By Prakash Kashwan*

Democracies can do better than to give into the mirage of “Wilsonian Enclosures”, which envision half of the planet or more in nature reserves. The excessive focus on such areas detracts attention from developing alternative conservation strategies.

Renowned biologist E.O. Wilson advocates setting aside “half the planet in reserve, or more” exclusively for the goal of nature conservation. There can be no doubt about the need to counter the ongoing assault on earth’s ecosystems. In my two decades of engagements with natural resource management and conservation, I have worked on and studied various aspects of the intersection of conservation, local development and community rights.

In this blog I refer to my research about cross-national variations in the designation of protected areas to draw attention to one of the several fundamental flaws in the proposals for a massive network of exclusionary protected areas, which I name the “Wilsonian enclosures” (to place E.O. Wilson’s proposal within the context of the British enclosures).

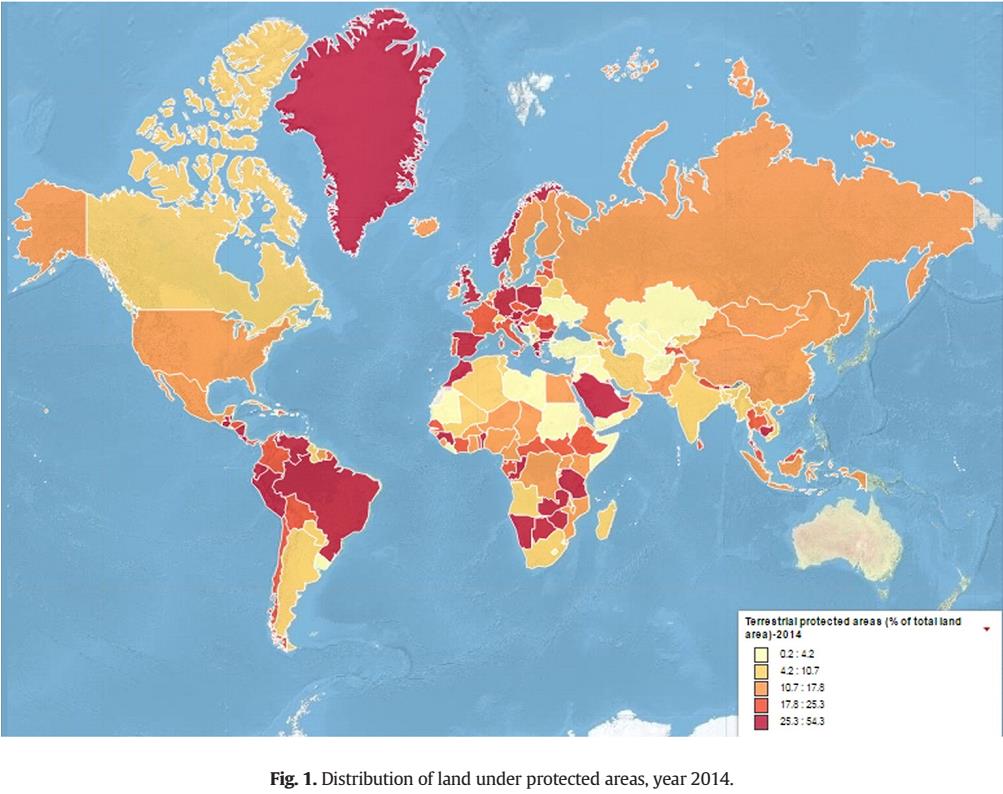

The overwhelming focus on setting aside ever larger areas as protected areas hides a puzzling trend in international conservation. Globally, the area of land set aside as protected areas nearly doubled between 1980 and 2000 (8.7 to 16.1 million square kilometers) and increased four-fold to 32 million square kilometers by 2014. The global protected area targets agreed on at the World Parks Congress meetings since the late 1980s have often been met ahead of the target years.

More importantly, despite the rapid economic growth in some of the largest forested countries since 1990, followed by the tumultuous recession of the past decade and a half, most countries in the world have seen significant increases, while none has witnessed a net reduction of the area under protection. What explains such significant and consistent expansion of protected areas globally?

Map of percentage of land under protected areas by country (lighter colors reflect lower % of total national land area under protected area status). Source: Kashwan, P. (2017) Inequality, Democracy and the Environment. Ecological Economics, 131.

In new research published in Ecological Economics, I use a global dataset of protected area designation in 135 countries to analyze the effect that political and economic factors have on the variation in the percentage of national territory that governments set aside as protected areas. The statistical analysis does not address the questions of, say, the historical conflicts between American Indians and the National park service, or the colonial legacies of nature preservation in the developing countries, though such histories do inform my arguments. The statistical analysis is based on contemporary data on democracy, inequality, and protected areas, while accounting for other relevant variables, which could affect the relationship between these variables.

The results of this research show that the rather unexpected expansion of protected areas is a product of political and economic inequalities, which interact in rather counter-intuitive ways: In relatively democratic countries, greater economic inequality is associated with a lower percentage of national territory set aside for protected areas, whereas in relatively undemocratic countries the reverse is true.

At low levels of income inequality, democracy is associated with a positive effect on the percentage of national territory set aside as protected areas. However, the democratic dividend diminishes consistently with increasing income inequality. Democratic countries with relatively greater economic inequality find it harder to set aside land for protection, as compared to their counterparts with lower levels of economic inequality.

On the other hand, quite surprisingly, in countries with poor democratic institutions, a relatively higher level of economic inequality is associated with a larger percentage of territory set aside as protected areas. The explanation for this puzzling outcome has to do with how protected area designation works in developing countries.

In countries with poor democratic institutions and high levels of inequality, governments can afford to bulldoze over the forest and land rights of indigenous and other forest-dependent people, who have customarily used these lands. Researchers at the ESRC STEPS Centre of the Institute of Development Studies, Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI), and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) refer to the phenomenon of locking away land and natural resources in the name of environmental protections as “green grabbing”.

But, don’t the conflicts triggered by green grabbing undermine efforts to designate protected areas?

They need not. Because of the failure of democratic institutions and lack of political accountability, many governments can afford to overlook these conflicts without facing political consequences. So why do politicians from developing countries care so much about protected areas?

India’s indigenous people, Adivasis, and local activists celebrate the 2006 Forest Rights Act, which recognizes household land rights and collective forest rights. Photo: Prakash Kashwan.

To answer this question, I synthesize a vast amount of research on policies and programs of nature conservation in the global South, which shows that setting aside protected areas often serves a number of political and economic interests for politicians.

First, heads of states contribute to internationally set protected area targets to earn the goodwill of the international community, which they can deploy to deflect political criticism. For the sake of illustration, consider the 1988 Mexican Presidential election leading to a tainted victory for Carlos Salinas de Gortari, or Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s suspension of the constitution (1975-1977), which led to gross human rights abuses. As documented in the studies hyperlinked above, each of these world leaders exploited wildlife conservation as a public relations tool.

Secondly, protected areas attract international funding, further reinforcing the authority and punitive powers that government forestry and wildlife agencies derive from colonial-era laws, which continue to be in practice to this date in many countries.

Third, in many cases, international conservation funds often feed the rent-seeking networks led by corrupt government officials and political leaders, even as the foot soldiers of wildlife conservation remain underpaid.

Lastly, protected areas also enable governments to control extractive activities and give them an edge in their fight against political insurgencies. Recently, scholars have examined instances of war by conservation in which “global security concerns, specifically the US-led War on Terror and Counterinsurgency” seem to be the primary goal while “conservation is relegated to a position of secondary importance.”

If protected areas are merely an instrument, which national elites use to exploit international support for wildlife conservation, it is unlikely to lead to effective protection in the long run. Evidence from “gap analysis” studies I cite in the Ecological Economics article lends support to such concerns.

More importantly, as I show in another article in Regional Environmental Change, a narrow focus on bringing increasing areas of land under protected area regime detracts international conservation groups and national wildlife agencies from developing alternative strategies, including in the context of large-scale landscape conservation initiatives supposed to take care of the limitations of protected area-based conservation.

Taken together, a reliance on the easy task of legal designation of protected areas, in the hope that such areas will be brought under effective conservation at a future date explains why, despite the significant expansion of protected area networks, the world has witnessed “catastrophic declines in wilderness areas over the last 20 years.”

Wildlife thrives in the central Indian grasslands, which are a product of generations of interventions by indigenous and other peasant groups. In the picture: Rajbehra cubs in Bandhavgarh National Park, one of the most popular in India, located in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Photo: Ashish Tirkey.

These findings point to an important flaw in the logic that informs proposals for significant expansion of the protected area network. E.O. Wilson argues, for instance, that the “psychological argument for protecting half of Earth” is that the “current conservation movement has not been able to go the distance because it is a process.”

In reality, protected area-based international conservation is a target-driven enterprise. The target of bringing 17% of the earth’s territory under protected areas, which many argue should be increased further, is the single most important signifier of the success of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity.

Departing from the currently popular target-oriented models to process-oriented approaches to nature conservation would indeed be preferable, as long as the process is geared to facilitate democratic deliberations and careful prioritization of conservation strategies. Such processes should distribute the costs of conservation equally among, say, Montana cattle ranchers, Australian wheat growers, (and) Florida retirees, while fairly compensating the indigenous people in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, who in the past have received little more than the rhetoric of rights-based approaches to international conservation.

While it is important to articulate these issues, how should policymakers think about a potential transition out of the current approaches to conservation that are rooted in forest policies of the colonial era and exploit contemporary political and economic inequalities in developing countries?

The efforts of international conservation groups to engage non-state actors, such as indigenous groups, are laudable. Even so, bringing indigenous people into advisory bodies does little to change the big forces that are driving the siting of protected areas in lands that belong to politically marginalized indigenous and other forest-dependent groups. This is so because the policymaking related to protected areas is controlled by political elites and government ministries.

Popular protests against the designation of protected areas are rarely successful. Conservation social scientists and activists committed to “just conservation” continue to catalog numerous instances of the violation of the rights of forest-dependent people. Popular concerns are bulldozed with such impunity, I argue, because of the manner in which conservation’s perverse incentives interlock with domestic political economic inequalities.

The most important task for international conservation agencies, arguably, is to not support, or withdraw support from, national ministries and wildlife agencies unless they cease the routine violation of forest and land rights of forest peoples. National ministries could also be mandated to accord statutory recognition to the alternative models of socially just conservation, such as Indigenous peoples’ and community conserved territories and areas (ICCAs) recognized by the IUCN.

More importantly, while ensuring proper regulation of nature tourism and ecotourism, governments could be required to set up internationally verifiable accounting procedures to ensure that a sizeable share of conservation related incomes is transferred to local communities. When park administrations permit eco-tourism operators and hoteliers to profit from mindless exploitation of natural resources within and in close proximity to protected areas, it greatly undermines the credibility of international conservation.

Wildlife and eco-toursim operations must be managed responsibly. In this picture: Golden Jackals being observed by tourists. Photo: Ashish Tirkey.

The argument above about the legitimacy of international conservation relates to another prominent critique of the Wilsonian enclosures, which are by no means a radical proposition. How does one justify taking vast swaths of earth’s territory out of food production and potentially condemn the world’s poorest people to hunger (as witnessed during the biofuel boom), while a section of humanity revels in wasteful consumption of all sorts?

Wilsonian enclosures are an effort to compensate for our collective failures by forcing protected areas on the populations, which are too poor and politically marginalized to secure a dignified life. A more radical proposition would be to change our lifestyles and to wage a fight to ensure that our governments do not facilitate wasteful plunder of natural resources.

While ensuring the participation of indigenous and other forest-dependent people is important, such participation cannot be a substitute for the accountability of the prime movers of “big conservation” – the political and economic elites in developed and developing countries, large corporations, international conservation groups, and national forestry and wildlife agencies.

* Prakash Kashwan is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Connecticut, Storrs. His first book “Democracy in the Woods: Environmental Conservation and Social Justice in India, Tanzania, and Mexico” will be released by Oxford University Press in January 2017. A shorter version of this blog was published on the Washington Post blog MonkeyCage and a crisp summary is available at Conservation Watch.

This is a great post. The paradoxes and shortfalls of the Wilsonian “fortress parks” are talked about often in my graduate program, and it’s good to hear someone outside of our fairly radical group discussing them as well. There’s a reason why global conservation is largely failing, despite the increase in protected areas; besides the oft-used argument of overpopulation.

Thank you — a long term goal is to develop a sort of a “realist radicalism” if one could think of something like that. I develop this further in the forthcoming OUP monograph hyperlinked as part of the byline.

Thank you for this piece Prakash, very interesting and very important. I would be interested in reading more about what your conception of ‘realist radicalism’. It is also a position I am attempting to pursue.

Cathel, Thank you for your engagement. I look forward to exchange notes about this. Since I can’t see your email ID here, would you mind emailing me your contact details at prakashDOTkashwanATuconnDOTedu?