García-Lamarca reviews Gould and Lewis’s new book and highlights three missing and important topics for future research on green gentrification.

Does greening whiten? Does greening richen? Does greening raise rents and housing prices? These are the three core questions behind Kenneth A. Gould and Tammy L. Lewis’s new book titled Green Gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Gould and Lewis unpack five cases of greening in Brooklyn and illustrate how outcomes are often positive for environmentally sustainability but are socially unsustainable. They propose green gentrification as a process that creates and reinforces environmental privilege for elites in the city.

Gowanus canal: “from open sewer to the Venice of Brooklyn” (Gould and Lewis 2017, 86)

Taking a sociological approach to environmental justice, inspired by the work of David Pellow, Julie Sze and Lisa Sun-Hee Park, the authors use data from field observations, media accounts and the census to trace each Brooklyn-based case historically to its current status. This is by far the richest and most interesting part of the book. Particularly insightful are the cases where neighbors organized to contest green gentrification and make demands for social equity. Residents living around the Sunset Park waterfront redevelopment who were previously mobilized made more gains such as maintaining affordable housing and retaining the working class industrial waterfront character. This contrasts with the restoration of Prospect Park, where the populations in most surrounding neighborhoods whitened and richened. Here, community mobilization came too late in the process to ensure more structural responses to neighborhood affordability (zoning changes, affordable housing). The creation of Brooklyn Bridge Park instigated what Gould and Lewis term hyper-super-gentrification, as Brooklyn Heights was already wealthy, white and educated; the new park and multi-million dollar luxury housing located in it is exacerbating this trend.

Brooklyn Bridge Park. Source: NYC Photography

Overall, the book makes a valuable contribution to a wave of environmental justice (EJ) research that has emerged since the 2000s. This new strand considers how efforts to improve the environment can increase racial, income and other forms of inequity, shifting from EJ’s traditional focus on how environmental “bads” like landfills, toxics and other locally unwanted land uses disproportionately affect minorities and low income people. There are not only distributional justice questions at stake here (where environmental “goods” and “bads” are sited) but also questions of justice that relate to procedure (how decision-making and participation meaningfully occurs), recognition (acknowledging and respecting others) and capabilities (being capable of achieving the kind of life one values).

At the same time, I missed three important elements in Green Gentrification that I want to address and put forth as provocations to be unpacked in future studies in this emerging field.

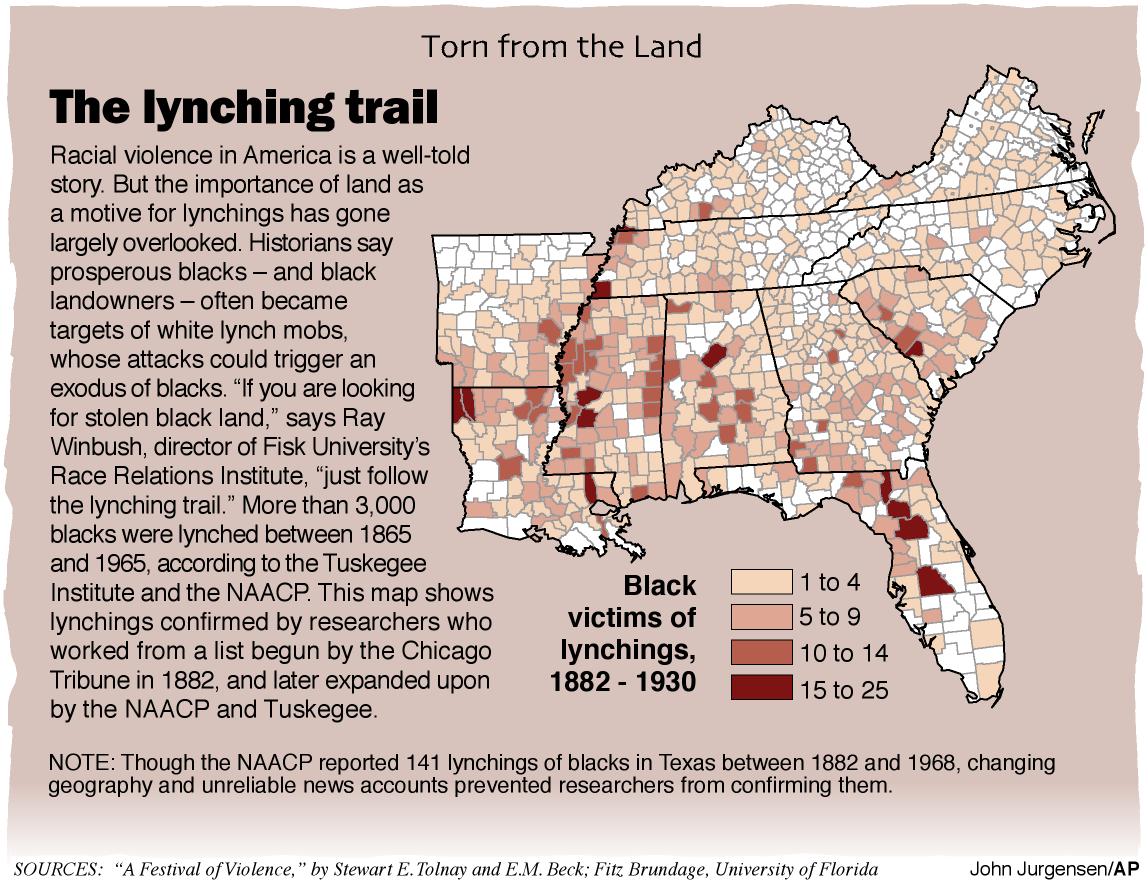

The first is the unquestioned, normative idea that “green is good” which underlies this book and most approaches to urban greening. Moving beyond the standard ecological and health arguments for the positive benefits of developing green spaces, I think it is critical to recognize the racial and class dynamics underlying creation of green spaces historically through to present. Parks, for example, have historically functioned as spaces to discipline working-class and racialized bodies, as Jason Byrne and Jennifer Wolch, among others, explain. In Black Faces, White Spaces, Carolyn Finney makes powerful statements about African Americans’ painful historical relationship to woods and parks as sites of lynching. The legitimate fear of these places serve as a “specific reminder that there are many places a black person should not go” (p. 60). Finney argues that this history can still limit the spatial mobility of African Americans due to a lingering concern for their safety while crossing predominantly “white” territory. Gould and Lewis associate green gentrification with an influx of whites into greened neighborhoods, but the analysis needs to go deeper. Recognizing that green is not inherently “good” for all and thinking through what that means for greenspace creation today is important in considering processes of green gentrification.

Woods and parks were often sites of lynchings of African American people in the US; writers like Finney speak of how this painful historical reality influences relationships with greenspaces today. Source: The Authentic Voice

Second is a deeper focus on the role of financial-sector investors and their rent-seeking strategies in processes of green gentrification. Gould and Lewis propose that green growth coalitions – where greening forms the basis for developers to lobby/manipulate local government to approve green urban (re)development – function through the logic of an urban greening treadmill. This framing draws off the treadmill of production theory, where economic growth is understood to be of general societal interest but that the response to the social problems generated by growth is more growth – and the resulting economic benefits are distributed upwards while environmental hazards are distributed downwards. In recent decades a new class of financial-sector investors have emerged – private equity investors or investment trusts for example – not only to capture this upward distribution of benefits but also as important actors driving speculative urban (greening) practices. A deeper look at these actors along, for example, the lines of Sarah Knuth’s research in San Francisco is important to unpack the various motivations, imaginaries and impacts of the role of financial capital in greening.

Related to this last point, my third and final comment is on the need for green gentrification research to stretch or extend the idea of how we understand the urban, in terms of processes, dynamics and actors. This ties to the emerging research agenda of planetary urbanization, a concept that recognizes the intimate connection between the urban and non-urban and thus the need to research urbanization as a process that occurs within and beyond the city. Green gentrification is thus not only a process that creates and reinforces environmental privilege for elites in the city, as Gould and Lewis state, but also for international elites (real estate developers, etc.). Furthermore, green gentrification occurs at the expense of the ecological and social destruction of other territories. In other words, the creation of environmental amenities in certain spaces is possible thanks to shifting “dirty” production and unwanted land uses elsewhere, be it to “peripheral” urban spaces in the same region or to various sites in the Global South. Operationalizing this thinking in practice is of course no small feat, but researchers at the Urban Theory Lab and elsewhere are testing methods to understand how these planetary processes of urbanization are unfolding.

Intimate urban-rural interconnections. Source: CITY

In closing, Green Gentrification makes an important contribution to this relatively new and emerging field, a field which is still under development. This brief review points to just a few of many areas that are ripe for further research.

One Comment