by Yanis Rihi

Decolonising the transition: the unease

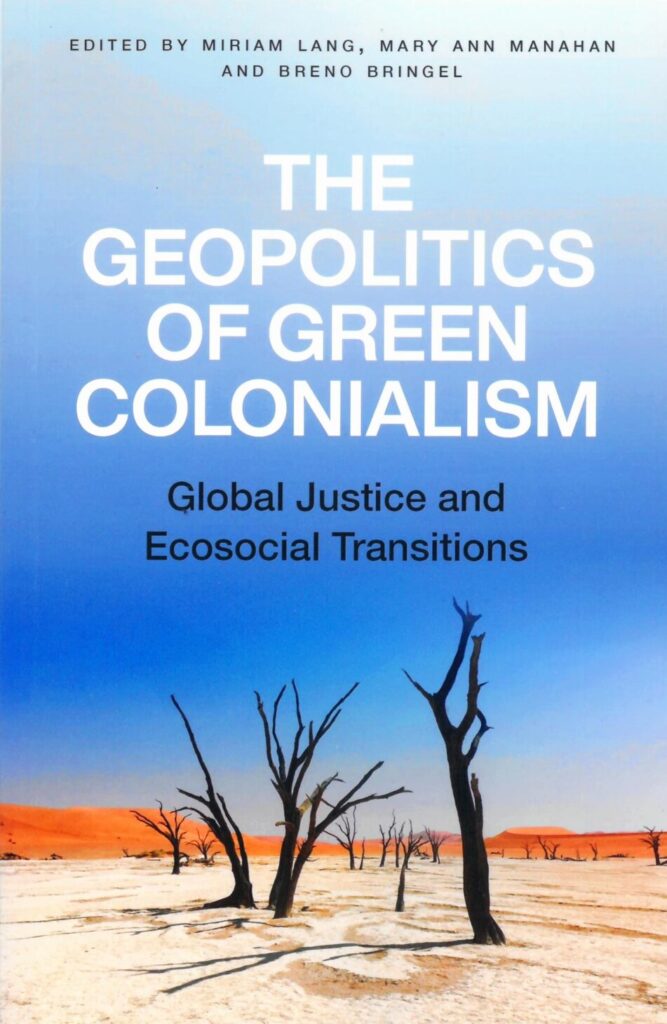

There is currently unease at the heart of the transition we are being promised. The energy transition, as a concept with a normative dimension, aims to transform energy systems into an energy mix composed of a greater proportion of renewable energy sources. Yet, an often-overlooked question looms in the background: In the name of decarbonization, who pays, who decides, and who benefits? This is precisely the debate that The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism: Global Justice and Ecosocial Transitions, a collective work in open access edited by Breno Bringel, Miriam Lang and Mary Ann Manahan, wishes to bring to the table.

Its contributors, from different socio-geographical and disciplinary backgrounds, name an unspoken truth: the planning of the transition perpetuates (neo)colonial relationships, both material and epistemic, that primarily weigh on the territories and communities of the Global South. Under the guise of urgency, climate action, when linked to market instruments, is not concerned with sustaining ecosystems but with accumulating capital and assumes, as a given, the existence in the Global South of zones dedicated to serving the needs of others, primarily in the Global North.

The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism: Global Justice and Ecosocial Transitions, a collective work in open access edited by Breno Bringel, Miriam Lang and Mary Ann Manahan.

The Decarbonisation Consensus as the only narrative

In the Introduction, the editors identify the “Decarbonisation Consensus” as the starting point for this dominant narrative, i.e., a global injunction to transform energy systems around renewables, electrify uses, digitise economies, and bet on so-called green growth. However, this bet is not without consequences for the multiplicity of realities in the Global South, as it is fundamentally based on asymmetrical access to resources, land, water, and minerals, and therefore on the Global North’s ability to externalise the socio-ecological costs of its transition onto the South.

Feffer & Lander (Chapter 4) show that Green Deals (in the United States, the European Union, and China) not only fall short of their promises but also displace their carbon footprint to the Global South. Their logic is not substituting energy sources, but rather accumulation. For the authors, the elephant in the room is the excessive overconsumption of Northern lifestyles, an underlying driver of climate change, revealing an apparent contradiction: the desire to add solar and wind power to the energy mix without necessarily phasing out fossil fuels, with the sole aim of maintaining an energy-intensive way of life.

However, producing these renewable energies necessitates massive infrastructure that requires copper, aluminium, rare earths, balsa wood, lithium, cobalt, nickel, and vast territories, all of which come mainly from the Global South, as well as the peripheries of the Global North, spaces that are economically and politically marginalised. Accordingly, it is no longer the time to evaluate trajectories solely based on their “domestic” CO₂ emissions. They must now be measured according to three glaring discrepancies: (1) the gap between national pledges and trajectories that are genuinely compatible with +1.5°C; (2) the gap between announced policies and effective implementation; and more importantly (3) the net impact on communities and environments in the Global South, including material footprint and imported emissions (Feffer & Lander, Chapter 4, p.72–73).

Imaginaries that dispossess: terra nullius and empty spaces

This decarbonisation consensus is therefore not neutral; its ramifications are profound and tinged with what might be called “green colonialism”, mobilising “both neocolonial ecological practices and imaginaries. Under a new twist on the rhetoric of ‘sustainability’, a new phase of environmental dispossession of the Global South is opening up…” (Lang, Bringel & Manahan, Introduction, p. 3)

Indeed, in addition to infrastructure and markets, this agenda is also taking shape through imaginaries, such as the fiction of terra nullius, to refer to territories in the Global South that are supposedly “empty spaces” available to host wind, mega-solar, hydrogen projects, or green mineral mines. As Lang, Bringel and Manahan explain, the colonial notion of “empty spaces” has been repurposed today to legitimise territorial expansion for green energy investments. However, to say that a territory is “empty” is to erase its history, uses, knowledge, rights, and the ecological links that compose and nourish it – as well as the peoples who inhabit, shape, and depend on it.

Green hydrogen: the new frontier of green colonialism?

Dietz (chapter 1) highlights how the green hydrogen sector, i.e. the production of hydrogen from supposedly carbon-free sources, depending on the supply chain of renewable electricity and the overall efficiency of the process, is becoming one of the most visible frontiers of this neo-colonial dynamic, to which leaders in the Global South seem to be fully committed. For instance, Germany is forming hydrogen partnerships with several countries, including Morocco, South Africa, Namibia, Chile, and soon Brazil, Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico. Many of these countries are also participating in multilateral initiatives, such as the Clean Hydrogen Mission, which is co-led by nations including Australia, the European Union, and the United States. This collaboration is already shaping a market and establishing value chains, in which access to resources and space in the Global South becomes a technical and financial necessity for the Global North’s energy transition.

However, this enthusiasm ignores the economies of scale that are supposed to accompany the development of this sector. The development of gigantic wind and solar farms is set to take root in territories already at the scene of conflicts over land use, water, grazing, and fishing rights. These additional demands amplify socio-ecological tensions and injustices in the name of a “win-win” narrative that looks attractive on paper. Ultimately, the current transition is less of a break than a shift without overhaul; the energy flows are changing colour, but not the power relations: “…a mere switch of the energy source while maintaining the existing authoritarian political dynamics and… hierarchies of the international order.” (Hamouchene, Chapter 3, p. 59). This is what field research shows: the costs are inevitably paid somewhere, because decarbonisation here means reterritorialising infrastructure elsewhere. As Lang, Bringel & Manahan (Introduction, p. 4) remind us, “… all the ‘critical raw minerals’ and land extensions needed… will come from somewhere”.

Illustration by Othman Selmi. Originally published by the Transnational Institute in the essay “Resisting the new green colonialism by Saber Ammar (25 October 2024). Republished with artist’s permission.

From somewhere, where the transition is paid for

This is where the book challenges us, reminding us of the systematic invisibility of the Global South in the determination of these agendas in international arenas. These agendas require reclassifying the “somewhere”, from where resources come, as “empty spaces”. Yet this “somewhere” has names, waters, soils, species, struggles and hopes. In Ecuador, deforestation is rampant due to Chinese demand for balsa wood, a lightweight material used in wind turbine blades (Yanez & Moreno, Chapter 5). In South Africa, the development of hydrogen infrastructure overlaps with artisanal fisheries and local agriculture. In South America’s “lithium triangle,” pumping alters fragile hydrosystems, pitting mines and indigenous communities against each other over the most precious resource: water (Svampa, Chapter 2).

Hamouchene (Chapter 3) gives a precise account of this invisibility in Morocco, where solar energy reveals the socio-ecological downside of our transitions. In Ouarzazate, a solar power plant has been built on 3,000 hectares of Indigenous Amazigh agro-pastoral land without consent, a “green grab”, financed by approximately USD 9 billion in multilateral debt backed by public guarantees (socialisation of losses). The site also requires high water consumption in a semi-arid area. Likewise, in Noor Midelt, 4,141 hectares of collective land and forests have been expropriated from local populations to serve the public interest.

When transitions are written on credit

Added to this geography of costs is their financial engineering. “Debt comes into play to reinforce asymmetries…”, note Lang, Acosta & Martínez (Chapter 7, p. 106). Debt, then, is what organises this international division of labour and nature and “must be understood as a powerful tool of domination” (Ibid.). Its strength lies in a well-oiled moral narrative of “incapacity” and “individual responsibility”, which locates the debt responsibility in the Global South. Even the recent Loss and Damage Fund, established as part of the international climate agreements supposedly as a social justice measure to support countries in the Global South with the climate crisis, is evolving towards loans – and hence towards new debt. This is part of the dominant logic of “climate finance,” which several authors have already described as being part of a colonial international financial architecture.

With this in mind, the book advocates for the dissemination of a vocabulary and practices of restitution and reparation, as well as for the fiscal and territorial sovereignty of countries in the Global South, in combating global warming and determining their own transition paths – a prerequisite for genuine global justice. Not addressing these issues is a recipe for a transition financed by credit, which would only repeat the historical patterns of domination between the Global North and South.

An old story that repeats itself

The strength of the concept of “green colonialism”, which lies at the heart of the book’s argument, is that it precisely identifies this historical continuity. The idea should be understood less as a new contemporary trend than as a socio-political process rooted in the long history of colonial powers and capitalist expansion. “Green colonialism was thus historically forged with capitalism and the commodification of Nature… expressed in the ‘coloniality of Nature’.” (Lang, Bringel & Manahan, Introduction, p. 9). In this interpretation, “Nature” is not just a biophysical stock, it is an object that has been systematically seized, carved up and recomposed by regimes of accumulation that assign certain regions of the world, mainly “subaltern spaces” in the Global South, to be exploited, destroyed and reconfigured according to the needs of the moment (Svampa, Chapter 2).

In this regard, Dorninger (Chapter 6, p. 91–102) reminds us that what might be called “imperial appropriation”, which characterised past centuries, is now evolving into more discreet forms, “camouflaged under free trade and market price rules.”, naturalising the power relations that organise the material outsourcing (resources, land, labour) to the Global South. In this respect, his analysis complements the book’s argument that sustainability or carbon neutrality does not abolish the structure of unequal international ecological and commercial exchange, a point empirically supported in the literature. On the contrary, it reshapes it through new inputs (minerals, land, water) and new infrastructure, as is currently the case with the transition to low-carbon economies.

Charity that disarms resistance

This long history of asymmetrical North–South relations produces a persistent tension between conservation and destruction, which, today, are mutating, becoming hyper-equipped, through datafication and territorial control, and socially legitimised around the promise of decarbonisation and a “green” transition. This, in turn, helps justify the transformation of specific spaces into “sacrifice zones”, an inevitable consequence, and it is precisely what complicates forms of resistance, “by proclaiming itself environmentally friendly and indispensable in order to grant humanity a future…” (Lang, Bringel & Manahan, Introduction, p. 5). After all, who would want to oppose something that claims to save humanity? The moral framework seems locked in advance – which is precisely where it must be pried open.

Illustration by Othman Selmi. Originally published by the Transnational Institute in the “Dismantling Green Colonialism” dossier (16 November 2023). Republished with artist’s permission.

Beyond the North–South dichotomy

The book argues that we are at a turning point regarding climate and contemporary colonial reconfigurations. Hence, there is an urgency, and perhaps even a duty, to go beyond criticism and map out alternatives, understand the conditions that amplify them, and learn how to build bridges between them. Indeed, many options already exist, as evidenced by local and regional struggles for environmental and climate justice, grassroots community-led experiences in just transitions, degrowth ideas and initiatives, multiple forms of resilience, and a range of transition policies that deviate, to varying degrees, from the dominant approach. However, these alternatives, according to the book, suffer from a standard scale bias: they often speak the language of the local, when they should also be placed within a global justice perspective, capable of linking frameworks for action to multiple worldviews. As Reyes (Chapter 17, p. 215) notes, addressing this scale bias requires articulating local initiatives with broader emancipatory struggles, “combining visions and struggles with environmentalism, feminism, internationalism or cooperativism, requiring a holistic perspective and action.”

The book explicitly frames this as a core premise: ecosocial transformation requires planned degrowth in the Global North, alongside a convergence of critical voices across regions. From this perspective, moving beyond the North–South dichotomy does not mean denying colonial asymmetries; instead, it calls for the formation of trans-regional alliances against green colonialism. On the one hand, many current conflicts in the Global South are rooted in forms of “internal green colonialism”, where partnerships between domestic elites and global capital facilitate extractivism and green land grabbing, particularly in Africa (Bassey, Chapter 9). On the other hand, the Global North is not a homogeneous space; it also contains critical voices and grassroots initiatives that deserve to be amplified and connected to transformative proposals emerging from the South. In this respect, the entire third part of the book is devoted to highlighting a plurality of degrowth movements in both regions.

This analytical shift also invites us to reconsider countries that do not fit neatly into the North–South binary. The special case of China is worth noting here, as Feffer & Lander (Chapter 4) rightly point out. It is the most significant greenhouse gas emitter in total volume (though 4th per capita), the world leader in renewable capacity, and still largely dependent on coal, the most polluting fossil fuel. This ambivalence confirms that the key dividing line is not automatically between North and South, but somewhat between different material (production and consumption) and political regimes.

Alternative paths

In this context, a decisive task remains, both epistemic and political, that of documenting, connecting, and consolidating the “multitude of experiences” that are already making ecosocial transitions credible alternatives to green colonialism. These “processes of re-existence” are “linked to community energy, agroecological projects, urban gardens, and alternative economies.”(Lang, Bringel & Manahan, Introduction, p. 12).

For instance, Nnimmo Bassey (Chapter 9) points out that there is not “one” Africa, but multiple contexts, which are essential for localised transitions. He documents the rise of popular movements defending land, water, and seas, and achieving concrete victories, from the Ogoni people of the Niger Delta, who have historically stood up to Shell, to other coalitions for environmental justice, food sovereignty, and the protection of the commons. Consequently, the author calls for these forces to be united around a shared political compass, for African unity by the people, a kind of “pan-African movement”, rather than one driven by geopolitical injunctions from above. Similarly, Roa Avendaño & Bertinat (Chapter 12) propose making communities the active subjects of the future system. For their part, the central question thus becomes: how, in concrete terms, is community energy built? As they show, the answers involve connecting a variety of dimensions, including culture, governance, the democratisation of energy, territorial control, and the co-construction of an energy commons policy.

Zo Randriamaro (Chapter 13) illustrates this ambition through African ecofeminisms, which articulate gender, class, race/ethnicity and coloniality to deconstruct modes of domination and propose lived alternatives. In many territories, rural women and indigenous peoples defend their land, autonomy, community ties, and interdependence with living things – not as a matter of principle, but because, most of the time, their survival depends on it. These practices – such as care, collective management, sufficiency practices – already constitute a daily policy that destabilises extractivism and opens up just and habitable futures from which we should draw inspiration.

A visit to the Cauca Valley in Colombia illustrates this well: just, pluriverse, and counter-hegemonic transitions are already underway, even if they remain fragmented (Campo and Escobar, Chapter 16). They do not start from an abstract design, but from relational worldviews that reaffirm the interdependence of living beings and reconnect the links between decarbonisation, food sovereignty, post-extractivism and plural justice. In sum, truly transformative ecosocial transitions are less a question of inventing solutions than of rehabilitating ways of living and caring that the dominant developmentalist logics have historically marginalised, learning tactics of resistance and re-existence, and looking at territories from the perspective of those who weave them together.

Global Justice Now’s campaign briefing “Resisting green colonialism for a just transition: Trade and the scramble for critical minerals” further documents impacts of critical minerals mining, and focuses on dismantling unjust trade rules.

From local to translocal: towards eco-territorial internationalism

If these experiences are to have an impact beyond the local level, they require transnational structures to connect them. This is the proposal of what Bringel & Fernandes (Chapter 17) call “eco-territorial internationalism”: a practice of interconnecting struggles and alternatives which thereby acquire a “global sense of place” without necessarily dissolving into global abstraction. In that sense, “This internationalism needs to critique global asymmetries and take an anti-imperialist stance, challenging the ties between the international division of labour, green colonialism and ecological imperialism in its thirst for resources and the continuous generation of sacrifice zones.” (p. 240)

This horizon is already taking shape: initiatives such as the Climate Justice Alliance – a multi-territorial platform in the United States – the Eco-Social and Intercultural Pact of the South – a group of individuals and organisations from different Latin American countries – and the Global Tapestry of Alternatives – a network of networks linking grassroots groups, social movements and organisations – are building bridges between local initiatives, sharing methods and safeguards, synchronise campaigns and actions, and identify common obstacles to overcome (green capitalism, extractivism, credit finance). The aim is not so much standardisation as the circulation of operational concepts, legal tools and formats for action, as well as the creation of solidarities and collaborations for joint actions, to scale up what works and abandon what is not sustainable.

Conclusion: decarbonising without global justice means perpetuating injustices

Ultimately, the thesis presented in the book is straightforward: changing energy sources without altering the system that governs them entails shifting costs in space and time, as well as reinforcing historical relations of domination. The book successfully highlights the material and epistemic workings of green colonialism, analyses the geopolitical interconnections that support it, and then opens up a space for alternative strategies by cataloguing practices and knowledge that already exist but are systematically fragmented and rendered invisible. As announced at the beginning of the book, it aims to reveal, analyse, and mark out paths towards a “dignified future”. On this front, it delivers convincingly.

It also reminds us of what should be obvious but is often overlooked by the dominant climate rhetoric: the fact that decarbonization will not occur in a vacuum, but will take place in specific territories rich in heritage, debts, dependencies, living environments, and social classes. In that sense, “decolonising the transition” is not just simply a slogan; it is a daily practice of justice that requires a redistribution of the powers to decide, to inhabit, to extract (or not to extract), to produce, to circulate, and to rewrite our imaginaries of prosperity. As shown throughout the book, there are already intellectual, political, and practical alternatives. The current challenge is to make them visible, connect them, and give them a foothold in public action.

It is now time to connect these archipelagos of initiatives into a translocal force, an actual “movement of movements”, capable of aligning, from the local to the global, commons, reparations and just governance to offer truly emancipatory post-carbon trajectories. The question is not to slow down the ongoing transformation, which is fundamentally necessary, but rather to reorient it, always guided by the underlying question: how, with whom and for whose benefit?