By Carmelo Ruiz*

The region’s progressive governments are hardening their positions in favour of mining and oil extraction and against civil society environmental organizations and other critics of extractivism.

The recent threats against non-governmental society organizations (NGOs) made by the avowedly progressive and environmentally-minded governments of Ecuador and Bolivia have caused commotion and discussion among academics and activists in both North and South. Last August, Bolivian vice president Alvaro García-Linera, a highly esteemed Marxist intellectual, singled out four NGOs for retaliation if they continued their “political work”. A number of high-profile international intellectuals called on García-Linera to rethink his stance.

But rather than reconsidering, the region’s progressive governments are hardening their positions, judging from the speeches delivered at the second Latin American Progressive Encounter (ELAP 2015) hosted by the Ecuadorian government in the capital city of Quito in September 28-30. The event, which had the participation of tens of political parties and movements from Latin America and Europe, featured keynote addresses by García-Linera and Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa, precisely the two public figures that have led the charge against Latin American NGOs from the left.

The political line that emanated from ELAP 2015 with respect to natural resources and extractivism bears close examination because of the event’s timing. It took place right at the end of the United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York City, in which both Correa and his Bolivian counterpart Evo Morales participated. Also, the ELAP took place less than two weeks before the second international civil society meeting on climate change in Bolivia, hosted by president Morales. At this activity in Bolivia, Latin American progressive governments, with the help of select civil society actors, hope to hammer out a common position on climate change for the COP 21 meeting in Paris later this year.

Correa on NGOs and “infantile ecologism”

46 minutes into his ELAP keynote, Correa started to go over his list of “errors” of the left. First on the list: el ecologismo infantil (infantile ecologism). This is the epithet he often uses to describe those who believe “that in order to be considered in the left one has to say ‘no oil’, ‘no mining’, ‘no exploitation of our natural resources’.”

If we followed their advice, the whole political project in Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia, Chile, and other countries, would collapse”, said Correa.

He continued arguing that “There are now some supposedly radical groups, ecologists of the left that consider (man) to be an obstacle to nature. The human being is not the only important thing in nature, but it is the most important”, summarizing his view of the environment versus development dilemma. “We must take care of nature, but take care of it so that it can keep on giving fruit, in order to overcome poverty, to achieve el buen vivir (right livelihood).”

Correa then launched what was undoubtedly a broadside against his former colleague Alberto Acosta: “A confused individual, supposedly an intellectual of the left, said that oil is a curse. Of course it is a curse, if it is managed by the partidocracia (traditional political parties), corrupt hands, the Chevron corporation, or insensible governments.”

Acosta, an economics professor with a long history of association with the left and the ecology movement, was, along with Correa, among the founders of the ruling Alianza PAIS party. He went on to chair the constituent assembly that wrote a new constitution for the country, a constitution which is one of the most advanced in the world in matters of environmental protection and citizen participation. But soon afterwards, Acosta went over to the opposition and decried the new progressive government’s extractivist policies. In 2009 he published La Maldición de la Abundancia (The Curse of Abundance), in which he argues that non-renewable resources have historically been nothing but a curse for developing countries.

But (oil) can be a blessing, and in fact it is. The natural resources of Latin America can be a blessing if they are managed in the interests of the majorities. Our non-renewable natural resources, like mining and oil, are the great opportunity, the great advantage for Latin America to achieve development… (These resources) afford us a great strategic value at a worldwide level.” (Raphael Correa, ELAP 2015)

He dismissed Ecuador’s environmental problems, arguing that these are absolutely infinitesimal when put in a global context: “We are marginal polluters. In (global) CO2 emissions we are responsible for 0.1%. The big polluters are others. We are all responsible for caring for the planet, but this takes us to the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities. We in the poor and middle income countries are not the ones polluting the planet. On the contrary, we generate bienes ambientales (environmental goods). It’s others who pollute and consume those environmental goods without paying for them… Let’s not be dupes of the major polluters. We need our natural resources in order to overcome poverty.”

Correa presented Ecuador’s Socio Bosque program as a workable alternative for environmental justice, but did not seem aware of the controversy around this program. Socio Bosque is subordinated to the U.N.’s REDD mechanism, which has been condemned as a failed form of green capitalism by numerous environmental groups, including the Global Justice Ecology Project, CENSAT Agua Viva, the ETC Group, the World Rainforest Movement, Amazon Watch, and Ecuador’s Acción Ecológica. Furthermore, Socio Bosque is administered by Conservation International, a well-funded NGO that receives funds and has close partnerships with major oil companies, as well as a close working relationship with the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the same US government agency that Correa expelled from Ecuador for being a tool of imperialism.

Correa went on to contrast the privatization of knowledge with the free use of the global South’s environmental goods by the world’s powerful, and argued that it should be the other way around: that knowledge should be free while environmental goods, which are mostly in the countries of the South, should be used only after paying just compensation: “Why is knowledge privatized while environmental goods are freely consumed?”

This argumentation forms the core of his proposal for a knowledge economy, powered by innovation in science and technology rather than by the bulk extraction of non-renewable resources. But, how can this knowledge economy be reconciled with the Ecuador-European Union free trade agreement (FTA) that he is pursuing? The agreement’s text has intellectual property provisions that would enable the privatization of Ecuador’s biodiversity. What sovereignty, what high-tech knowledge economy can the country have after the FTA with the EU enters into effect?

New publication by Acción Ecológica analyzes recent treaties signed between Ecuador and the EU, and their implications for food sovereignty and small agricultural producers.

Yet Correa is not concerned with the FTA. To him the only real obstacle to the knowledge economy are the infantile ecologists, who must be vanquished: “Let’s overcome this infantile ecologism which has caused us so much harm. It would have us immolate ourselves so that others can keep on polluting.”

Correa went over other “errors” of the left, including “infantile indigenism” and “infantile leftism”, before attacking NGO activists in general, whom he described as losers who cannot win elections: “They normally lose elections, those who appoint themselves representatives of civil society. They legitimize some NGOs… that engage in politics without political accountability. They are financed by far right groups in the hegemonic countries, in order to do politics and destabilize the region’s progressive governments.”

García-Linera’s advocacy of (temporary) extractivism

García-Linera also had words on the extractivism debate. Judging from his tone whenever he said “extractivism”, it is evident that he dislikes the word. It is a word that has been successfully introduced into the Latin American political debate by forces that he considers antagonistic to his revolutionary project, and now he has no choice but to use it. To the Bolivian vice president the mere use of the word is a necessary evil, for it can suggest an implicit endorsement of the views of the ecologistas infantiles.

García-Linera pointed out that extractivism is nothing new in the region, that it goes back to the earliest years of the Spanish conquest. But given Latin America’s extreme poverty, argued the vice president, it is necessary to use extractivism, albeit temporarily, in order to provide urgent relief to the poor. “If devote ourselves only to caring for nature, we will remain in poverty.”

Yes, we do have to get out of extractivism. But that is not achieved by freezing the conditions of production or by returning to the stone age… We employ extractivism temporarily in order to create the cultural, organizational and material conditions of the population in order to leap to the knowledge economy.” (Alvaro García-Linera, ELAP 2015)

Bolivian vice president Alvaro García-Linera during his keynote speech at ELAP 2015 in Quito, Ecuador. Source: elapecuador.com.

García-Linera is particularly irked by the fact that the critics of extractivism are mostly from the political left. He took a swing at them, describing them as the “lactose-free coffee house left” that is “perfumed and well paid”. Sparing no insult, he then went on a verbal rampage. The members of this left, he said, are “accomplices of the neoliberal past, which have now become ultra-radical prophets of the imminent failure of the revolutionary processes… They have no concrete measures, not a single practical proposal to advance the revolutionary processes” … They are part of “the new imperial offensive that seeks to destabilize progressive processes and governments. Their abstract inoperant pseudo-radicalism (reflects) the conservatism and racism of well-to-do sectors that under the camouflage of a pseudo-leftist and pseudo-environmental discourse seeks to discredit the revolutionary processes.”

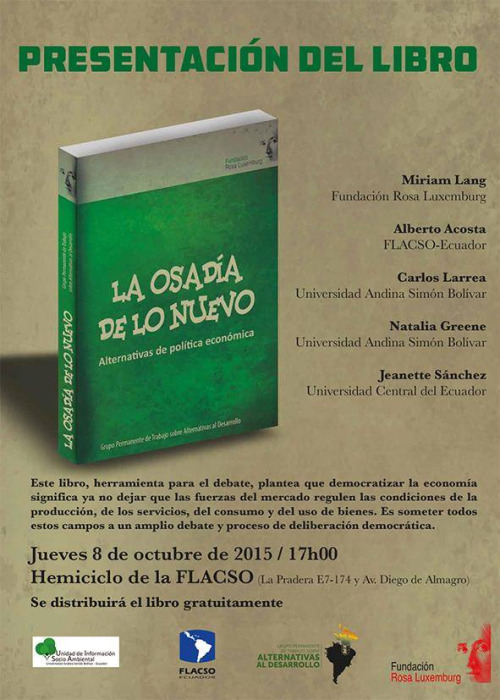

The notion that their leftist and ecologist critics offer no alternatives or proposals is a frequent theme in the discourse of the Bolivarian progressives. However, such a statement can only be made by ignoring the abundant literature of analysis, discussion and alternatives to extractivism produced in recent years by FLACSO (Latin American Social Sciences Faculty), NGOs like Acción Ecológica and CEDIB, and intellectuals like Joan Martínez-Alier, Eduardo Gudynas, Raúl Zibechi and Alberto Acosta. Just one week after the ELAP, right in Quito, a new book on economic policy alternatives, La Osadía de lo Nuevo (The Audacity of the New), was presented at FLACSO.

At least they cannot ignore us

What was more unsettling and disturbing than the confrontational language, intransigent postures and slew of epithets on the part of Correa and García-Linera was the fact that their tirades against environmentalists and the critical left received the loudest rounds of applause from the enthusiastic audience. The outcome of ELAP only heralds more confrontation and hard times for Latin American defenders of the environment and intellectuals that are critical of extractivism.

But on the on the other hand, the political and intellectual leaders of the new Latin American progresismo have found it impossible to suppress the debate. The powerful political, intellectual, academic and media tools at their disposal have been insufficient to bury the critical voices. For all their triumphalism and verbal swagger, they are constantly on the defensive, compelled to defend their model at almost every speaking engagement.

The debate is on, and the progresistas bolivarianos cannot stop it.

*Carmelo Ruiz is a Puerto Rican author and journalist. He is a research associate of the Institute for Social Ecology and a senior fellow of the Environmental Leadership Program, and directs the Latin America Energy and Environment Monitor. His Twitter ID is @carmeloruiz.

One Comment