by Jonah Wedekind

Bitter Lake by Adam Curtis puts Afghanistan at the centre of global struggles over ideology, politics, and economy. The film tells a simple story about the political ecology of chaos, complexity and crisis, and about how politicians have lost their ability to tell simple stories that simply make sense.

“Increasingly we live in a world where nothing makes any sense. Events come and go like the waves of a fever, leaving us confused and uncertain. Those in power tell stories to help us make sense of the complexity of reality, but those stories are increasingly unconvincing and hollow. This is a film about why those stories have stopped making sense. It is told through the prism of a country at the centre of the world: Afghanistan.” – Adam Curtis, Bitter Lake (2015).

It is a dialectical art for one to criticise mainstream simplifications of complex realities and chaotic crises, and to then proceed with telling a simple story that offers an alternative explanation of complexity or another way of looking at chaos. In his new film Bitter Lake, the BBC’s documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis shows that he is a master of this dialectical art. The big story of Bitter Lake is that in times of permanent crisis, when we are faced with what seems like a constant acceleration of chaotic news-events and continuous bombardment of confusing news-information, politicians have lost their confidence and ability to tell the public simple and convincing stories that make sense of all the chaos, complexity and crisis.

Adam Curtis’ previous documentary trilogy All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace argued that politicians had bought into an ideology (neoliberalism) which claims that societies should be more self-regulating and economy-driven, in order to be more like an ecosystem that provides natural stability. The trilogy shows how markets, assumingly controlled by machines and not by politicians easily corrupted by power, were increasingly allowed to run economies and societies since the 1970s. As the films also show, the contradiction of this neoliberal dream was that the global economy spun out of control and into a state of permanent crisis – a nightmare which the politicians ironically tried but failed to explain and regain control over.

Source: Adam Curtis, The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts (2011).

Bitter Lake builds on these ideas. The narrative of the film suggests that although western politicians still want to change the world, they fail to do so, because they have given away their power to market forces. Meanwhile, the public is overwhelmed by feverish waves of new events and an overflow of new information in the media. Having lost their power to markets and their voice to the media, politicians are also losing their confidence to simply tell and sell simple stories of good and evil that the public will easily buy into. Adam Curtis suggests that the eras when Reagan and Thatcher (Cold War) or Bush and Blair (War on Terror) could tell the public stories which neatly divided the world into good and evil in order to justify economic policies and military interventions, are over. The case Adam Curtis uses to make these points is Afghanistan.

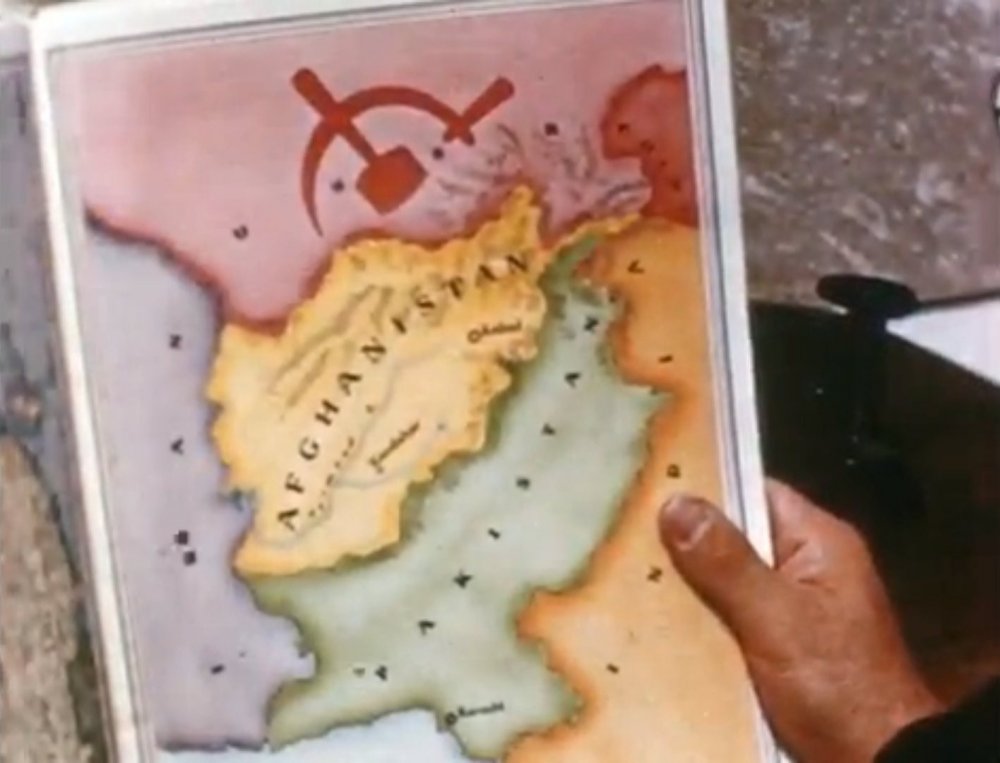

Seemingly a peripheral country, Afghanistan has been a battleground for proxy wars between strong global forces like Soviet Communism, US Imperialism and Saudi Wahhabism. But Bitter Lake breaks with simple divisions of the world-system into ‘core and periphery’ or ‘first world and third world’. The film convincingly places Afghanistan at the centre of the current chaotic crisis situation of the world-system and at the centre of world-historical struggles over ideological, political, economic and military influence. But which western politician today can still tell a simple, convincing story that explains and justifies past military interventions in (or current withdrawals from) Afghanistan?

The Great Game: Adam Curtis’s Bitter Lake. Source: bfi.org.uk

Afghanistan’s history seems too riddled with internal contradictions which are the ironic consequences of foreign involvements and invasions: From warlord warfare to the early formation of a modernist Afghan state backed by US development schemes. From the Saur revolution which brought forth a communist regime, to a Soviet war against Mujahideen warlords backed by Saudi Arabia. From the rise and rule of the Taliban and al-Qaeda, to the military invasion by the USA and its allies. From ongoing attempts by the International Security Assistance Force to install a technocratic government, to the brutal beginnings of the spread and influence of Islamic State seeking Sharia law.

At a nearly dizzying pace, Bitter Lake recounts the contradictions of Afghanistan’s history. The film took its name from a 1945 meeting between US President Roosevelt and the Saudi King Abdul Aziz on the Great Bitter Lake, a salt lake along the Suez Canal. The two leaders struck a deal according to which the USA could buy sufficient Saudi oil and would not interfere with Saudi Arabia’s spread of Wahhabism in the Middle East, including Afghanistan. The irony of the story being, that half a decade later the USA and its allies would have to invade Afghanistan to fight jihadist Islamic movements in Afghanistan which were initially influenced by Saudi Wahhabism.

Roosevelt and King Ibn Saud at the Bitter Lake meeting (1945). Source: theconversation.com

Beyond USA’s thirst for oil from Saudi Arabia, Adam Curtis is also attentive to the contradictions of the political ecology of US built irrigation dams in Afghanistan. In the manner of James C. Scott’s narrative on how schemes to improve the human condition have failed, the film reminds that the dams which the USA built for Afghanistan in the Helmand province turned out to be a massive ecological disaster with bitter side-effects. Instead of improving agricultural production for cotton and grain, the dams turned nearby rivers and irrigation canals salty, stimulating the growth of poppies which soon made Afghanistan the second largest exporter of heroin in the world. While much of the heroin money would be used by Mujahideen warlords to kick the Soviet forces out of Afghanistan, the heroin trade, although regarded as un-islamic, would eventually also fund the Taliban to resist the US and British forces. While Afghanistan’s wars seem to historically oscillate between holy wars and opium wars, today the heroin trade strengthens the political and economic power of former warlords who continue to undermine attempts by the USA to install a functioning technocratic government in Afghanistan.

Helmand Valley Authority, Afghanistan. Source: Adam Curtis, Bitter Lake (2015).

Bitter Lake traces the contradictions of the history of foreign interventions in Afghanistan with a collage of images and videos, many of which were unused material, shot for -or in between- news coverages of the Afghanistan wars and had been for a long time forgotten in the BBC’s archives. Watching Bitter Lake is a bit like watching “the waves of a fever” – at times “leaving us confused and uncertain”, so much that we get a “sense of the complexity of reality”. Overlaying the images is the narration by Adam Curtis, which weaves together a complex collage of images into a story that sounds so simple and clear. Of course his story of Afghanistan at the centre of the world is simplified and serves his own arguments. But rather than this being a contradiction, his story telling is a dialectical art. Unlike many western politicians, Adam Curtis finds the means to tell a big story. This one on Afghanistan is told in new and convincing ways and despite its visual chaos, it actually makes sense. It shows that the war on terrorism is a farce. There is a good reason behind this form of storytelling, one from which Political Ecologists can learn much:

All reality is incredibly complex and chaotic. To make sense of it we have to tell stories about it – which inevitably simplifies. And that is what politicians – and journalists – do. What I try to do is to find new facts and data, things you haven’t thought about, and turn them into new stories. My aim is to use those stories to try and make the complexity and chaos intelligible. – Adam Curtis (2015).