by Eric Pineault

A fascinating aspect of Jacobin’s Earth Wind and Fire issue is the obsessive “presence of the absence” of Degrowth, of limits and the critique of scale. When mentioned, Degrowth is evoked to further convince the reader of the necessity and reasonableness of green Keynesianism and accelerated centrally planned solar communism. Writing after several prominent ecological and marxist thinkers that have produced thorough critiques of Jacobin’s ecomodernism, I want to explore this absent presence.

Editors’ note: This is the first part of the fourth post in a series of ENTITLE blog articles that critically engage with the ongoing discussions about “eco-modernist socialism” and “communist futurism”, projected in Jacobin magazine’s climate change issue ‘Earth, Wind, and Fire.’ Our series continues the debate with critical insights that question the foundations of these proposals. In particular, whether they imply a substantive transformation of current capitalist socio-ecological regimes, or their continuation and even expansion. The series had featured posts by Aaron Vansintjan and Stefania Barca, and Emanuele Leonardi.

I’m interested in how the spectre of Degrowth haunts left ecomodernism as something unimaginable; how it works to foreclose certain avenues of radical thought and practice. This first entry will focus on the foreclosed critique of the “growth is good” ideologeme. I will explore in a second post the consequences of an ecological materialism and the foreclosure of transition as a scaling down of social metabolism.

A colonized imaginary

One of the founding gestures of Degrowth was a call for the “decolonization of the imaginary” of those critiquing capitalism and debating the contours of a post-capitalist society. Growth is a central structure of modernity’s imaginary of progress. In this imaginary, economic growth acts as the material foundation of individual (liberal) and collective (socialist) emancipation from want and need, emancipation being a central normative principal of these conceptions of society. And thus a critique of growth is immediately received by progressives as a critique of material emancipation. Put more forcefully, a call for limits to growth cannot be received as anything other than a demand to limit emancipation by institutionalizing material wants and scarcity. No matter how subtle and convincing the scientific or rational argument for limits to growth, it will be received with a “pre-analytic” visceral reaction of foreclosure. And this is because in modern society, economic growth and its material consequences are natural, progressive, and act as a principle of historicity, meaning a way we understand our collective trajectory. Economic growth thus understood is highly different from both the common sense understanding of growth and its counterpart in the biological sciences. In both these cases growth has a beginning – birth- and an end – maturity. Furthermore, growth is not an objective, it is a means to an end – being “grown up”.

So where did modern society find its curious conception of economic growth? One can trace it to many sources, but here I want to return to the way it was weaved together by Adam Smith. The way he “naturalized” economic growth as emancipatory and progressive has had a lasting impact not only on economic thought but on the social imaginary of socialists as much as liberals. There is much of Smith’s theory of the “Progressive State” that has found its way into “Think Big Ecosocialism”, Jacobin’s proposed working class alternative to moralistic, middle-class, “small is beautiful” environmentalism. Think Big Ecosocialism rests on a few key principles: a democratic alternative to capitalism implies state-centric socialism with large-scale planning, big public infrastructures, and massified but socialized relations of production and of consumption. Modernity’s technosphere must be domesticated but not dismantled, its high tech innovations contain potentially revolutionary forces of production and of social coordination that capitalism has not yet fully developed.

The Progressive State as the foundation of growthism

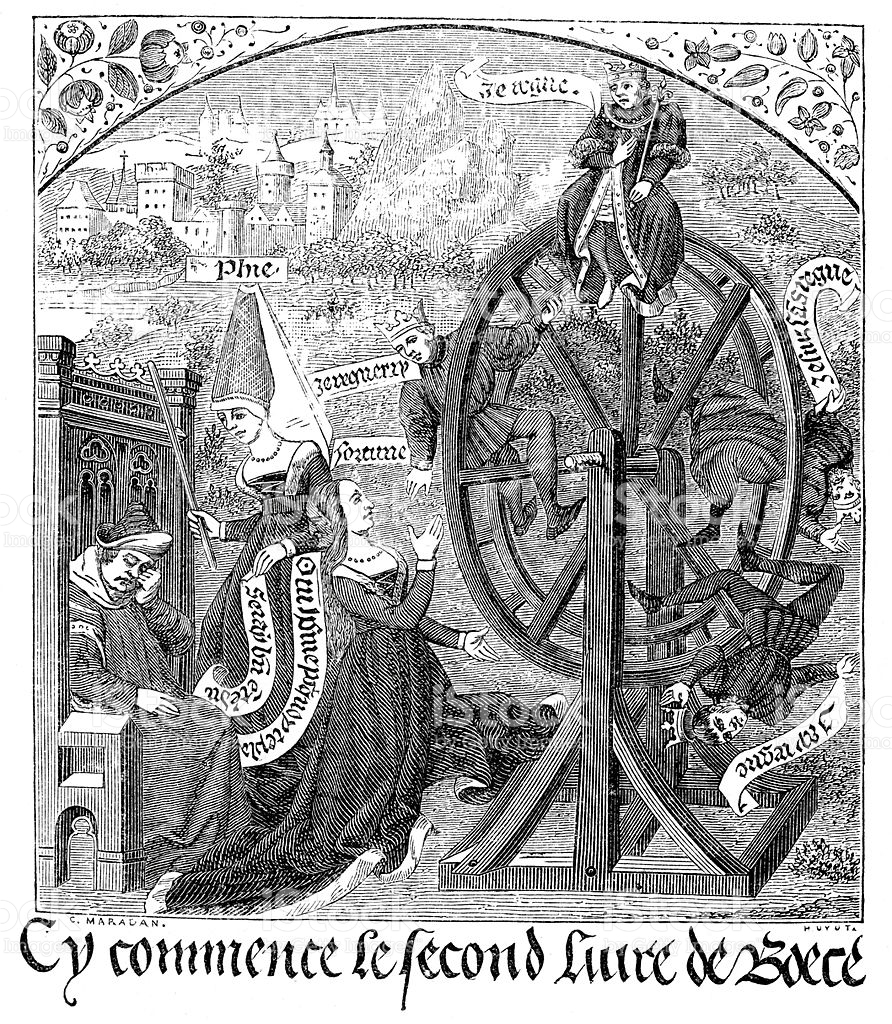

In the Wealth of Nations Smith defines the Progressive State as one of three possible states of an economy, alongside the Stationary State and a State of Decline or decadence. Smith is working with images that are typical of the ancient “Wheel of Fortune” that was a common representation of history in social and political thought from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Cities, Empires, Nations and Kingdoms rose to prominence, extended their power and attained a state of grandiose maturity, prosperity and wealth, after which they where fatefully pushed by the forces of fortune to decay and death, while new powers arose elsewhere. “Hubris” here plays a central and defining role, it was the transgression of limits that set the hegemonic power down the road of decline and crisis. For religious philosophers it was impiety, for a secularist Machiavelli it was corruption, for the republican Rousseau it was avarice and luxury. This deep sense of historicity went through a complete metamorphosis in Smith’s economic theory of growth. From successive stages in the wheel of fortune and fate each stage was redefined as types of economies that could exist in parallel one to another. Economic growth was not a stage towards maturity it became a form of historicity.

In Smith’s mind, not only was it possible for a nation to remain indefinitely in the Progressive State; it was the duty of a liberal government to ensure so. From the standpoint of history as a wheel of fate, this was a curious and even hubristic proposition. With Smith it is as if society was condemned to an endless quest of material expansion, but in doing so Fate and Fortune’s fickle will could be cheated and decline and decay avoided. A treadmill replaced the wheel of Fortune, Accelerationism’s playbook was written.

Value and the capture of Physis

Value in economics explains both the the allocation of productive potential and distribution of social wealth, and in Smith’s Progressive State the first was efficient and the second was just. Smith’s concept of value was heavily influenced by the Physiocrats. They where the first economic thinkers to break with the mercantilist world view of the economy as a zero sum game and develop the idea of an economic surplus. But for them, value, the source of material surplus, remained outside of society’s grasp. It resided in Nature, “physis”: the unlimited productivity of the earth captured by agriculture and extractive industries. Only by obeying (cratein) the laws of nature (physis) could nations grow their economies, and capture and direct the natural surplus to socially-defined ends.

In Smith’s important twist, physis, the naturalized cause of wealth, became human labour: divisible, ameliorable, exploitable. But only that part of human labour that was “emancipated” from the labours of the sphere of reproduction was deemed bearing value, other activities were “necessary but barren”, “unproductive”. And nature? Nature was reduced to a simple “giver of gifts” to society. Value and surplus were strictly social and gendered. Physis was transfigured in this “a-biophysical” but naturalized theory of value: productivity rested on the division of (waged) labour combined with the mobilization of technological innovations. The Progressive State was a self-perpetuating trajectory of growth that rested on social foundations: labour and technology. What Marx would later conceptualize as “forces of production”.

Smith’s Progressive State can rightly be considered a foundational structure of the economic imaginary of modern – capitalist society. In it, emancipation, progress and growth are weaved together. Emancipation as freedom from wants and constraints, equality as a fair share of social wealth, and material progress as technological innovation and greater labour productivity were together intimately tied to economic growth, and growth to history. Nature? Invisible. Growth? A necessary trajectory and the natural state of a “progressive society”. Without growth, society is condemned to reenter the cyclical wheel of fate and faces the prospect decline and death. Unimaginable.

Eric Pineault is a professor at the University of Québec in Montreal. He teaches political economy at the Department of Sociology and Ecological Economics at the Environmental Sciences Institute. His research focuses on the growth dynamics of advanced capitalism as well as on extractive capital and extreme oil in Canada.

Left Should Stop Equating Labour With Work

https://www.socialeurope.eu/why-work-not-labour-is-ecological-imperative

Reblogged this on Political Ecology Network.

Like much discussion of growth and degrowth, this analysis fails to properly define what “growth” is. Namely, it fails to make the crucial distinction between GROWTH (the increase in value produced) and THROUGHPUT (the material consumption of nature and the discharge of pollutants into the biosphere). Throughput is inherently bad and must be dramatically and immediately reduced. Growth, however, is not inherently bad, and CAN occur without increasing throughput — most current economic growth is very throughput-intensive, but that need not be the case. This distinction is crucial not just for ecological reasons but also for political and economic reasons. We need growth, as well as redistribution, to eliminate poverty. Any ecologist platform that fails to recognize that imperative will limit itself to a mainly middle-class constituency. And it does so unnecessarily, since it’s entirely possible for most of the world’s people to live much more comfortable lives via growth and redistribution while also averting ecological catastrophe. For more explanation see http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/36723-ecologically-sustainable-growth-is-possible-an-interview-with-robin-hahnel.