by Cristóbal Bonelli

With the notion of heterotopia Foucault describes spaces that are somehow “different”, mirroring and yet distinguishing themselves from what is outside, like gardens, cemeteries, or ships. Heterotopias are places of imagination, escape, otherness and a microcosm of different environments. Cristobal Bonelli found his own heterotopia in the IHE library, during the presentation of the book “Water, Technology and the Nation-State”.

As it happens, reading books is an exercise that reminds us of previous readings, previous books; reading triggers different memories, it entails a silent and intimate exercise in which we re-visit once again others’ ideas, authors and presences that have already inhabited our worlds in different times of our existential paths. To put it differently: a reader is a shaman crossing borders, capable of entering into different worlds; and, as it happens, shamans are forbidden in the realm of Capitalism: as witches of golden times, good readers are today the target of persecution. Because reading entails time, and time, as the story goes, is money. So, read less and work more, an unwelcomed imaginary colleague whispers in my ear while I write this text. Reading a book is becoming an utopia, a no-place-no-time impossible endeavor.

Yet, what to do about it? My colleague and new friend Emanuele Fantini offered me an answer. When he invited me to read and comment on the book ‘Water, technology and the nation-state’, edited by Filippo Menga and Erik Swyngedouw, I first said: I do not have time, as I was going through a very stressful grant proposal writing period, and, as a good hunter of money, I thought I did not have time for reading a book. But then I rethought about my automatic-robotic reaction, and I am happy to have done so, as I did not know that that reading was going to refresh a very powerful joke I have already read in two different books along my reader-journey. More importantly, I did not know that reading that book was going to be an unexpected entrance towards the possibility of having access to a heterotopia within IHE’s library. As Michel Foucault (1984) wrote about heterotopias:

‘First there are the utopias. Utopias are sites with no real place. They are sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces. There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places — places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society — which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted’.

I did not know on that day that the invitation by Emanuele would have turned to be an invitation towards an experience of the IHE library as heterotopia.

But let’s start by telling the joke the book reminded me of, which was a well-known joke set just after the Second World War. Let’s use it as a sort of pretext for shedding light on one of the many concerns upon which, I think, the book at stake is predicated.

It was at one of the Macy conferences, a set of meetings of scholars from various disciplines held in New York (1941-1960) that aimed to promote meaningful communication across scientific disciplines, where the anthropologist Gregory Bateson (1953) used this joke in order to explain some basic principles of human communication, in general, and human humour dynamics, in particular:

‘A worker of a factory carries out a wheelbarrow with plenty of rubbish every time he leaves his job. The guard of the main factory entrance notices this daily behaviour and starts to think that the worker is stealing something, which may be hidden in to the wheelbarrow. Despite the fact that he looks daily for some evidence among the garbage, the guard does not find anything. Nevertheless, his suspicion remains and one day he speaks bluntly to the worker: ‘Come on John, just tell me what you are doing with all this garbage. I thought that you were stealing something, but I have not been able to find out what you are doing, just tell me what are you doing, otherwise I will be forced to add your name to the list of suspicious people’. The worker replies: ‘Ok, maybe we both could make a living by sharing the several wheelbarrows I already have at home’.

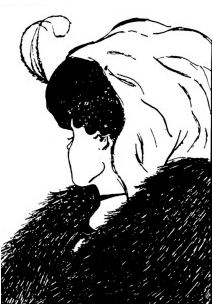

Gestalt theories were well known by Bateson. By telling this joke he wanted to point out not only the natural capacity of human cognition to perceive either figure or background -never both at the same time- but also the paradoxes that are naturally built over this figure-background tension: the background is part of the implicit information and cannot be avoided, it is inevitable information.

Bateson’s point was that the background remains totally invisible but always present when we give a name to some object or action. The young lady disappears when we foreground the old woman. Although Bateson was trying to point out how human humour works and what makes us laugh, his main attempt was to understand how, broadly conceived, human communication occurs. He concluded by saying that, following Russell’s well-known paradox about a set that qualifies as a member of itself, we are always trapped in linguistic paradoxes. This contradicts the set itself defined as a set containing sets that are not members of themselves, or, for instance, ‘Christ was not Christian’ or ‘Freud was not Freudian’ (Wheelwright, 1959), or more importantly for my comment on the book, and as I will show later on, water technological fixes (the garbage of our joke) are not part of the political background affording such fixes (the wheelbarow).

What do you see in this picture? An elegant young lady, or an elderly one?

The Marxist sociologist Slavoj Zizek was three years old when Bateson was telling this joke at the Macy Conferences. Although sixty seven years have passed ever since, Zizek himself starts his book ‘Violence’ (2009) by telling us the same joke, even if he refers to it as an ‘old story’ instead as a ‘joke’, probably because within his reflection there is nothing to laugh at. Most of the time within our Capitalist world, Zizek argues, we cannot see what is apparent because it remains in the background. He claims that there is a sort of produced blindness in our way of perceiving the world, a ‘generative matrix that regulates the relationship between visible and non-visible, between imaginable and non-imaginable’. (Zizek, 1994 :1). Broadly conceived, and by using a Lacanian lexicon, Zizek points out that there are two different orders regulated by ideology, namely, the explicit manifestation of knowledge (the Lacanian Symbolic domain) and a more unrepresentable ‘appearance beyond appearance’ (The Lacanian Real domain), the ‘inexorable abstract, spectral logic of capital that determines what goes on in social reality’ (2009:11).

This generative matrix is ideology, and he strongly urges ‘keeping the critique of ideology alive’ (1994:13) in a world that tends to find a ‘slick postmodern solution’ (1994:17) to social problems and inequalities. In other words, what Zizek is saying is that we cannot see the wheelbarrows as long as we cannot see how ideology works. Totalitarian systems and neoliberal systems would share this particular mechanism of rendering invisible their own way of functioning. When analysing violence, Zizek claims that there is something symptomatic in mainly focusing on ‘subjective violence’ (violence performed by a clear identifiable agent) as this ‘is just the most visible portion of a triumvirate that also include two objective kinds of violence’ (2009:1): ‘Symbolic violence’, embodied in language that implies an ‘imposition of certain universes of meaning’, and ‘Systemic or Objective violence’, violence inherent in a system (2009:1). The main thesis of the author is that ‘subjective violence’ is experienced as such against the background of a non-violent zero level. It is seen as a perturbation of the normal, peaceful state of things. However, objective violence is precisely the violence inherent to this ‘normal’ state of things’ (2009:2), inherent to the pervasive invisible ‘abnormality of the normal’ (Scheper Hughes, 1992:187). The ‘non-violent zero level’ is possible because of ideological regulations and it should not be thought as a taken-for-granted social dimension, even if it appears as the wheelbarrow of our old story.

I think the book ‘Water, Technology and the Nation-state’ keeps the critique of ideology alive. One of the ways it does so is by mobilizing a non-commonsensical use of the term ‘technology’; or at least, an understanding of technology that would not be immediately clear for a water natural scientist. Responding to Gramsci’s call to replace common sense by good sense, the book presents the ‘nation-state’ as a political technology understood as a process and fluid entity, as a ‘heterogeneous assemblage of social grouping, political actors, and economic forces useful to understand the intricate and intangible web of relationships that play a crucial role in the appropriation, dispossession, and distribution of water resources’.

Embracing the project of Political Ecology, the book deals with water as always entailing a dramatic exercise of power articulated through material things. Water, for this approach, is always, and at once, social and material: it is always a political entity. This explain why different chapters deal with ‘water’ through what might be considered, from the point of view of water hydraulic-technicians, to be an ‘elusive rhetoric’: they do not deal explicitly with H20. Indeed, the problem for many of the chapters is not H2O, but political power. However, while this premise has become common sense among political ecologists, this has not been necessarily the case for water professionals. And this is why the joke by Bateson and Zizek came to my mind while reading the book. And this is why my comment of the book that day was simply to put together two very different uses of the term ‘technology’, the one implied in water ‘technological fixes’, and the other one mobilized by the book through the idea of the nation-state as a ‘political technology’.

The illusion that water problems and conflicts can be indeed ‘solved by having more water’ is alive, particularly within economic transactions that tend to remain obscure for citizens who count their pennies to make a living.

Examples abound: I leave up to the reader to think about them.

What I want to say, and what the book reminded of, is that technological fixes can be seen as the garbage of our joke. As a figure, technological fixes make invisible a political, historical background from which many water conflicts emerge. As an unquestionable figure, technological fixes authorize the rules of the game of capitalistic logics, affording good business transactions (and the so mysteriously called win-win situations!!?) between people owning expensive knowledges and technologies, and other people willing to own those knowledges and technologies in order to improve productivity (within the water sector and beyond). Examples abound, and I was being existentially bothered by few related examples stemming from my own fieldwork while I read the book.

If you make time for reading, perhaps you will agree with me that the book creates public awareness about how good governance does not depend on technological fixes, but rather depends on bearing in mind, and acting upon, the unevenly distributed increasing entanglements of peoples, water and materials. In this respect, the book can be seen as motion against Ideology in water conflicts. And in this respect, I am closer to Zizek’s understanding of the joke as an ‘old story’, rather than a proper joke, as there is nothing to laugh about. The ideology of water conflicts that builds upon the idea that more water will solve problems needs to be undone daily in our practices. Thinking that technological fixes are enough for solving problems forces us to deal with the problem of violence and agency within water debates, and subsequently the question of the localization of violence becomes crucial: how can we visualize, and how are water experts practically visualizing, the agent of violence in order to respond to it and to really treat water as a political subject? Without saying it explicitly, the book reminds us that a way to do that is by following a sort of Foucaultian ethic imperative, namely, that the role of intellectuals is ‘to question over and over again what is postulated as self-evident, to disturb people’s mental habits’ (Foucault 1982:349).

I did not know that reading this book was going to be an unexpected entrance towards the possibility of having access to a heterotopia within IHE’s library, an invitation to experience the library as being something like a counter-site, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Inhabiting the library with others as a space for thinking and togetherness demanded effort and time. If there is something that a book demands too is to ‘slow down’ reasoning, to put it with Isabelle Stengers famous call, and that day the library of IHE afforded that exercise to come into existence.

Reading is resistance too, which on a good day as the one organized by Emanuele, can reveal how water issues are not post-political issues, as if water professionals would have left behind old ideological struggles and, instead, focus on expert management and administration. The de-politicization of water issues emerges as the dangerous wheelbarrow that no one notices and forces us to look daily for some technological fix among the Other’s rubbish. The book can be seen as a reversion of this joke. And there is nothing to laugh at.

(Thanks to Andrés Cabrera for having checked my English)

This post has been originally published in FLOWs, the water governance blog at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education

Cristóbal Bonelli is a Marie Curie Senior Researcher trained at the intersections of science and technology studies, social anthropology and clinical psychology. He holds a PhD from the University of Edinburgh. His research explores socio-natural entanglements and clashes between scientific and indigenous worlds and practices. He joined the Water Governance group at IHE Delft to study interactions between people and groundwater in one of the driest places on earth: the Atacama desert of Northern Chile. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 706346

Reblogged this on POLLEN.