by Dylan M. Harris

The best stories about climate change are not about climate change. Rather, they are about small, particular, mundane events. They are personal and intimate. And they are grounded in specific locales. These ‘small’ stories show different ways of imagining, creating, and sustaining meaning in the face of climate change. As the climate changes, it is important to pay attention, to listen, and to tell small stories so that they can tell more small stories.

A simulation of stratocumulus clouds in a 3-by-3-kilometer patch of sky, as seen from below. New computer simulations suggest that as the Earth becomes warmer, clouds will become scarcer, in turn fostering more global warming. Source: Kyle Pressel

In a recent article, Meehan Crist asks, “Why is the story of climate catastrophe so hard to tell?” There any many possible answers to the question, but maybe climate change, or at least the way it is often portrayed, is too big: it is often perceived as happening over ‘there’, to someone else. However, it is also intimately happening to me. It’s disappearing clouds and my cup of coffee. It is equal parts atmospheric and personal, distant and immediate. It is sometimes uncanny, but it is not unknowable. In a world made non-sensical by rapid climate change, perhaps stories, one of the oldest forms of human meaning-making, can help make sense of the changed and changing world.

But, where do these stories come from? Stories aren’t new, but they are currently in vogue. Google does storytelling. Climate scientists do storytelling. Yet, there is hardly any consensus about what ‘counts’ as a story. Or, more importantly, who gets to tell stories and who listens. The stories society values (at least some of them), as evidenced by mainstream year-end lists, do not reflect an ability to think collectively. For the past few decades, the stories on these lists have focused on the individual, while, at the same time, climate research has pointed towards the deeply interwoven nature of the earth system. Each sphere–the atmosphere, the biosphere, the cryosphere, etc.–is interconnected through complex systems of inputs and outputs, fluxes and exchanges. Yet, the stories society-at-large values do not necessarily reflect these interconnections.

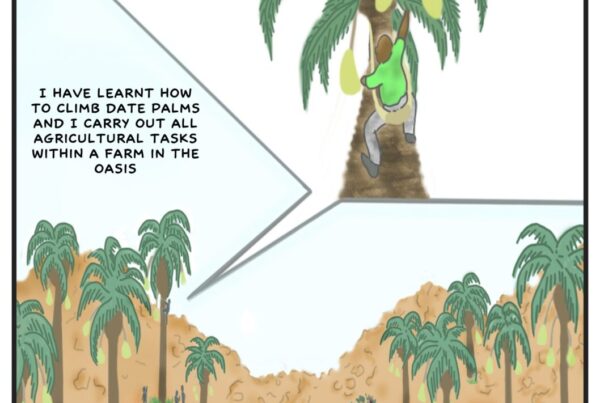

Stories inspire other stories. Loud stories inspire loud stories: stories of calamity, and catastrophe. And in all of these stories, there is often a ‘we’ that survives the end of the world, and they can keep telling their stories about big, loud futures. There is immense power in the way the future is imagined. If, for many who are not directly impacted, climate change is difficult to perceive, let alone address, because it is too big, perhaps it is time to tell small stories. Or, better yet, it is important to listen for small stories, those that pay closer attention to the ways climate change manifests in the quotidian experiences of day-to-day life. These stories may help dismantle the bigness that blurs the changing climate. By listening and telling stories from the perspective of the rest of ‘us’, those that are not a part of the big ‘we’, it may be possible to begin reconsidering the apocalyptic imaginaries so-often associated with climate change. I argue there’s justice in reconsideration.

Coffee with cream. Rising temperatures and intensifying droughts are expected to affect coffee production and prices. Source: Gifer.com

What does it mean to tell small climate stories? How can these stories reflect the interconnectedness of the earth system, how even the smallest molecule moves from the bottom of the ocean, to a hurricane, to my lungs? To only begin answering these questions, I want to suggest a working manifesto for telling small climate stories.

In an article that stitches together smaller stories within geography, Hayden Lorimer provides a few helpful ways of considering small stories. I have adapted three main points from his article to the project of telling small climate stories and will discuss each in turn:

i) Small climate stories should focus on the particular and the mundane: Rather than the catastrophic stories associated with climate change, small stories should focus on the relatively normal and clearly-happening but hardly-noticeable. By focusing on the particular and the ordinary, climate change becomes more knowable. It can be seen, smelled, heard, tasted, and felt. Instead of seeing climate change happening to others –polar bears scrambling across melting Arctic sea ice or islands (and the homes on these islands) disappearing due to sea-level rise– it becomes personal. Climate change is the sun on my face during an unseasonably warm day in January. It’s the feeling of lake grass, flourishing in warmer temperatures, tickling my stomach when I go for an early fall swim. It is here, not there. It is mundane, meaningful, and manageable without being extraordinary and overwhelming. It is still serious and dire, but it isn’t disarming. And, while this understanding of the climate may be personal, it becomes something shareable and relatable. Small stories tell other small stories, and the particular and mundane travel to other locatable climates and contexts. The smaller parts of big climate stories – understanding how vulnerable populations are always the most impacted by climate disasters, for example – become more knowable. It is critical to keep in mind that life persists amidst catastrophe, even if (some of) our imaginations are conditioned to think otherwise. As small stories travel, the larger climate story shifts.

Comet Pond, home to the many late-fall swims and flourishing lake grass mentioned above. Source: Author.

ii) Small climate stories tell of large-scale conceptual shifts on personal and intimate terms: Paleoclimate records–slices of past climates taken from ice cores and ancient mud sediments– indicate a volatile planet. Yet human life persists, balanced precariously between geologic processes that provide the necessary (and incredibly small) window of temperature that allows human life to thrive. But, as carbon accumulates in the atmosphere, the planet warms at rates previously unseen in the climate record. While there is much known about climate change, it continues to change, shifting more and more towards the unknown, towards what some have termed ‘global weirding.’ It is necessary to understand why the worldwide climate is shifting. It is important to understand the relationship between the warming Arctic and the weakening of the North American jets stream. However, it is also important to acknowledge that these large-scale shifts can be felt and known. Small climate stories center on the personal and intimate, making the embodied experience of the atmosphere a site of climate knowledge production. Our bodies, perched precariously as interlocutors of the earth system, tell us about the climate, and our bodies tell stories if we listen. My pelvis –which I broke when I was 13 years old while building a homemade zipline in my backyard– still aches when a storm is rolling in. My skull responds to changes in barometric pressure, sometimes giving me headaches. It’s like a superpower I never really asked for. As the climate continues to change, it is important to listen to our bodies; they tell small stories, too.

iii) Small climate stories should be treated as entry points for understanding abstract climate change in local contexts: The largest and loudest climate story is that it is happening now, it is all our fault, it requires societies to respond quickly and boldly, and there are really only a few ways to deal with it. Glaciers are melting, sea level is rising. Species are going extinct. We are all to blame. The world –all of it– must come together to create large-scale solutions, to tell bigger and louder stories about big and loud futures. Small climate stories challenge the largest and loudest story. Small climate stories show exactly where, how, when, and by whom the climate is changing. These stories tell other stories that begin to chip away at the notion that climate change is exactly one thing caused by an entire people. Climate change becomes less abstract and more locatable, and, as such, more relatable and doable. The largest and loudest climate story makes climate change too big, but small stories travel, connecting specific points in time and space to others through personal, knowable, meaningful experiences. The trees near my home in Massachusetts are unsure of when to bloom. When I talk to my father, the trees near my childhood home –nearly 2100 kilometers south, in Mississippi– are also unsure. Their precarity is separate but shared. Most importantly, there is no one climate story told by an entire ‘we’. Rather, there are multiple smaller stories, interconnected and told from the perspective of the rest of ‘us’.

My Dad, talking about the low water levels in the creek near where I grew up in Chunky, Mississippi. Source: Author.

The best stories about climate change are not about climate change. Rather, they are about small, quiet events that take place in the climate –the container (full of the weather, geology, birds, and bugs) that holds and make possible meaningful human action. They show different ways of imagining, creating, and sustaining meaning in the face of climate change. As the climate changes, it is important to pay attention, to listen, and to tell small stories so that they can tell more small stories.

Dylan M. Harris is a PhD Candidate in the Graduate School of Geography at Clark University. There, he studies the stories we tell (and don’t tell) about climate change and is interested in the role stories can play in helping us better understand and address climate injustices.

Reblogged this on POLLEN.

This is lovely. Thanks.

It’s funny isn’t it, the terms that are handed down to us to use – “climate change”, “the environment”. Such weird terms to use when talking about the earth on which we depend. Kind of like a young kid referring not to Mum or Dad but to “the parent”.

Not surprising with that heritage of separation that we struggle to remove it from abstraction to concrete everydayness. I guess that’s one of the silver linings of living at the end of one age and the beginning of the other – we get to witness our own homecoming. Trippy 🙂