The local communities struggling against extractive projects in the Ecuadorian Amazon are faced with a tough choice: uplifting their condition with the corporation’s money but selling out their land, or fighting to keep their ecosystem healthy, despite poverty and destitution. A reportage from the ground.

“As a farmer, it’s hard to fight against a big company like Gran Tierra Energy. Nobody will be picking cacao for you while you are protesting, nobody will feed your cows while you are meeting the lawyers to sue the company!” says Doña Melva, a farmer from the region of General Farfan, on the Ecuadorian border with Colombia.

Like most of the inhabitants of this Amazonian region, she makes a living out of cacao and corn plantations. Clean water pipes do not exist here, and people rely on the small tributaries of the Rio San Miguel to address their water needs. “But when you know that a foreign company is threatening your only clean water sources, you don’t think twice before taking part in the resistance.”

In General Farfan farmers began uniting against the oil exploitation project of the Canadian company Gran Tierra Energy in 2020, when Don Harry, president of Imbabura, a small farmers community, started alerting his co-villagers about the incoming danger. By reading an extract of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) provided by the company during a socialization event, Don Harry spotted some fallacies in the document. Therefore, he contacted UDAPT (Unión de Afectados por Texaco), a local NGO providing support to communities opposing oil and gas companies, and he asked for help for a thorough analysis of the EIA.

What came out was frightening. Several villages, as well as rivers, were not appearing in the EIA, the number of families present in the territory was much lower than in actuality, the impact of gas flares on humans was assessed as “not relevant”, and the number of gas flares was much higher than what was declared during the socialization meetings, for a total of 14 new gas flares.

“There is no doubt that this is all part of the company’s strategy to mask the real impacts of their project: less families means less responsibility and less compensation. This matters when it comes to presenting the study to the Ministry of the Environment to receive the necessary licenses” explains Jairo Salazar, lawyer of UDAPT.

Don Bacilio and Dona Melva chatting in their patio (credit: Francesco Torri).

Who is Gran Tierra Energy?

Gran Tierra Energy is a Canadian oil and gas company directed by CEO Gary S. Guidry with headquarters in Calgary and offices in Quito and Bogotá. Its main operative area is Colombia where its reputation among indigenous and farmer’s communities is of a highly unreliable company due to the unethical way it dealt with the oil spills in the Mocaoa and Caqueta rivers. Overall, Gran Tierra in Colombia runs 22 oil blocks impacting an area of more than 1.4 million hectares and has a total production of 33.100 barrels of oil per day.

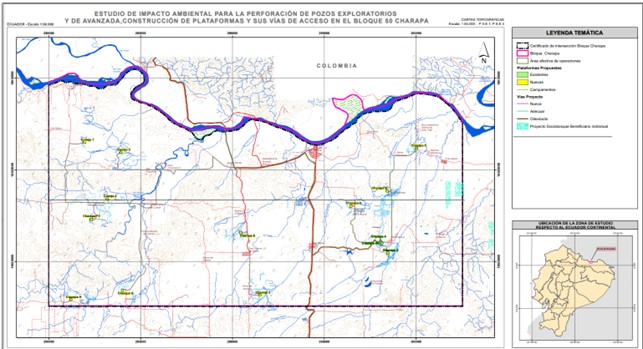

In May 2019, Gran Tierra Energy received its concession to operate the Blocks Charapa (50) and Chanangue (51), where over 600 farmers families live out of cacao plantations and small-scale livestock breeding. Such concession was part of the “Ronda Intracampos II”, a government plan to allocate not-yet-exploited areas existing between larger oil blocks.

In Ecuador, this type of policies are in line with the history of intensive resources exploitation that goes on since the 70’s, when the US giant Texaco started extracting oil and gas from the Amazonian provinces of Orellana and Sucumbios. Since then, despite the scandals of violence and environmental destruction reaching worldwide media resonance and local communities winning constitutional legal processes, things have changed little in how transnational companies operate.

Today, Ecuador is the fourth Latin American country in terms of oil reserves, following Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil, with an active production of almost 500.000 barrels per day: since the beginning of 2024 the Ecuadorian government earned around 3 million dollars. For this very reason companies like Gran Tierra Energy are still allowed to operate in the country without much concern about environmental or human rights standards and the climate crisis.

Quickly after signing the service delivery contract, under which the company guaranteed the government a 51% of the revenues, Gran Tierra started producing its Environmental Impact Assessment, a necessary step to obtain the Environmental Licenses from the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment.

The outcome was a social and environmental analysis full of fallacies and omissions, to which local farmers soon started opposing. Nevertheless, Gran Tierra obtained the license for the Chanangue Block in February 2022 and for the Charapa Block in March 2022.

Passages on the bridge dividing Ecuador and Colombia (credit: Francesco Torri).

Local Farmers say no to contamination!

“I can’t believe they obtained the licenses!” Claims Don Panchi, a local school teacher and activist, “in Chanangue they plan to build the drainage of Platform C right next to the Rio Benavides and Rio Dento, two rivers on which the life of 40 families depends on! In Charapa they will install a gas flare less than 400 meters from a school… a school that strategically does not appear in the EIA!”

Gas flares are a technology used to burn directly in the open air the gasses derived from oil extraction, which contain more than 250 highly carcinogenic toxins that could harm people living up to 60 miles from the flare and decrease crop yields.

Don Bacilio from the “Las Palmas” village explains to me that only 36 families have been consulted of the 600 living in the area of interest, and that the government, before granting the license, should have made sure that the consultation process was conducted in accordance with the law. He refers to the 169 ILO Convention, which requires all companies operating projects that may influence local communities to consult them in a free, prior and informed manner.

Ecuadorian farmer driving back home from his cocoa fields (credit: Francesco Torri).

“What Gran Tierra did instead was a mere socialization explaining in vague and misleading terms a project that was going to happen anyways, independently of our opinions” claims Don Bacilio. “This is why I started, together with Don Oscar and Don Santos, the Environmental Rights Defence Front (ERDF), a resistance group created with the objective of protecting farmers’ land from Gran Tierra’s operations and upholding their right to be consulted, to life, to water, and to live in a healthy environment, all recognised by the Ecuadorian constitution.”

The ERDF, supported by UDAPT lawyers, started organizing the resistance in General Farfan in 2021, by going from community to community to inform them about the risks of Gran Tierra’s project and to show the fallacies and omissions of the EIA. This allowed the movement to grow strong, counting dozens of members by 2022. Leaders like Dona Melva started organizing peaceful demonstrations and press conferences to amplify their voice nationally. In response, the company increased its pressure on individuals to obtain access to land and begin the seismic exploration phase, especially in the Charapa Block.

This phase is the first stage of the oil extraction process and allows the company to know exactly where hydrocarbons are. To obtain such data, 559 dynamite pots are detonated at variable depths in order to study seismic patterns, showing presence rather than lack of oil. These operations are particularly invasive, not only for the noise and the soil disruption, but also because they can dry up underground water sources, necessary for the survival of local communities.

“The company needs landowners’ consent in order to conduct the seismic exploration, because this process works only when dynamite explodes along the lines of a grid they track on the map” explains Don Harry “if one of us doesn’t consent access to her territory, the analysis can’t be done because the data are incomplete. For this reason, the company insists so much at this stage and offers money individually to farmers.” Such a divide and rule strategy is allowing Gran Tierra Energy to access the territory. As of April 22, 2024, the company’s men drilling holes and placing dynamite have been seen by Don Harry close to his property.

A map from the environmental impact assessment of Gran Tierra Energy

An unexpected plot twist

Nearby, in the Santa Marianita community, the resistance process came to an end after violent military repression on the 15th of September 2023.

On that day, the community decided to block the road to prevent the company’s vehicles from accessing the platform Charapa B and to uphold their right to resistance, enshrined by Article 98 of the Ecuadorian Constitution. However, the military and the police intervened in defense of the company Gran Tierra Energy and soon the situation escalated into violence, with several people injured. Soon after, the community signed an agreement with the company and nobody agreed to be interviewed.

As of today, the platform Charapa B is the only one active and productive. However, thanks to a successful negotiation process between the company and the community of Patria Nueva, soon also the platform Charapa 3 will be active, with a gas flare burning less than 400 meters from the village. Patria Nueva was part of the resistance movement until March 2024. Its leaders were among those leading the opposition to oil exploitation, as this community still suffers the damages left by Chevron in the 70’s. Crude oil pools surround the village and still overflow during heavy rains, as nobody ever cleaned them.

Then why did they negotiate with Gran Tierra Energy?

Documents on the Environmental Impact Assessment of the Charapa Block laying on Jairo Salazar’s desk, in the offices of UDAPT (credit: Francesco Torri).

Patria Nueva’s President Edison Angulo confessed to me that he was receiving pressure from too many sides. He thinks most local farmers were fooled by the promises of the company to reduce economic hardship and ameliorate access to basic services like health and clean water. “As a President I had to follow the will of the majority. I tried my best to show them that it doesn’t make sense to have a polished health center if they will get us sick through the gas flares… that they give us clean water while they pollute our rivers… but people can’t look forward… the company manipulates their minds to focus only on short term and personal benefits” says Edison.

He invited me to join the meeting with Gran Tierra Energy’s representatives, where the negotiated agreement was read out loud and people had the chance to sign for job opportunities. On the 17th of April, 2024, at noon, hundreds of people gathered under the covered football pitch. Most came from the fields, still wearing boots and dirty clothes. It was extremely hot but nevertheless some elders took advantage of the situation to grill some chickens and smoke up the place.

In the middle of the pitch sat the representatives of the company, community leaders, and two government authorities. After introducing the meeting, Don Edison started reading the agreement. It was overly complex and long, but in sum what the communities obtained was: a schoolroom equipped with computers, new roofs for all houses, a water tower to capture rainwater, a water well with a pump, workplaces, economic incentives for farming projects and an actualization of the census.

Doña Melva, Don Bacilio, Don Harry and Don Edison, as many other farmers, have given tears, toil and sweat to keep their lands free from contamination, but the powerful means and strategies of the company managed to defeat them. The losses their communities will suffer in terms of health and biodiversity are undeniable, nevertheless four years of strenuous fight have not been useless: none of the negotiated agreements would have existed without resistance.

Gran Tierra Energy’s representatives meeting local residents in the village of Patria Nueva (credit: Francesco Torri).

It is inevitable that in a state of necessity as the one lived by the communities of General Farfan, where the government is absent, it’s hard for a family to refuse a better school for their kids or a better health center to receive medical assistance. This apparently absent government is the same government that is now giving environmental licenses to a project with drastic environmental consequences and that refuses to enforce any communities’ consultation mechanism. Such an institutional and political scenario holds a high degree of liability, or better said complicity, in the oppression and exploitation exercised by companies like Gran Tierra Energy towards local communities.

Francesco Torri is an investigative journalist trained in environmental law, currently reporting on socio-environmental conflicts linked to the misconducts of multinational companies. You can follow him on Instagram @resistance_voices.

This story was produced with support from the Earth Journalism Network.