I am not closer to Giulio if I am Italian, Marxist, or studying unions. I can be Giulio tomorrow just because I am a researcher.

Last week Giulio Regeni, a colleague and fellow researcher on fieldwork in Egypt was tortured to death for days. His body was discovered on Wednesday 3 February 2016, dumped on the side of a road in Cairo. Giulio was doing his PhD at the University of Cambridge, and was looking at the formation of independent trade unions in post-Mubarak Egypt. A highly contentious topic in the country, his contributions from Cairo were published in the Italian newspaper Il Manifesto under a pseudonym. His last report, published posthumously under his real name, can be found here.

Giulio Regeni’s work was no doubt going to be an important contribution to his field; he was an up-and-coming scholar of the region. This piece is an attempt to bring together some of the voices of indignation that have been raised in the past days in different amademic email lists, calling for solidarization, protest and action within the international academic community, to recognize the value of academic work, and to safeguard academic freedom.

Source: bbc.co.uk.

“As a researcher that has herself been in the Middle East and not always in the safest situations for study/research I feel that this tragic event cannot, and should not, be left ‘unattended’ and not addressed ‘critically’ (whatever being critical means). I happily signed the petition promoted by Giulio’s supervisors. I thank them for that draft and for taking some steps towards justice for Giulio and all those who have been abducted, tortured or even killed because they are part of some opposition groups in Egypt.

But this is not only about Egypt and Al Sisi’s dictatorship, and this is not only about a white man going to do international research.

What I feel, is magisterially expressed by Neil Pyper here, where he talks about Giulio and the attack to academic freedom. My question is, what does it mean to be free? What does it mean to be critical at this point? As Pyper puts it, what happened has much broader implications for higher education and research both within and beyond the UK. My question pivots around the role of research and our institutions. Can the researcher be safe and critical? In order to think and act critically, are there mechanisms that we can put in place to safeguard academic freedom without risking lives? How can we protect ourselves? And how should we be protected?” (D. M.)

Giulio was a brilliant and promising scholar, interested in the informal economy and the workers movements, he was a Gramscian. He should be a symbol for all critical geographers across the world. (U. R.)

The following letter, addressed to Giulio’s friends and advisors, was written by a fellow PhD candidate at Yale University. We re-publish it here with her permission:

“Dear Friends of Giulio,

Giulio was one of us. What happened to him can happen to any of us doing research, to any of the students we meet and advise every day. His horrific death needs to shake up the academic community!

Reacting to Giulio’s cruel homicide honors him, and goes beyond him. It reasserts what is the role of the researcher, what it means to do research.

We need a bigger protest to express our indignation.

Tell us who was Giulio. Why he was killed. Put together a short essay about him, a video on youtube and the like. Give us data, help us to realize that he was one of us, that we can be him.

Then, coordinate action: Ask us to flood emails to our Egyptian Embassies, or to the Guardian, or whomsoever it takes. Ask us to send images of silent students sitting in protest. Each department, at least, in the Humanities and the Soc Sciences, since we have a similar modality of doing research. PolSciences, Anthro, Geography, cultural studies, Middle Eastern, History, etc..

If the death of Giulio speaks of who the Egyptian authorities are right now, how we react to it speaks of who we are, right now, as an academic community, what is our professional collective identity, what is our role in the world we live in.

Please do not read this as condescending, or polemic. I feel we should not miss this opportunity, and you have it right there in your hands. You knew Giulio, and you can lead us to know him, and, in return, to stand up for ourselves.” (L. C.)

I am not closer to Giulio if I am Italian, Marxist, or studying unions. I can be Giulio tomorrow just because I am a researcher.

“I have written an open letter to Giulio’s friends and advisors asking them to coordinate some action in his name. I should also have added, for the many who replied with essentializing comments, that labels and affiliations won’t help. It is not about our theoretical inclinations, national belongings of sorts, political beliefs, or presumed associations.

Giulio was, in the words of his advisor in Egypt “steering clear of anything political”. He was aware and careful about it – putting him into boxes now that he cannot reply is not useful, even when made in good faith and affection.

The theorists we cite, the political inclination declared or assumed in our words, the groups we supposedly belong or should belong to, are unnecessary divisions in moments like this. We are researchers, that’s what brings us together. Our work contributes to the betterment of the society, gives voice to the voiceless, makes us think to what is not easy to think. This is our role, for which we want to be respected.

We can be critical and think about it with the most abstract questions in mind. But it remains quite simple for me – that a researcher cannot be tortured and killed for doing her/his job.

Our Universities won’t take liability. Our states won’t sacrifice their economic agreements.

If we are an academic community, we should stand up as one. We should say it out aloud, that killing an academic for his research is not going under silence. A whole huge group of people will point fingers to whoever has done this, and to whoever will not do enough about this.

The most critical mind may say that this is another way to use Giulio’s death. I don’t think silence is an option, won’t honor him nor save the next Giulio.” (L. C.)

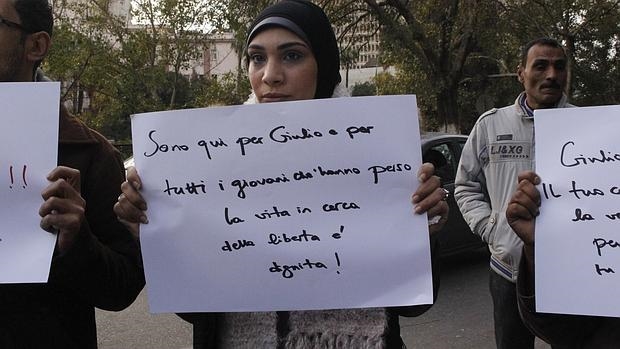

Activists protesting the murder of Giulio Regeni in front of the Italian embassy in Cairo on Saturday, Feb. 6, 2016. Source: dailynewsegypt.com.

Below we have tried to list some of the public statements, petitions and news reporting in response to Giulio Regeni’s murder.

A petition and open letter of protest over the death of Giulio Regeni, forced disappearances and torture in Egypt, initiated by Giulio’s supervisors at Cambridge, has attracted over 4600 signatories. It can be signed here.

The Middle East Studies Association of North America has reacted with a letter to the Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al Sisi, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Sameh Shoukry, and the Minister of the Interior, Major General Magdy Abdul Ghaffar, published on 4 February 2016.

An invitation to sign an open letter to the Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, to be considered morally responsible together with most Western countries for de facto supporting El Sisi, has been published here.

An event to commemorate Giulio’s life, as well as all other Egyptian students who daily risk their life for the freedom of speech, and to urge our governments to put pressure to get the truth has been organized for today, Wednesday 9 February, 5pm, at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Additional articles on the murder of Giulio Regeni have been published by the Guardian, the New York Times, Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian) and La Stampa (in Italian) amongst others. The latter has published some terrifying declarations of witnesses, which reveal not only the brutality of the torture, but also indicating that, if more pressure was exercised quickly, Giulio Regeni could, maybe, have been saved.

4 Comments