By Sahana Subramanian.

Bengaluru is known as the ‘garden city’ of India. A reflection on what this privileged title really represents when we considering the exclusionary nature of the city’s green parks.

I fondly remember meeting my new classmates for the first time at Stadsparken in Lund on a sunny afternoon in August. Besides the nervousness of meeting new people after a year of being in total lockdown due to COVID-19, I had an added layer of reservation as we had planned to meet in a park where I assumed, there would be several new rules and regulations that I had to follow. As I reached the park, the nervousness I had quickly became obsolete. I was pleasantly welcomed by sights of families and groups of friends enjoying the last weeks of summer without hesitations or reservations in freely occupying and claiming space which was rightly theirs. I didn’t think much about this at the time, as I was positively overwhelmed meeting my new friends, but over the course of a year and visits to more parks in Lund and Sweden in general, it dawned on me that this experience of freely accessing commons was unique to me.

Bengaluru, the city I am from, is also known as the ‘garden city’ of India. As of 2022, Bengaluru boasts 1,118 parks in the BBMP (Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike) zone, which is the zone under the urban municipal government agency. There are more parks in the city if one includes those under the jurisdiction of other governing bodies such as the Bengaluru Development Authority, the Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board, or the Karnataka Horticultural Department. Most parks in Bengaluru have concrete paved walking paths and benches to rest on, while some parks also have playgrounds for children and outdoor gym equipment. The plants that are grown in these parks are often of an exotic variety and cater exclusively to the elite imaginaries of a ‘global’ city. A study conducted in Bengaluru shows that 77% of trees in Bengaluru’s parks are not native and belong to introduced species groups. The study also found that newer parks in the city have less species diversity and the preferred species of introduced plants in these parks are smaller and easier to maintain, unlike older parks that have more species diversity and are home to larger canopy trees.

This is indicative of the changing nature of parks and commons in the city. Bengaluru was once home to culturally and historically significant urban commons like wooded groves, known as gunda thopes in the native languages. Gunda thopes provided fruits, food, and fuel wood for people and welcome foragers. The species of plants that were grown in these older commons such as mango, jamun, jackfruit, tamarind, and banyan trees, were native to the region and were selected based on the community’s social and economic needs. Studies of gunda thopes in Bengaluru describe how at the village level, the thopes were cared for and managed collectively by all villagers and the use of the thopes was regulated by the village headman and village accountant. These thopes were accessible to all and the fruits from the trees were collected upon ripening and shared amongst the village residents. However, many of these thopes have now been converted into more urban forms of land use due to increased prices of urban land, illegal land dealings, and other pressures of urbanisation.

This conversion comes alongside a change in the governance and maintenance of the commons from collective management to a hierarchical mode of governance that often does not take into consideration the needs of the local communities before arriving at decisions regarding the plant species that will be introduced in the parks of the city. In their study of guna thopes in Bengaluru, researchers from Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, observed that some had been converted into modern parks, a new use of the wooded commons. These modern parks do not bear fruits or provide fuel wood due to the exotic variety of plants that are grown and the severe policing of park resources that do not allow foraging. This limits people from lower socio-economic groups, who are the most vulnerable to changes due to urbanisation, from accessing additional nutrient supplements and from opportunities to earn an additional income. The ‘criminalisation’ of informal methods of accessing nutrients and additional income through fines, bans, and vigilant policing, create exclusionary citizenship at the expense of the urban poor. This reinforces the idea that the city is designed for the elites.

Parks in Bengaluru have limited opening times. A recent circular issued by the BBMP in 2022 stated that parks would from now on be open eleven hours a day except for three hours in the middle of the day for maintenance work, and will be completely closed at night before re-opening in the morning at 5 a.m. This is after several years of BBMP parks being open for only seven hours a day. These rules restrict the time people can access the parks. Women, like my mother, prefer using the park in the middle of the day after 10 am as their mornings are consumed with domestic activities and care labor due to stipulated gender roles in the households. It is more common to see groups of older men frequent the parks every morning engaging in daily exercise, coffee, and gossip.

Exclusion is also experienced by those who routinely lead lives outside the posh IT offices of Bengaluru, without air conditioning to relieve heat stress, and with no available green spaces to rest or take breaks protected from the heat in the city, especially during the hot summer months. Street vendors, pourakarmikas (sanitation workers, mostly women), and construction workers, for example, cannot enter parks that offer a cool haven against the dusty city heat during the hottest parts of the day as the parks are closed during the afternoons. Children from government schools, who do not have access to greenery in their schools unlike children studying in private institutions, cannot run about freely in these parks during the day as the parks are closed. Therefore, it becomes clear that the intervention of locking up parks for maintenance creates exclusions that are socially differentiated along lines of gender, caste, and class –socio-economic structures then determine who has access to these public parks and for what purpose.

Parks in Bengaluru have a slew of rules that are posted inside the park gates. Some examples of rules include – no walking in anti-clockwise directions, no jogging or running, no taking photos or videos, no playing games, no sitting on the lawns, no eating, and more. These restrictions are colonial and come from the British Raj’s legacy of parks and gardens as spaces for the civilized and as a way of civilizing the people they wanted to dominate. Like other cities in India, Bengaluru was also subject to such features of colonialism as it severed as a military base for the British and as a preferred area for many British settlers. Now, during opening hours, some parks have security guards stationed outside and inside the park gates who routinely surveil and patrol the park, penalizing those who break rules with fines. This creates a hostile environment for park-goers and limits the options of what people can do for recreation in the city. Picnics and hangouts with friends and family, or dates with a loved one in parks are out of the question. People are then forced to choose options for recreation where they must pay several hundreds of rupees such as restaurants, gyms, malls, and movie theatres. This contributes to the neoliberal and capitalist ideal of a megacity or world city where money is the language of leisure, and severely limits access to leisure in open green spaces. Therefore, urban nature and its benefits in terms of good health and recreation, are limited for most people in the city.

A slew of different rules in parks across Bengaluru. Source: Author (2023).

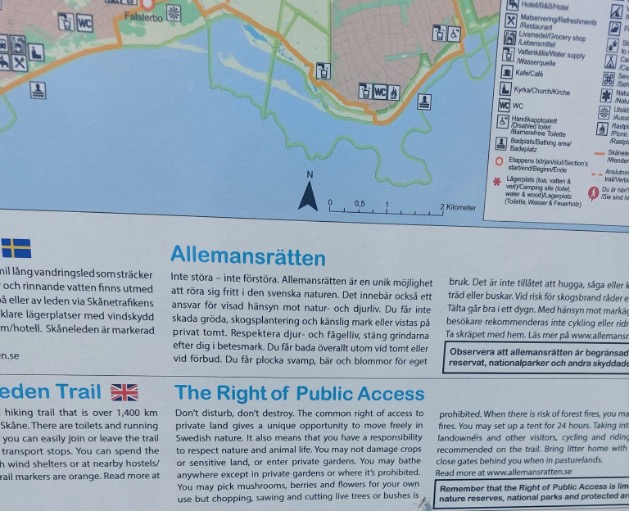

As I cycle past Stadsparken every day, I reflect on the exclusionary nature of parks in Bengaluru, a city very dear to me. Experiencing allemansrätten, that is, the freedom to roam or ‘everyman’s right’, in Sweden has been a constant reminder of how this one year of living abroad has challenged my ideas of what I once considered to be normal for accessing parks. It has encouraged me to envision a transformation of Bengaluru’s parks as inclusive spaces for all and not only reserved for the recreation of elite groups. Through my experience, I now empathize more deeply with the struggles of various citizen groups, such as Citizens for Bengaluru, Heritage Bekku, Environment Support Group, and Maraa, amongst many others, that have been fighting for years to protect what is left of the open green spaces and parks in Bengaluru. Understanding the socio-economic and colonial history of Bengaluru and critically examining urbanisation in the city can expose the challenges of Bengaluru’s parks and can help create inclusive open green spaces for all.

Sign showing Allemansrätten in Sweden. Source: Author (2023).

—-

Sahana Subramanian is a PhD candidate at Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies. Previously, she has worked as an activist using public interest litigations to demand equitable and just access to public spaces in Bengaluru. Sahana advocates for creative collective action for better urban futures.