chaco temporarily desisted from the project. However, today the company is faced with a different scenario: a community that over time has allowed itself to be divided and bought off by job offers and financial compensation.

Something similar happened in the community of ‘El Cajon’, in the south of the reserve, where the locals had already authorized the project in 2019. The few who had tried to oppose it claiming that the local people had not been consulted, suffered aggression and threats.

Don Isidro, for example, was shot eight times. Don Andres has almost been stabbed. Don Marcos was kidnapped for a day. All three cases were linked to community members supporting the enterprise. The instigator, according to the victims, is probably the enterprise.

In this way, the operations in the Astillero X1 well were able to start smoothly on February 2, 2023, without prior consultation with the communities and without the locals being able to know what risks the project implies.

Some of these risks include water, air, and soil contamination due to the use of the landfilling system, in which various toxic wastes from the drilling process are buried in large pits. This leads to groundwater pollution with heavy metals, soil acidification, imbalances in ecosystem equilibrium, reduced photosynthesis capacity of plants, and the release of greenhouse gasses resulting from the decomposition of waste by soil microorganisms.

A map of the territorial zoning of the Reserve and the location of the oil camps (source: Centro de Documentation e Informacion Bolivia)

Tariquia is again under attack

Taking advantage of the campaign to relaunch exploration and exploitation of the country’s hydrocarbon resources following the election of new President Luis Arce Catacora, companies have resumed operations in the Tariquia reserve in 2022. The campaign, justified by the necessity to increase production and resume exports, envisages an investment of $2000 million from 2022 to 2024. As E. Galeano wrote in his masterpiece, ‘In Latin America it is normal: resources are sold off in the name of the absence of resources’.

In the San Telmo Norte area, where 4 years ago protests stopped the companies, the start of the exploration of the Domo Oso X1, X2, and X3 wells has been publicly declared a ‘force majeure’. This means that given the high potential of these wells, and to fulfill President Arce’s promises, the operations are considered to be of the utmost urgency, although two of them are within the protected area, and one is located in a basin with abundant water resources of fundamental importance to local communities.

However, as was the case with the Astillero well, consultation with the peasant communities living in the area did not take place. By law, companies in Bolivia must consult peasant communities in a free, prior, and informed manner whenever they develop activities or projects that have an impact on them. In the Tariquia reserve, this means that communities should be informed in detail about the consequences of the extractive project and based on this knowledge participate in the decision-making process.

What happened was that the companies convened meetings with selected members of the community, in which they simply declared the start of operations and the offer of jobs for a lucky few, all after having already obtained the environmental license, signed the contract with the state and installed themselves in the area.

The community members interviewed had no idea what it was really like to live in an area of hydrocarbon activity.

Not even Nelly and Andres, the activists leading the Tariquia defense movement, knew that the risks of the environmental impact study project were alarming, given the high ecological sensitivity of the area involved.

They did not know that the risk of pollution of the Chiquiaca River and other water resources by chemical spills is considered high in the baseline system proposed by the company; or that according to this same system, the impacts of waste gas combustion (HC, CO, CO2) on air and soil quality will be severe; or that habitat fragmentation due to deforestation will lead to the disappearance of many species of fauna from the area.

In Latin America, it’s a common pattern for extractivist companies to take advantage of poverty and lack of access to information to gain access to protected territories. I saw it in the Ecuadorian Amazon, where oil and gas companies were promising indigenous communities to build schools and hospitals in exchange for access to indigenous territories; I saw it in Brazil, where the Canadian company BeloSun Mining was presenting misleading information about the mining project to local indigenous communities to get their consent.

For all these communities, the only way to survive the pressure of the companies is unity and knowledge. The more people are aware of the consequences of extractivist businesses, the more they can stand together against exploitation, and the harder it will become for companies to develop their projects. As the famous song of Victor Jara says “El pueblo unido jamas serà vencido!” (The people united will never be defeated!).

Francesco Torri is an investigative journalist trained in environmental law, currently reporting on socio-environmental conflicts linked to the misconducts of multinational companies. You can follow him on Instagram @resistance_voices.