ENTITLE Blog presents two reflections on the dystopian world of the Handmaid’s tale. In the first, Júlia Hosta Cuy argues that the bleak future depicted in the series and the book should not make us complacent about the current position of women: liberalism is not the alternative to theocracy.

The huge success of Hulu’s 2017 web television series, the ‘Handmaid’s tale’ (receiving widespread critical acclaim and eight Primetime Emmy Awards including Outstanding Drama Series) brought back to attention Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel of the same name. The book and the series are situated in a not so far future, where the theocracy of Gilead has established itself in parts of Eastern USA after a Second American Civil War. A group of fertile women in Gilead, called “Handmaids”, is forced into sexual and childbearing servitude. The chilling parallels with USA in the Trump era did not escape viewers or critics, pronounced in the TV series with a visual aesthetic that made the dystopia eerily contemporary.

Present dystopias

by Júlia Hosta Cuy

It is an environmental disaster, and the dramatic decrease in fertility that ensues, which serves as the excuse to establish the religious authoritarian regime of the Republic of Gilead. Named after a biblical region, Gilead is a hierarchical society where women have no real power, no autonomy, no place in political decisions or intellectual life. Even the women from the upper classes are reduced to just wives.

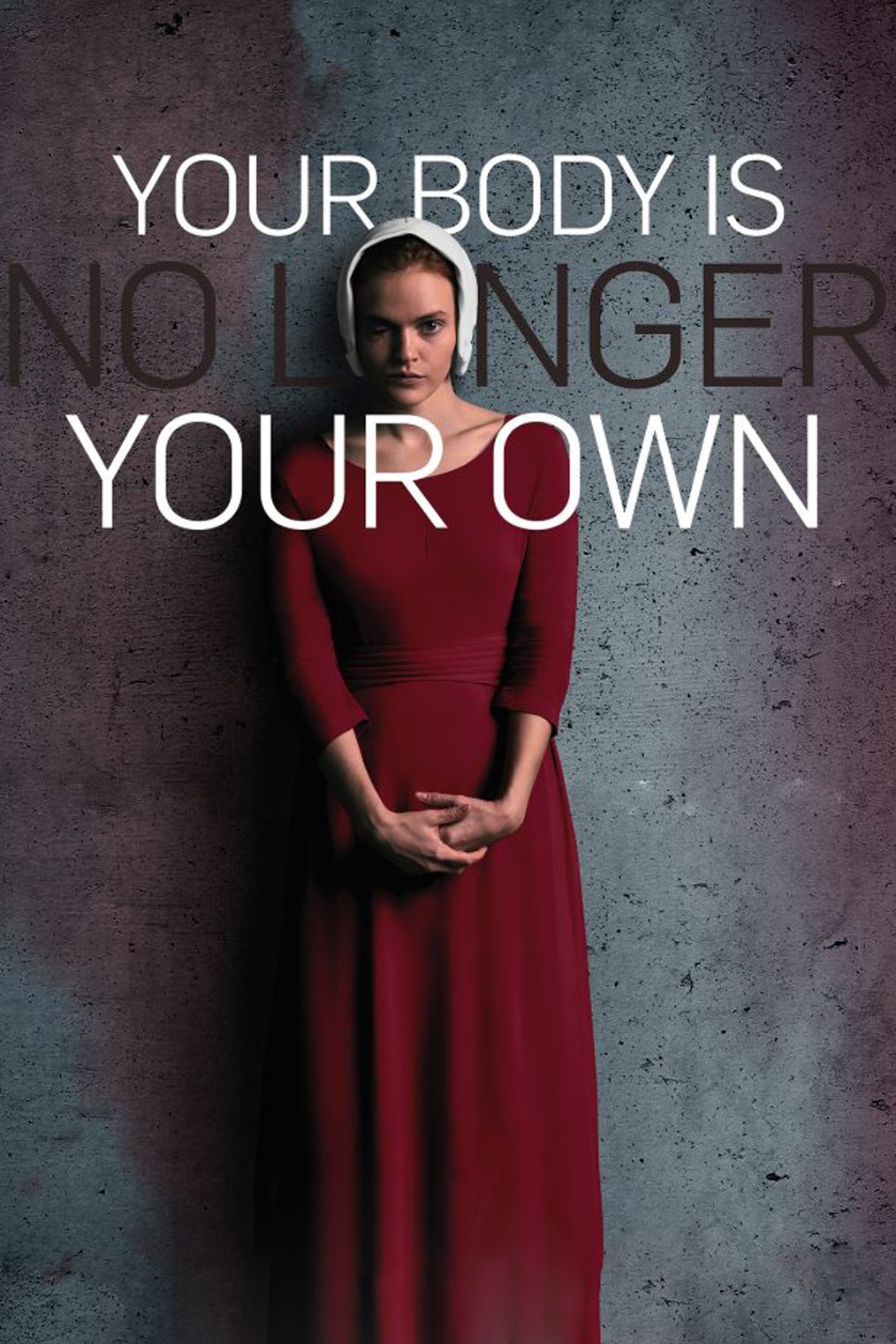

The authorities control and own the body of the few remaining fertile women with just one purpose: procreation for the nation and its upper class. Like June, the protagonist, the red-dressed handmaids are raped in their fertile day of the month by the ‘Commander’ (Fred, hence June’s Gilead name ‘Offred’), in a religious ceremony.

The whole Gilead is in a social and ecological crisis: the population is declining without regeneration. When a Mexican ambassador visits Gilead, we learn that the crisis is not confined to Gilead only – the Mexicans also want handmaids to move their own economy and they are willing to trade them with oranges.

In Gilead, the body of the handmaids is transformed into a baby-making machine, a uterus with legs as Moira – June’s friend – points out. Handmaids are subjugated to the reproduction of the ruling class. This process of commodification of womens’ bodies is not a new story. As Silvia Federici and Nancy Fraser, among others, have pointed out, the exploitation of women’s bodies, through reproductive work and the production of new workers, is a key mechanism, along with nature and colonial exploitation, of capitalist accumulation – primitive and continuous. In Gilead, the exploitation of the women’s bodies is justified, as so often has been the case in history, in the name of the Nation and its stability. Like the 16th century witches, who were deprived of their traditional means and knowledge of contraception and abortion, the handmaids can no longer be sovereigns of their physical bodies. This body-dispossession or body-alienation is, similarly to what happened in the beginning of capitalism, accompanied with the loss of their role as workers or their intellectual active life.

Source: Business Insider

The most moving scene in the book (and the series), according to me, is when Commander Fred, in his personal meetings with June, gives her a women’s magazine he has kept in secret from the period before the theocracy. The commander asks June: “Do you miss this? A list of made up problems. No woman was ever rich enough, young enough, pretty enough, good enough”. To which June responds, “We had our choices then”.

It is this juxtaposition of present day liberalism as the better alternative to a dystopian future that I found most disturbing. The Commander is obviously wrong. But what is real in the freedom women have in our time, so nostalgically cherished by June? Her choice of freedom before Gilead was shaped by the capitalist and patriarchal system in which she lived. In Freire’s words, in Gilead is easier to differentiate between oppressed and oppressors. This separation may be diluted in our days, nevertheless, that does not make it less real.

Consider the aesthetic pressure that we face daily as women: about our lifestyles, relations and health. Publicity, marketing or songs are just another type of gender violence: they present an ideal of beauty and behavior that influence the way we live, even causing severe health problems as anorexia or bulimia (for example, 26.000 Catalan teenager girls suffered from anorexia or bulimia just in 2013).

Consider also the role of sex and the use of a woman’s body. In Gilead, sexuality is hidden in the name of immorality. But we live in the other extreme: the abuse of women’s sexuality and the idea that part of the reproductive labour of women is to gratify the sexual desires of man, do not just happen in spaces as Jezabel’s, the prostitution night club of Gilead, but in all life’s spheres. A woman who was a prostitute before Gilead and now is a handmaid, feels better in Gilead. She is safe; she does not need to sell her body to survive. Patriarchy has pornographized women sexuality. Almost every kind of sexual expression or sexual representation is modeled on it. Indeed, the voice of pornography – sexually explicit material with the primary purpose of arousal – is the voice of the ruling power: women are sexualized, subordinated, objectified and degraded as a consequence of man’s ideas of sex rights and our sexuality is celebrated just as a mechanism of control.

In Gilead, women and especially the handmaids are expropriated of their reproductive rights. But let us not be so proud of our record. Just 56 countries today – representing 39% of world’s population – contemplate the right to abortion without restrictions. 26% of all people in this planet reside in countries where abortion is prohibited under all circumstances.

The danger of picturing a dark future, following some sort of cataclysmic event, can make us complacent to think that we are fine now. The last thing we need now, as women’s rights are attacked on all fronts, is to perpetuate a state of meekness by not challenging the present. Reactionary positions are more and more common, but only if we do not confront the current situation, it is not unlikely that Gilead becomes a reality.

Júlia Hosta Cuy is a Master’s student of Ecological Economics at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Reblogged this on Political Ecology Network.