CEDIB is one of the Bolivian organizations which have come under attack for critiquing the government’s extractivist policies—Carmelo Ruiz* interviews Marco Gandarillas, its excutive director.

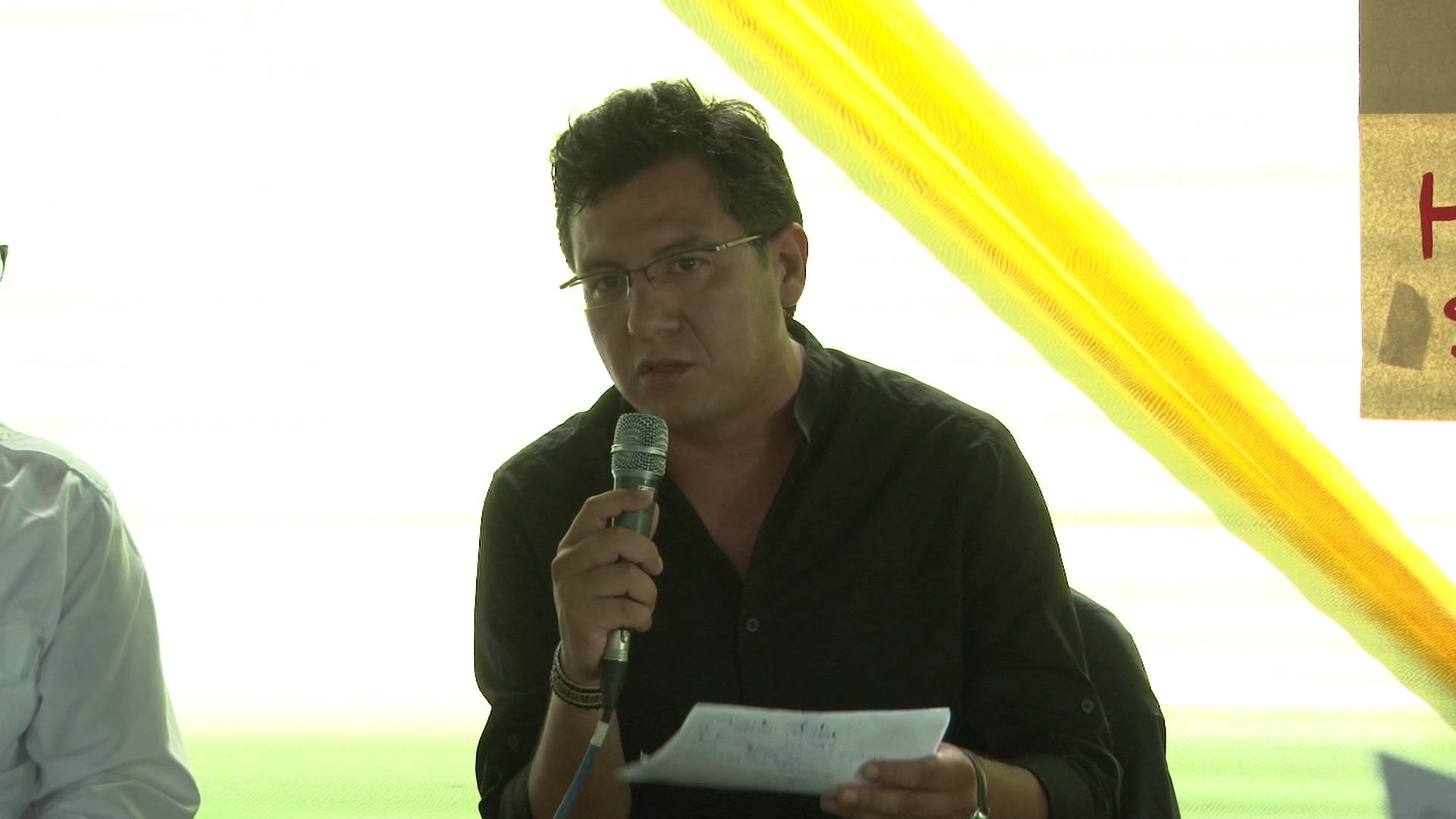

Marco Gandarillas, Executive Director of CEDIB. Source: es.panampost.com.

(Para la versión original de esta entrevista en español, publicada en ALAI.net, pulse aquí)

Back when neoliberalism reigned supreme in Latin America, the dominant discourse classified non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that worked for environmental sustainability, human rights and community development as leftist forces and even as vehicles for Chavismo. Since the late 1990s, some of the neoliberal Latin American governments have been replaced by a new political leadership that describes itself as progressive, Bolivarian and even socialist. These new left-leaning governments accuse now those same NGOs of being imperialist and colonialist. This despite of the fact that the work and discourse of these organizations has not changed.

No Latin American intellectual or political figure has devoted more time and effort to articulate the “NGOs = imperialism” equation than Bolivian vice president Alvaro García Linera. From the office of the vice presidency he published two books in 2011 and 2012, in which he elaborates on his thesis that NGOs are enemies of the sovereignty and progress of Latin American peoples (1).

Quoting from the second of these books, Geopolítica de la Amazonía (Geopolitics of the Amazon):

NGOs have been able to establish a clientelist relationship with the indigenous leadership… to the extent that these levels of organization, with scarce contact with the Amazonian indigenous grassroots, function exclusively with external financing which pays for the leaders’ salaries… (they) reproduce mechanisms of clientelist co-optation and ideological and political subordination towards funding agencies, which are mostly European and North American, as in the case of USAID (p. 26).

If in first world countries, NGOs indeed exist as part of civil society—in most cases funded by transnational corporations—in third world countries, as in the case of Bolivia, some NGOs are not really NON Governmental Organizations, but rather Organizations of Other Governments in Bolivian territory; they are a replacement of the state in areas in which the neoliberalism of the past arranged for its departure, reaching even sectors like education (through privatization attempts or charter schools) and health (for example Prosalud (USAID)). The NGO, as organism of another government and as provider of financial resources, defines the framework, the approach, the funding scheme, etc. from those priorities of that other government, constituting itself as a foreign power within the national territory (p. 27).

… Some NGOs in the country have been the vehicle for the introduction of a type of colonial environmentalism that relegates indigenous peoples to the role of caretakers of the Amazon forest (considered extraterritorial property of governments and corporations creating a de facto new relationship of privatization and denationalization of national parks and community lands, where the state has lost tutelage and control. In this way, whether by way of the strong domination of the hacienda’s despotism, which controls the processes of intermediation and semi-industrialization of Amazon products (lumber, lizards, nuts, rubber, etc.) or by way of the soft domination of the NGOs, Amazonian indigenous nations are economically dispossessed of the territory and politically subordinated to external discourses and powers. In summary, economic and political power in the Amazon is not in the hands of indigenous peoples or in the hands of the state. Power in the Amazon is in the hands of a hacienda-business elite as well as foreign companies and governments that negotiate the care of Amazon forests in exchange for a reduction in taxes and control of biodiversity for the benefit of their biotechnology (p. 30).

The confrontation between the Bolivian government and NGOs rose to a new pitch on May 20 2015 when president Evo Morales issued Decree #2366, which opens natural protected areas to mining and oil extraction. And on June 18, Morales threatened to expel from the country any NGO or foundation that interferes with natural resource exploitation.

In August, García-Linera specifically singled out four private non-profit organizations, Tierra Foundation, Milenio, CEDIB and CEDLA, accusing them of serving foreign interests and manufacturing controversy among the country’s population, and warning them that if they did not quit their “political work” they can be closed down by the government. In early September the government declared that 38 NGOs, including CEDIB, were operating in the country “irregularly”, a statement that can be a prelude to shutting them down.

President Morales’s government has already carried out this threat to close down NGOs. In 2013 he expelled from the national territory the Danish non-profit organization IBIS for alleged meddling in the country’s politics, causing division among indigenous communities, and for making “intolerable” criticisms.

We interviewed CEDIB (Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia) executive director Marco Antonio Gandarillas. “We generate critical knowledge and information for the defense of natural resources, we face urban problems, as well as current issues in the country and region”, says the organization in its web site. “We provide inputs with which to generate a better informed critical opinion, supporting a culture of defense of human rights through the right to information”.

Cover of a book on mining in Bolivia edited by CEDIB, freely available here.

How long has the government of Evo Morales been in a confrontation course with NGO’s?

Back at the time of the eighth and ninth marches for the TIPNIS (2012) there appears a rupture between part of the indigenous social movement and the government. García Linera then published two books, Oenegismo and Geopolítica de la Amazonía. In both he is tremendously hostile toward NGOs that work on environmental issues, human rights and that work with indigenous peoples. Then the government started its media lynching.

In March 2013 this hostility is translated into policies, with the approval of Law 351 on juridical personhood, which seeks to repressively control NGOs and civil society in general. This law, without stating so openly, overturns everything with regards to juridical persons. It constitutes a profound reform of the Civil code, which has been in effect in Bolivia for the last 40 years. From here on, any collective person, association or NGO must be legally recognized by the state if it wants to exist in the country. There shall not be associations functioning autonomously from the state—the state will not consider them legal.

This law’s mechanism of control is the granting of juridical personhood. In order to obtain it, entities, associations and collective persons will need the government to approve their constituent elements, their internal statutes, in each and all of their terms. Our country’s public defender and United Nations’ experts have determined that this is unconstitutional as it violates universal rights of association.

Among this law’s excesses is the requirement that NGOs be aligned, in their work, action, goals and objectives, with national policies. The law mandates that the alignment must be very specific. This has been stated publicly by the ministers of planning and autonomy. This radically changes the functioning of NGOs. From being non-governmental they will now have to be para-governmental; that is, exist for the state, for the government.

Is this the first time the Bolivian state tried to co-opt NGOs?

We’ve seen (state) attempts at co-opting NGOs throughout our history. Between 2003 and 2004 president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada sent Congress an NGO bill that tried to control them, but there was very strong social rejection. Back then there were important NGO networks with much strength, which were able to resist, and the bill went nowhere. In the early 1990s president Jaime Paz Zamora established an NGO registry. But this did not turn out to be an effective control mechanism, because civil society and NGOs were very strong.

What has changed since then? Has Bolivian civil society been weakened?

The difference is that nowadays there is a huge and noticeable weakness and fragmentation among NGOs and in civil society. These government measures have generated much fear because they are accompanied by other, non-legal, means of intimidation. One any given day a powerful government bureaucrat can walk into your offices and, without granting the right to appeal, impose fines and offer few chances for paying in instalments.

This has put many an NGO in a situation of vulnerability. It generates a situation of public insecurity linked to the general insecurity with respect to government actions in other sectors. The government of Evo Morales controls all the powers of the state. There is nothing to guarantee even minimal rights to anyone.

Do you believe this trend toward authoritarianism is related to the government’s adoption of an extractivist economic model?

With regards to extractivism, the moment of rupture was during the start of Evo’s second presidential term. The government then makes a definite wager in favor of deepening the model of natural resource exports. Currently over 90 percent of Bolivia’s exports are natural gas, minerals and soy. For the government, that’s the way to go. The model is the export of natural resources and have the state receive the rent from these exports.

Here we see a deep divide between the international discourse of defense of nature and Mother Earth, and the concrete policies that put the environment at great risk in very fragile zones such as the Amazon, where oil exploration is beginning. Protected areas stop being protected areas to become petroleum zones.

García-Linera claims that the funding of CEDIB—and of the three other singled out organizations—comes from imperialist governments and transnational corporations. How do you respond to that charge?

None of our funding organizations can be accused of being right-wing or of supporting transnational corporations. They are solidarity organizations as old as CEDIB, with a long trajectory of human rights work. Some of them are linked to progressive churches.

CEDIB also gets funding on its own. We get money from the information services we provide; the state itself is one of our users. In fact, part of our research is independent because by having financial independence and funds of our own, we choose our research guidelines.

Do these four organizations really deserve to be bundled up in the same category? Or are they very different from each other?

Bolivian NGOs are very diverse. In any case, CEDIB is really not an NGO. It is a non-profit civil association. NGO is a pretty new term. CEDIB is older than those new terminologies.

García Linera lumps these four organizations together because our research work is socially relevant from any viewpoint. So far this year, CEDIB, CEDLA, Milenio, and Tierra probably also, have been mentioned as reliable sources in studies in and out of the country. We present the country’s economic, political and environmental situation in a nuanced way, things the government does not want to show or debate.

The government groups us together, these four organizations that are very different from each other. I am not aware of any proof that Milenio and Tierra are organizations of Gonzalo Sánchez de Losada, as García Linera has alleged. Even if they were, these organizations have the right to freely express their ideas. Even if they have ideas that are not shared by CEDIB, they have the same right to express them.

* Carmelo Ruiz Marrero is a Puerto Rican author and journalist. He is founder and director of the Latin American Energy and Environment Monitor. His blog on journalism and current affairs is updated daily. Ruiz is also a senior fellow of the Environmental Leadership Program and a research associate of the Institute for Social Ecology. He currently lives in Ecuador. His Twitter ID is @carmeloruiz.

This article was first published in Spanish in América Latina en Movimiento.

One Comment