by Gustavo Garcia Lopez and Salvatore Paolo De Rosa

Note: This is the fourth of a five-part entry on the Tales from Planet Earth film festival held on April 9-12 in Stockholm, Sweden (to see the previous entries go HERE, HERE, and HERE). The Festival was organized by ENTITLE member Professor Marco Armiero, director of the Environmental Humanities Laboratory at the Swedish Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), in cooperation with ENTITLE.

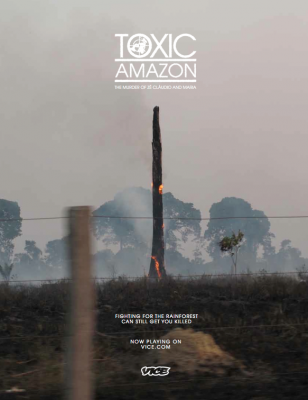

If the circumpolar north offered a largely depoliticised view of majestic landscapes, the last day of the Festival presented a fitting contrast of highly political toxic landscapes through two excellent films, Wasting Naples(Nicola Angrisano collective, 2009) and Toxic Amazon (co-produced between Felipe Milanez –ENTITLE PhD fellow at Coimbra University– and VICE, 2011), which made for a great conclusion to the festival. Both show us what we mean by the political in ecology, both in terms of politicising nature and of the political struggles to defend it from capitalist processes of accumulation.

Wasting Naples offers a powerful example of slow violence and of the ways the cooperation between the State and the private sector treats certainpeople and ecologies as disposable. The documentary is also an example of a process of making films by and for social movements rather thanabout these movements: it was produced collectively through dozens of sections of footage captured by different activists during some of the harshest battles, and then assembled by Insu_tv media-activists, who also complemented it with interviews of movement members and experts. The film tracks the fifteen-year long “waste crisis” in the Campania region of southern Italy, from the declaration of the “state of emergency” by the government in 1994 to the official inauguration of the highly contested waste incinerator in the town of Acerra in 2009. The crisis started as the result of the misuse of regional landfills, illegally filled beyond their capacity and thus unable to handle all the urban waste being generated. On the one hand, we see how the government’s inept and corrupt response to this crisis: a “state of emergency” that supposedly had to reclaim thewaste management from the hands of criminal organisations ended up in favouring the same Camorra actors and a private company to which the entire waste management sector was entrusted. This led to an ever-worsening situation which ultimately helped justify lifting the application of environmental laws and fast-tracking the permits for incinerators and new landfills. This was imposed by the government in socio-economically deprived areas, already burdened by pollution, in towns of the plain where agriculture thrives and even inside supposed nature preserves. In this way, revenues for the private company and for the owners of waste facilities andtrucks (often linked to Camorra) were maximised, without any concern for the health and environmental contamination risks for local communities.

Wasting Naples offers a powerful example of slow violence and of the ways the cooperation between the State and the private sector treats certainpeople and ecologies as disposable. The documentary is also an example of a process of making films by and for social movements rather thanabout these movements: it was produced collectively through dozens of sections of footage captured by different activists during some of the harshest battles, and then assembled by Insu_tv media-activists, who also complemented it with interviews of movement members and experts. The film tracks the fifteen-year long “waste crisis” in the Campania region of southern Italy, from the declaration of the “state of emergency” by the government in 1994 to the official inauguration of the highly contested waste incinerator in the town of Acerra in 2009. The crisis started as the result of the misuse of regional landfills, illegally filled beyond their capacity and thus unable to handle all the urban waste being generated. On the one hand, we see how the government’s inept and corrupt response to this crisis: a “state of emergency” that supposedly had to reclaim thewaste management from the hands of criminal organisations ended up in favouring the same Camorra actors and a private company to which the entire waste management sector was entrusted. This led to an ever-worsening situation which ultimately helped justify lifting the application of environmental laws and fast-tracking the permits for incinerators and new landfills. This was imposed by the government in socio-economically deprived areas, already burdened by pollution, in towns of the plain where agriculture thrives and even inside supposed nature preserves. In this way, revenues for the private company and for the owners of waste facilities andtrucks (often linked to Camorra) were maximised, without any concern for the health and environmental contamination risks for local communities.

Through incineration, waste is literally made invisible but it does not “disappear”: highly toxic nano-particles are generated and pumped into the atmosphere. The health and ecological consequences are hidden due to the time they require to fully manifest themselves into the bodies and ecologies where they accumulate – slow violence is, as Rob Nixon explains in his book, “the violence of delayed effects” (p. 128).  Furthermore, slow violence is also the effect of the relentless seeking of maximum profitability by the private company, backed by the government, that led to the amassing of million tonnes of packaged waste in Campania: every one of these blocks, scattered still today throughout the region, represented infact the insurance of revenues thanks to the public subsidises for incineration.

Furthermore, slow violence is also the effect of the relentless seeking of maximum profitability by the private company, backed by the government, that led to the amassing of million tonnes of packaged waste in Campania: every one of these blocks, scattered still today throughout the region, represented infact the insurance of revenues thanks to the public subsidises for incineration.

On the other hand, we see the citizens’ resistance in their attempt to make all this visible, and to not submit (or as Foucault would say, to be governmentalised) to the profit-driven sacking of their ecology and their health. As a sign in a camp blocking the entrance to one of the proposed landfills read: “we will never be like you want us to be”. During the protests, we see the heterogeneity of participants and we listen to their concerns and critiques: rather than the effect of a “Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY) syndrome, as spread by media and politicians, the opposition to top-down waste management plans and to Camorra’s free-hand exploitation is framed by people as a resistance against the turning of bodies and ecosystems in means for profit. The entire waste plan is politicised and debunked as a path for profit-seeking management, hidden by discourses of technological and modern “solutions”. At the same time, the governance applied by the government, legalising any kind of derogation from environmental laws, is exposed as political prostration toward economic interests. In the film, we also see the response of the government to the increasing social unrest: the tightening of repression with the consequent militarisation of the new areas proposed for landfills (declared areas of national interest) and the criminalisation of protests. Thus, as ENTITLE member Giacomo D’ Alisa and colleagues have written in the journal Ecological Economics, this is an example of how this is not really a waste crisis, but a crisis of democracy, with the subsequent suppression of alternative views and values about how to manage waste and conceive urban planning and democratic process. In fact, in a recent piece published in Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, D’Alisa and Armiero show that the waste crisis was managed through a permanent state of emergency or exception –where environmental and other laws are suspended and protest is criminalized– “to support private interests and disempower democratic participation”.

Toxic Amazon tells the powerfully moving story of the murder of two activists, Zè Claudio and his wife Maria, who fought to protect the forest from illegal logging, ranching and coal in their village. Zè Claudio is the embodiment of the environmentalism of the poor. We learn that he had been a nut gatherer (castanheiro) since he was 7, and that this is his mainmotivation for having started to protect the extractive forest from illegal loggers. The movie then situates these murders in the context of two processes. One is the broader struggles for land reform that have been at the centre of Brazilian politics for decades (we learn that a proposed land reform was one of the reasons of the coup d’état in 1964), and the associated violent repressions, such as the assassination of Chico Mendes and, in a separate incident, of nineteen activists from the Landless Peasant Movement (MST). The struggles in the Amazon, the film explains, are not so much between man and nature but between rich and poor, not so much about environmental conservation but about land reform. In other words, they express manifestations of political ecology.

Toxic Amazon tells the powerfully moving story of the murder of two activists, Zè Claudio and his wife Maria, who fought to protect the forest from illegal logging, ranching and coal in their village. Zè Claudio is the embodiment of the environmentalism of the poor. We learn that he had been a nut gatherer (castanheiro) since he was 7, and that this is his mainmotivation for having started to protect the extractive forest from illegal loggers. The movie then situates these murders in the context of two processes. One is the broader struggles for land reform that have been at the centre of Brazilian politics for decades (we learn that a proposed land reform was one of the reasons of the coup d’état in 1964), and the associated violent repressions, such as the assassination of Chico Mendes and, in a separate incident, of nineteen activists from the Landless Peasant Movement (MST). The struggles in the Amazon, the film explains, are not so much between man and nature but between rich and poor, not so much about environmental conservation but about land reform. In other words, they express manifestations of political ecology.

The second process associated with the murders of Zè Claudio and Maria is the expansion of capitalist extractive activities. As a lawyer from the Pastoral Land Commission reminds us in the documentary, this “exploitative model of development” inevitably leads to violence. Locally, the system is supported by ‘timber thieves’, labourers in slave-like conditions, and armed mafias. But it is not these local timber loggers who really benefit from the system; they are merely intermediaries for the large landowners and the corporations that reap the profits. It is, as Nixon calls it, a new form of “colonial buccaneering” or “organised brigandage.” At the same time, the process of extraction is also connected to global markets where rich countries buy the illegal timber from the Amazon (90% of all timber in the Amazon is illegal). As a federal police officer laments, there is no point enforcing the environmental laws in the Amazon when the US and Europe are paying $10,000 dollars per cubic metre of timber.

At the national level, this vision of progress is embraced by the so-called Ruralista movement in Congress. This vision completely disregards the lives of those who oppose this hegemonic economic model, as dramatically expressed by a Ruralista Congressman from Pará, according to whom all of those who oppose their vision – including activists – “are abusing, so we have to exclude them from Brazilian society…they don’t contribute to the reduction of poverty.” In other words, they don’t have a right to be Brazilians because they have a different vision of progress. In another powerful scene, the Ruralistas boo and laugh at a Congressman and leader of the Environmental Party when he gives a speech in Congress to inform and denounce the murder of Zè Claudio and Maria.

In their interviews just two months before their death, both Maria and Zè Claudio expressed their fear, recognising that it was a very unequal fight between environmentalists and the power of money – in other words, capitalism. But at the same time, they also made clear their resolution to continue fighting. Zè Claudio was convinced that this was his duty as citizen, and that ‘it was better to die fighting than to die in neglect’. In other words, to Zè Claudio, not resisting would have meant not existing at all. The struggle was an integral part of his life. In their funeral procession, activists and family members shouted that despite his death, his struggle would live on. Ken Saro-Wira, the Nigerian activist condemned to death by the dictatorship in his country for opposing oil giant Shell’s destruction of the Niger Delta and its communities, said the same thing after the trial’s verdict: “I will tell you this, I may be dead, but my ideas will surely not die.”

Coincidentally, a few days after the screening of Toxic Amazon, the NGO Global Witness released a report on the killings of environmental activists across the world. The report documented the case of Zè Claudio along with hundreds of others, showing how extractivist activities from large corporations, or complacent or corrupt states, were the main driving factors behind these murders. In it, we found another echo of Zè Claudio’s words about struggle, courage and neglect in one of his predecessors in the struggle to protect the Amazon and the livelihoods of those who depend on it, Chico Mendes: “At first I thought I was fighting to save rubber trees. Then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest. Now I realise I am fighting for humanity.”

Coincidentally, a few days after the screening of Toxic Amazon, the NGO Global Witness released a report on the killings of environmental activists across the world. The report documented the case of Zè Claudio along with hundreds of others, showing how extractivist activities from large corporations, or complacent or corrupt states, were the main driving factors behind these murders. In it, we found another echo of Zè Claudio’s words about struggle, courage and neglect in one of his predecessors in the struggle to protect the Amazon and the livelihoods of those who depend on it, Chico Mendes: “At first I thought I was fighting to save rubber trees. Then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest. Now I realise I am fighting for humanity.”

Some thoughts on film, activism and research from the final day’s roundtable

The Film Festival provided a window to reflect on the role of documentary cinema in political and ecological change, and an opportunity to ENTITLE to bring forth a political ecology perspective on the movies and related discussions. In a reflection on the relationship between film, political ecology research, and activism, Professor Armiero led a very engaging roundtable discussion on the last day of the Festival with Nicola Angrisano from Insu_tv collective, and ENTITLE members Felipe Milanez (Coimbra University), Dr. Giacomo D’ Alisa (Autonomous University of Barcelona) and Professor Stefania Barca (Coimbra University). To stir the debate, Professor Armiero posed the following questions, which we share here for our readers to reflect on: How it is possible to do politics and activism in movies? What is an activist? How can we change the academic world and what room there is for radical? How do activists react to be objects of movies and how can we make them subjects?

The roundtable discussants as well as audience members provided different perspectives on these questions. There is not one single correct way for engagement and integration of art, activism, and research, but multiple ways from being a pure activist and doing art from within a movement or struggle (as the collective making Wasting Naples), journalists who do not see themselves as activists but still feel as part of the movement, participating observers who have been activists bt are now scholars and maintain ongoing engagements, to those who have always been scholars and are collaborating and conversing with activists from academia.

One of the keys to the integration of activism and research is coproducing knowledge on an equal level, as highlighted by Professor Armiero. Professor Barca gave the example of militant scientists in Italy who collaborated with workers to do a research project on the health impact of petrochemicals (i.e., popular epidemiology). She reminded us that a lot of research is inherently political because of the implications of the stories we tell, particularly when challenging hegemonic narratives. This is precisely how political ecology started –challenging conventional narratives about environmental degradation that attributed it to marginalized resource-dependent peoples, and instead looking at power, political economy and history. These critical engagements help breaking down naturalization of ideas, and could potentially empower people with an alternative set of memories, a repertoire of possibilities outside hegemonic, for instance, that there are no alternatives to neoliberalism.

At the same time, it is important to highlight, as D ‘Alisa and colleagues have emphasized in their analysis of different movements for alternatives to growth-based societies, there is broad heterogeneity amongst activists, which can be categorized into the more professionalized NGO-type, reformist civil society, and the more rebellious, critical, anti-systemic “uncivil” society. Moreover, in his autobiographic analysis of water conflicts in Naples, D’Alisa argues that within uncivil society, one can further distinguish between compañeros (those who not only share ideology but also deeper ties of friendship or even an extended family, and who engage in “commoning” projects) and militants (who limit relationships to the struggle). Militants ask what has to be done, they have a clear ideological narrative, whereas compañeros raise not only what has to be done but also how it has to be done, not just ideological aim but also the process of sharing in a movement.

For those of us interested in being “organic intellectuals”, it does not mean being intellectual leaders of a movement, but rather critically reflecting on academia, on the limitations and spaces for action, and on the challenges of the radical politics we believe in. In this sense being from outside can have advantages. When we are too engaged emotionally with a movement, it becomes increasingly challenging to be critical; moreover, it is hard for the movement to welcome that criticism when one is an academic even if one believes to be an activist.

The discussion in the roundtable also highlighted that there are many challenges in becoming engaged, including state and corporate repression, being criticized as not being ‘objective’ in our professions (journalist, academic, filmmaker), academia’s pressure on professors to obtain grants and publish in journals, and the positioning of oneself in an often-uncomfortable and ill-defined space between an academic and activist where one is both and at the same time is neither. However, what became clear in the end is that indifference is not an option.

In this context, an open question is whether film and other types of artistic endeavors linked to activism and research “can cause enough indignation to incite transformative change”. Felipe Milanez and Nicola Angrisano highlighted how filmmaking provides the possibility to share experiences and voices, regardless of whether one is an ‘activist’. It also provides a mechanism to breaking down isolation between movements, as activists can see themselves in other struggles. In a recent article, Mark Karlin argues that to achieve this transformative potential, (radical) art cannot be “caged in a museum”, needs to be anti-hierarchical, challenge dominant understandings of society while being understandable to the population at large, and integrated with the community as interactive participants in the process of artistic creation. It requires, in short, to shed indifference and engage with the process of art-making as “an act of uncompromising passionate resistance”.

One Comment