By Emma Li Johansson*

Art in research is a powerful tool to evoke feelings and actions beyond academia. This researcher set out to see what is possible when mixing research with artistic ways of expression.

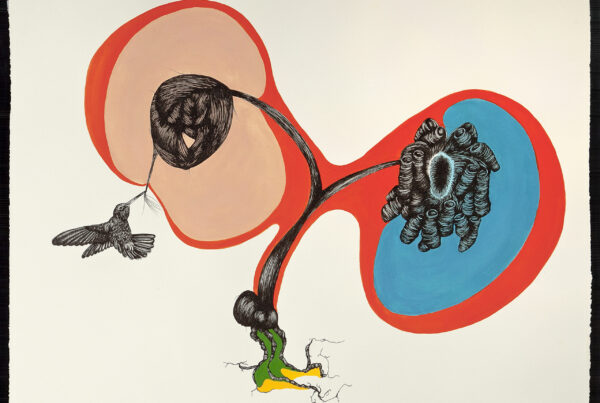

Figure 1. Painting of the future, which shows the aspirations of the youth: improved infrastructure, better natural resource management, and increased participation and influence over company decisions. Source: Emma Li Johansson, 2015.

A picture says more than a thousand words, they say. Which is why art is a good way to inform people about urgent issues, like environmental degradation and social inequalities, especially in these busy times when few have the patience to read a thousand words. Art is also more appealing to a wider audience, and might be easier to understand than a complicated scientific text.

What frustrates me the most of learning about social struggles in rapidly changing environments is that we keep preaching to the choir. We stay within our safe ‘academic bubble’ and keep talking to people who already know about these issues. This is of course also important, but we need to find ways to inform people outside the bubble, and I think art has the potential to do that.

The idea to use art in my research about socio-environmental effects of land use change (in the context of land grabbing) grew from my own experience as a painter. Some years ago, I casually met Joseph Mwalyombo, an artist, in Dar Es Salaam (Tanzania) and we started to paint together. He taught me the local art style ‘tinga-tinga’, and I visualized my perceptions of how land grabbing affects people and the environment. That’s why I decided to go back to Tanzania and make such paintings with people affected by large-scale land-use changes.

Land grabbing in Kilombero Valley

The fieldwork took place in the wetland area Kilombero Valley, a biodiversity hot-spot with suitable climate for rice and sugarcane cultivation (Figure 2). The whole valley has been experiencing high pressures on farmland and natural resources during the last decade due to rapid population growth and migration of pastoralist groups (Kangalawe & Liwenga 2005); and from domestic and transnational interests to either protect the land or convert it to large-scale production units of rice, teak and sugarcane.

The paintings were made in two villages: one that is leasing land to Kilombero Plantations Limited (KPL), a company which produces rice, and another village that is leasing land to Kilombero Valley Teak Company (KVTC), a company which produces teak. In both villages the community members are engaged in agriculture – growing mainly rice, but also maize, bananas, and palm oil – fishing and pastoralism, and are heavily dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods.

Figure 2. Man biking through the Company Rice plantation. The village land stretches from the Kilombero River wetlands in the south to the Udzungwa Mountains in the north. Source: Emma Li Johansson, 2015.

The 99-year land leases have led to much dissatisfaction in the affected communities, and in some cases have created conflicts over societal and environmental change. In both villages, farming has become more challenging as more people now share less land. Few community members see any benefits from the presence of the company, since employment is seasonal, labour-intensive, and poorly paid. Local communities also experience little power over land-lease decisions, since the Government is the ultimate custodian of the land.

I use art in my research to help raise the voices of community members whose livelihoods are being affected by the foreign agribusinesses but are often disregarded in the land-grabbing debate.

HOW to paint land grabbing?

In order to get an overview of how the communities use natural resources, how they experience environmental change, and what are the reasons for change, I held several focus group discussions. At the end of the sessions I introduced the participants to the idea of visualizing their perceptions as paintings of the past, present and future.

At first, no one wanted to participate for the simple reason that they had never painted before. However, some people changed their mind when I explained that Joseph Mwalyombo would instruct them, and that we would make the paintings together.

We began with the painting representing the current situation, which formed the baseline for visualizing the past and future. This painting was the most challenging since the participants thought I wanted to map out all houses, roads, and streams at their exact locations. I had to intervene and explain that I wanted a picture of the village and village activities from a bird’s perspective – far enough to see the different parts of the village, but close enough to see what people are doing.

Joseph started to sketch on a piece of paper, and the participants told him where the mountains, rivers, settlements, company area and roads are located in relation to each other (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Participants explain to the artist Joseph Mwalyombowhere roads, settlements, rivers, mountains, company areas, wetlands, and village farm fields are located in relation to one another. Source: Emma Li Johansson, 2015.

Joseph transferred the sketch to the canvas, and the participants were taught how to hold the brush and how to make strokes of colour on the canvas. Their confidence gradually built up by starting with the easy tasks and then advancing.

The paintings are made layer-by-layer, starting with the background and thereafter adding more details (Figure 4). The oil based ‘bike paint’ thinned with gasoline (I know, not so environmentally friendly, but that’s how it’s done) dries fairly quickly, so the layers could be added without much wait.

Figure 4. The painting technique of tinga-tinga consists of making layers on layers, adding more details in each layer. Source: Emma Li Johansson, 2015.

The first challenge of painting the past was to decide which past to depict. We decided to focus on the time just before the arrival of the companies (10 years in one village, 30 in the other). Now the population, settlements, forests and rivers could be resized and replaced in relation to the current situation, to show increases or decreases, improvements or degradation.

In both villages, the paintings of the past and present point to environmental changes including deforestation, decreased water levels in rivers, reduced wildlife, and less land available for farming (Figure 5). The presence of the companies has had both direct and indirect effects on natural resources. Direct effects include reduced water levels in rivers due to irrigation or introduction of tree species with high water requirements, while indirect effects are manifested in deforestation and lower fish stocks in the rivers, because people have lost access to land where they used to farm (causing them to shift to fishing) and fetch firewood.

Finally, we made a painting of future aspirations (Figure 1). This was a challenge in itself since it was impossible to capture everyone’s future aspiration. It was easy to reach consensus when describing the past and present situation, but for the future the opinions differed between young and old, women and men, farmers and pastoralists.

Nonetheless, the future paintings show the aspirations for increased influence and participation in company decisions (represented by people meeting under a mango tree), which affect their common resources. And if the company should stay, the local community should be able to benefit from their presence.

Figure 5. Two of the paintings representing the past and present socio-environmental situation. Changes in the environment include reduced forest cover, lower water level in rivers, reduced number of fish and wildlife. Source: Emma Li Johansson 2015.

During the painting workshop many people passed by to see what we were doing. Which was good since there were only two participants per painting, and it showed me if what had been depicted agreed with their perceptions as well. People often gathered around the paintings to point out what stories they could identify, such as the airplane spraying fertilizers on the company fields and affecting the water in the wells and rivers, which in turn causes health problems for both people and animals (Figure 5, painting to the right).

The three paintings took about 10 days to finish, which gave me time to talk to people passing by and get familiar with the surrounding area. For me it is important to not just come to a community and extract information over a day, but to build trust and relationships over time. I also wanted to contribute with a creative experience that formed a product that the community could keep for the future. I think this type of ‘mini-ethnography’ approach is a good way to de-colonize research and to engage people in co-creating a participatory product.

The power of art in research

The ultimate goal of using art in research is to spread the information to a wide audience, as an alternative to the more common article format. Earlier this year I managed to arrange an exhibition with the National Museum and House of Culture of Tanzania, in Dar Es Salaam. The exhibition was covered by the media (Figure 6), and people with different backgrounds came to visit the opening event – researchers, students, NGO workers, politicians, tourists and other visitors.

Figure 6. The art exhibition and research project covered in the Daily News, Tanzania, on March 4, 2016.

Although our initial idea for the exhibition was to have discussions among different stakeholders about the socio-environmental issues related to land-use change and land grabbing, we had to change the plan. The day before the opening event, we realized that people (including myself) could get into trouble for talking too openly about this politically sensitive issue. Thus words like large-scale land acquisitions, empowerment of small-scale farmers, foreign agribusinesses and company names were removed from speeches and information sheets (Figure 7).

However, it is not that easy to censor a whole painting. The paintings speak for themselves, and even though many words could not be heard or read, everybody could still see the stories in the paintings.

With these last words I want to encourage researchers to use art in different forms for sharing your research outside of academia. Art is a powerful tool, and has the potential to evoke feelings and actions beyond academia. If change towards sustainability should happen, we need to get out of our academic comfort zone and see what is possible to achieve when we mix research with artistic ways of expression.

Figure 7. For the exhibition at the National Museum and House of Culture of Tanzania the company names had to be covered with white colour. Source: Emma Li Johansson, 2016.

For more information, keep your eyes open for the full article “Local perceptions of land use change: Using participatory art to reveal direct and indirect socio-environmental effects of land acquisitions in Kilombero Valley, Tanzania” (currently under revision at the Journal Ecology and Society).

* Emma Li Johansson is a PhD candidate at the Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, and part of Lund University Centre of Excellence for Integration of Social and Natural Dimensions of Sustainability. Her research is about drivers and effects of land use change in areas where land is acquired by foreign agribusinesses, focusing on how people are affecting – and are affected by – changes in land and water availability.

Reblogged this on .